Driving creativity to calm traffic chaos

Posted on 9 November 2018

For people living in many East African cities, deadly traffic chaos is a way of life. To reduce its horrific death toll, our researchers are encouraging the local people to be creative.

Local teams found creative ways to teach road safety to children in Kampala.

In Kenya there are an estimated 3,000 deaths per annum of which 40 per cent are pedestrians.

Some research can be carried out in a laboratory, some in a library. Test tubes and books are often the tools of the trade, and equations and fact enable researchers to draw their conclusions.

But much research depends of the input of ordinary people in everyday situations, and its impact matters most to the very people who contribute to it. In these cases public engagement, understanding and a means of allowing participants to express themselves openly and clearly, are as critical as the analysis and interpretation of the data itself.

The British Academy funded Implementing Creative Methodological Innovations for Inclusive Sustainable Transport Planning project (i-CMiiST) is just such an example. Dr Steve Cinderby and Howard Cambridge of the Stockholm Environment Institute at the University of York, are leading a project to tackle one of East Africa's most deadly and prolific killers: road traffic accidents. And they’re using creative research techniques to help the local population create effective solutions.

Fatalities

Cities such as Nairobi, Kampala, Accra and Dar es Salaam in the eastern region of Africa are facing a major transport crisis. Road traffic fatalities are reaching such high numbers they’re overtaking other major killers such as HIV and malaria, with the problem being particularly prevalent in younger age groups.

Roads are packed with buses and other public service vehicles - motorbikes, lorries, heavy goods vehicles and private cars all ply their trade while cyclists and pedestrians try to safely negotiate the chaotic streets.

To exacerbate the situation, a lack of regulation and enforcement mean that poorly maintained vehicles, drink and drug-related driving, a lack of driver training and poor infrastructure add to a perilous melting-pot.

Principal Investigator Dr Steve Cinderby says that, not surprisingly, it’s the poorer members of society who bear the brunt of the situation.

“They tend to walk, or rely on public transport, while wealthier citizens can afford to drive cars,” he says. “In Kenya there are an estimated 3,000 deaths per annum of which 40 per cent are pedestrians.”

He says that as well as the traumatic effects of bereavement, the poor also bear financial fall-out due to the loss of financial income.

Gridlocked

And these countries are also dealing with the economic effects of a road transport system which, in effect, doesn’t work. It leaves freight transport and logistic firms gridlocked, costing Nairobi alone an estimated Sh50 million a day in lost productivity, according to a 2016 report by the World Bank.

To enable local agencies to find solutions to their traffic problems, the team knew that stakeholder engagement and understanding would be critical and were keen to use creative research techniques to create a sense of excitement, ownership and maximise participation.

Two case studies were carried out in Nairobi and Kampala, each with two local teams working on different projects, and each carrying out several different activities.

“We’d built up local networks in the areas, which was essential because we needed to get buy-in from the transport people in those cities,” said Steve. “They were very engaged, they didn’t just want us to produce a report for them to file, they wanted to be involved throughout the duration of the project so they could help us.”

Once the local agencies had chosen the most impactive locations for the research, teams set to work explaining the issues and gathering data using the most creative methods they could think of.

Enthusiasm

Dr Cinderby says he was struck by the energy and enthusiasm the teams generated with their ideas: children were engaged with school visits and participated by painting and writing road-safety themed poems; on one street, photographers worked from a ‘Creative Photography Hangout’ to record their impression of the street’s function. Plans are even in place for a temporary 3D zebra crossing to be installed.

Teams also used huge artworks to illustrate how a dangerously congested road might be converted to include cycle and pedestrian lanes; “We talked about that particular idea one afternoon,” says Howard Cambridge. “The next day someone in the team rocked up with huge billboards, paint and an organised team. The local TV station even turned up to film us.”

These and many other types of research and communication projects have been going on for most of 2018, and Dr Cinderby and his colleagues will travel to the region in early November (2018) to reflect on the work carried out so far.

“For me this has been one of our most successful projects,” says Howard. “The teams we’re working with are really engaged. For SEI the science is important but what’s equally important how we take the science and present it to policymakers so they can use it effectively. For us, and for the people living in these cities, that’s the best outcome.”

The British Academy is the UK’s national body for the humanities and social sciences.

The Cities and Infrastructure Programme funds research that address the challenge of creating and maintaining sustainable and resilient cities, to inform relevant policies in developing countries.

It is run on behalf of the National Academies, as part of the Global Challenges Research Fund.

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Explore more research

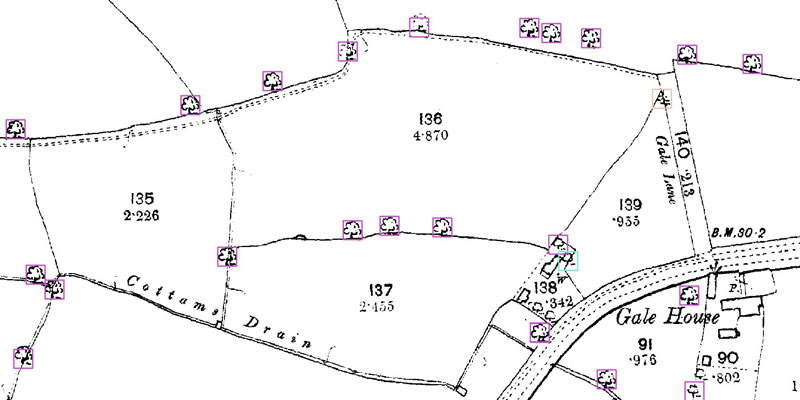

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.