Celebrating crime: How the rise of the TV corpse feeds our appetite for fictional violence

-

Research

- Culture and Communication

Posted on 17 April 2015

Why are we fascinated with crime and why is grisly violence the staple diet of TV drama? Cultural criminologist Dr Ruth Penfold-Mounce says it's important to understand our dark side...

We’ve probably seen more fictional dead bodies on TV than you can shake a stick at.”

It seems we can’t get enough of the Kray twins, the notorious East End gangsters who terrorised the London underworld in the '50s and '60s. A new film is due out later this year. They’re the subject of books, documentaries and even a London tourist trail.

So what’s the fascination with a couple of violent, murderous thugs, once dubbed the most dangerous men in Britain?

Cultural Criminology researcher Dr Ruth Penfold-Mounce from our Department of Sociology, says it’s all down to clever marketing - and the rise of mass media. Ronnie and Reggie Kray were spin doctors without training: experts at creating dark glamour out of a life of crime with an image which was reinforced by the fact they were twins.

“They used to hang out with celebrities and they always made sure they were photographed. They constructed their own myth and that’s what has helped their longevity,” explained Dr Penfold-Mounce, who was recently interviewed by the BBC’s Hairy Bikers for a TV series on British pubs - the series includes a tour of the Blind Beggar pub, a regular East End haunt of the Kray twins.

The Krays' cover story

“They knew that to survive on the street, and to have status and respect, they had to be a steel fist in a velvet glove. They needed to combine success as self-made men with illegal and violent activities. Being businessmen was their cover story.”

She argues in her book Celebrity Culture and Crime that while the folk legends of Robin Hood and Dick Turpin depended on story-telling and myth, the rise of criminal celebrities like the Krays, or the Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs, is largely the creation of TV and newspapers.

“Once you see the arrival of the mass media, these stories start to have more depth and frequency. There’s more personality, you’ve got photographs, films, newspapers - the characters become more detailed.”

Social media

And today, our interest in criminality is aided and abetted by social media which, as Dr Penfold-Mounce points out, leaves us open to the grim reality of crime, but without the 'softening lens' of fictional portrayals of crime scenes or violent acts.

“We’ve probably seen more fictional dead bodies on TV than you can shake a stick at. TV shows like Silent Witness or CSI are everywhere and a lot of these programmes are incredibly gruesome and violent - but we are really blasé about it.

“But social media and online news is changing our views of mortality. My research highlights the fact that reality is creeping in. You don’t have to look too hard on the internet to find explicit photographs and film of people being shot, executed or burnt alive. Often these images are taken by people at the scene – and these images are available on popular online newspaper sites for anybody to see.”

But while we’re comfortable watching fictitious autopsies, gruesome murders and crime scenes in the comfort of our front rooms, we’re certainly not comfortable when the brutality switches from fiction to news-based fact.

“We have become numb to fictional stories about death and crime – but suddenly we’ve got the reality of lives being lost in plane crashes and public executions on the news. This reality reminds us of our own mortality and, as a society, people find it difficult to be faced with their own potential vulnerability. The actual corpse still requires distance and respect even within a society desensitised by fictional portrayals of death.”

Celebrity criminals

Her research also highlights the rise of the phenomenon of the modern-day celebrity criminal. The Krays may have been criminals who, with the help of clever PR, became celebrities. But today, 24-hour news and our fascination with celebrity culture, has contributed to the creation of the celebrity criminal. Personalities such as Gary Glitter or Jimmy Savile are now notorious for their crimes, rather than their music or charity work. And the nature of their crimes means they are unlikely ever to earn the type of public affection reserved for people like the Krays.

“A celebrity convicted of a paedophile crime can’t make a career comeback. They are destroyed. We might admire crimes that are sneaky or clever. Robin Hood is a criminal folk hero and we all love to hate someone like Ronnie Biggs, but that’s certainly not the view of Gary Glitter.”

Dr Penfold-Mounce argues that our cultural attitudes towards crime and corpses is an area that is under-researched. But it deserves sociological examination because it provides clues to our own ambivalent attitudes to mortality and also our boundaries of acceptable violence.

Popular culture

“We have a kind of dark fascination with the macabre and also morbid criminal glamour. Popular culture gives us a way to voyeuristically watch crime but without having to be part of it.

“Television may have helped the cadaver become popular culture’s newest star,” she says, “but only when it is safely packaged as part of a story narrative.”

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Dr Ruth Penfold-Mounce

Research interests in the cultural and sociological aspects of celebrity, crime and deviance.

Publications

- Corpses, Popular Culture and Forensic Science: Public Obsession with Death is published in Mortality

- Celebrity Culture and Crime: The Joy of Transgression is published by Palgrave Macmillan

Visit the department

Explore more research

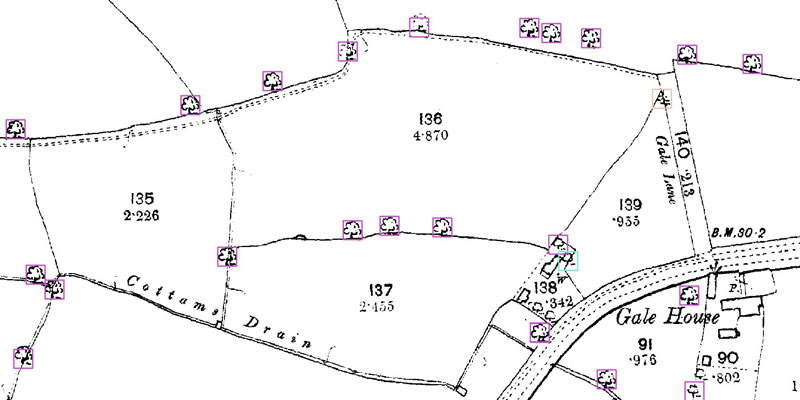

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.