Holistically understanding Hepworth

-

Research

- Creativity

- Culture and Communication

Posted on 12 October 2021

The artist Barbara Hepworth was an icon of 20th century abstract art. Her sculptures are displayed throughout the world and, since her death in 1975, her work continues to influence artists today.

Barbara Hepworth working on the armature of Single Form in the Palais de Danse, St Ives, 1961. Photograph by Studio St Ives. Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

When writing about abstract sculpture very often we tend to ‘de-materialise' the object very quickly... One of the key drivers behind this network is to consider the sculptures as objects in a more ‘rounded’ way.

Despite spending much of her working life in Cornwall, Hepworth was born in Wakefield and her art studies began at the Leeds School of Art. Strong links to her home county remain through The Hepworth Wakefield, a gallery dedicated to her work.

Now researchers at York, along with colleagues at the University of Huddersfield and The Hepworth Wakefield, have formed the Hepworth Research Network (HRN), a mix of art professionals including historians, artists, conservators and curators, who intend to stimulate new thinking around the tangible aspects of the artist’s work, and her approaches to creating, displaying and maintaining it.

Understand

Professor Michael White, from our Department of History of Art, was involved in setting up the group, which he says will help us understand the materials used in sculpted objects, and improve their care and maintenance.

“What often happens when writing about abstract sculpture, and abstract art generally, is that very often we tend to ‘de-materialise' the object very quickly,” said Professor White.

“We’ll talk about it momentarily, then very quickly move on to talk about ideas, concepts and theories - things which actually detract from talking about the artwork as a material object. One of the key drivers behind this network is to consider the sculptures as objects in a more ‘rounded’ way.”

He says the four groups are a critical part of this approach. Each has a unique way of considering artworks, but there isn’t always a great deal of interaction between the disciplines, meaning that perspectives of the artworks' fabric can be very limited.

“Conservators, for example, have a close relationship to the sculptures because they're often called on to maintain or repair them, and they get to know the works quite intimately,” he said. “They'll know how much they weigh, how they’ve changed over the years, whether they should be indoors or outdoors, and so on.

“Whereas a curator will consider the object in situ. Sculptures are complicated objects to move, and the curator must consider which way around an item should be displayed, how it will look around other sculptures or how attention should be drawn to the material itself, which often isn’t obvious at first sight.

“Our next event involves presentations by contemporary artists inspired by Hepworth. Many of them are using completely different materials and processes to those she did, or are even working in more ‘immaterial’ ways with forms of new media. Their understanding of how one might translate one material into another gives us a third completely different way to understand her artworks.”

Conversations

Professor White says it’s the conversations between these groups and their differing perspectives and experiences, which are giving rise to new thinking and knowledge beyond standard histories of art.

He says Barbara Hepworth was the focus for the network due to the rich seam of her material held at the gallery in Wakefield.

“As well as the large number of artworks at the Hepworth, they also have a large number of preparatory objects - that is objects made in the process of creating the final sculptures - there’s a collection of materials and tools, as well as a great deal of notebooks and correspondence.

“All of this makes up a very rich picture of an artist’s methods, and we’re using that as a resource in the hope we can come up with new ways of thinking about how she made things and why she made objects in the way she did.”

Influence

Any new understanding of the materials or construction processes can be of use to any person or organisation with a responsibility of caring for a Hepworth sculpture or one by a similar artist, says Professor White. He’s hopeful the network will continue to have influence when its funding closes in 2022.

“There are a lot of different types of organisations across the world that are caring for these works,” he says. “As well as art galleries, there are councils, which might have a sculpture in a park or city square, or private collectors with a Hepworth sculpture on their property.

“The University of York, for example, has a sculpture which is usually housed in the [School of Arts and Creative Technologies]. Anyone with a Hepworth in their possession will find what we’re learning useful.”

Related links

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Professor Michael White

Professor White is a Professor in History of Art working chiefly on the interwar avant-gardes. He wrote his doctoral thesis on Theo van Doesburg and has a special interest in De Stijl and modernism in the Netherlands.

Explore more research

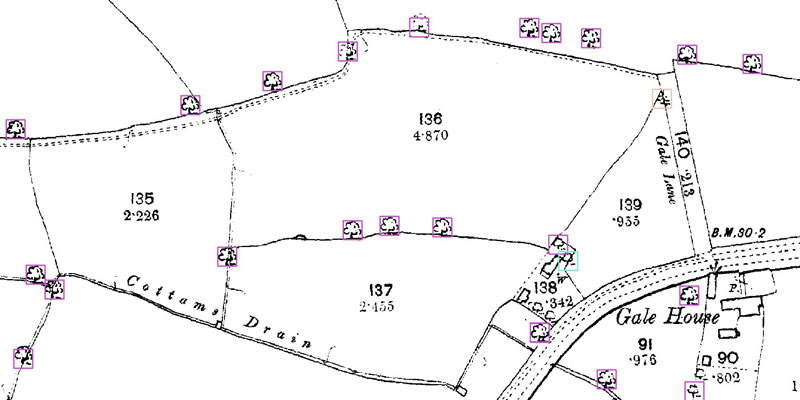

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.