A question of complexity: challenging the myth of social mobility in the Neolithic

-

Research

- Culture and Communication

Posted on 15 June 2018

Research by archaeologists at York could challenge understanding of social mobility among some of our earliest ancestors.

A reconstructed early Neolithic longhouse from central Europe. These large timber-frame buildings characterise the architecture of the first farmers in Europe, and were around 20 meters long.

When doing this research in the past we’ve looked at the ‘elites’; wealthy people with rich graves, big houses and high cost monuments. What we’re able to do with bioarchaeology is look at burials of people who don’t have elaborate grave goods and tell their story for the first time.

Led by Dr Penny Bickle from our Department of Archaeology, the project, based along the Rhine river (Alsace, France), uses the latest radiocarbon dating techniques to track the development of society from the Neolithic to the dawn of the Roman Empire.

“There’s an accepted assumption that prehistoric societies became more complex as time went on,” says Dr Bickle. “So we think that people went from being hunter-gatherers, living in small groups and then settled down and began to farm, giving social complexity a clear, constant trajectory up until the beginning of the Roman empire.”

Challenge

But new archaeological techniques have cast doubt on this trajectory and Dr Bickle says her project will challenge those assumptions by looking at the beginning of the Neolithic period, about 7,500 to 4,500 years ago, in far greater detail than has been possible before.

She said: “Previous research into human mobility using strontium isotopes in teeth had shown us that certain grave relics were associated with a very narrow band of people. In order for that to be significant the living conditions in childhood had to be influencing what you were buried with at the time of your death.”

“Previously, we’d believed that status in childhood did not relate to status at death some 30 or 40 years later in adulthood. So to discover there was a sort of inheritance system taking place took us by surprise.”

Further research using Bayesian modeling radiocarbon dates meant the time period could be looked at in finer detail. Dr Bickle explained: “It allows us to analyse periods of time much more accurately. Without the technique we would look at broad periods of 200 - 300 years, we can now refine that to 25 years, sometimes less.

“That’s a revolution for human prehistory in terms of precision, but also the scale on which we can talk about change.”

Working in the Rhineland and focussing on a 1,000-year period in the early to mid-Neolithic, the new research threw up some totally unexpected results.

“Firstly, we found a gap of about 100 years where this area was completely depopulated,” says Dr Bickle. “We also found that some timeframes we had thought to be 200 - 300 years in duration were in fact as brief as 120 years.”

Intriguing

Dr Bickle said her research had left her with more intriguing questions to answer, hence the ‘Counter Culture’ project was born.

“The research is saying there isn’t a steady trajectory of simple to complex society.” says Dr Bickle. “In fact, we have an explosion of life which suddenly disappeared, and where we thought there were gradual transitions from one way of life to another in reality we have a 100-year ‘gap’, after which an entirely different way of life came along.”

Strontium isotopes, Bayesian radiocarbon dating and dental calculus techniques will enable the team to look at a far wider section of the population.

“When doing this research in the past we’ve looked at the ‘elites’; wealthy people with rich graves, big houses and high cost monuments. What we’re able to do with bioarchaeology is look at burials of people who don’t have elaborate grave goods and tell their story for the first time.

“For example we can find out what they ate, how they moved around, how diet changed. We can put together a deeper, richer picture of the whole of society, rather than focussing on those at the materially visible, wealthy end of the spectrum.”

Vital

Dr Bickle admits, that like previous research, the project could present more questions than answers, but she sees that as a vital part of the research. She says: “With the new chronology we don’t know how to answer these questions about ‘gaps’ in prehistory; we only know they exist.

“Some archaeologists argue they may be caused by climate change but actually the temporal links to climate change are poor. What I hope this research will do is enable us to look in detail at how society changes over a clearly defined period. That will give us a greater understanding of the research we need to do to look at why these gaps exist.”

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Dr Penny Bickle

Research Title: Lecturer in Archaeology

The main focus of Penny's research is Neolithic Europe. She is particularly interested in how we can use burial practices to uncover the social lives and lifeways of the earliest farmers in Europe.

Explore more research

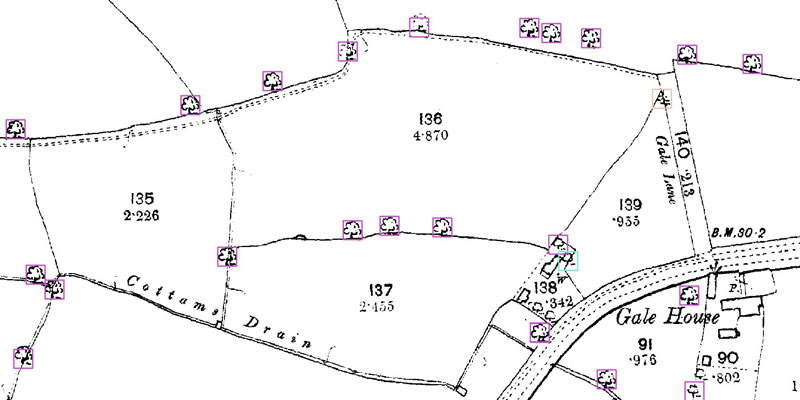

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.