Though plans for a university in York first appeared as early as 1617, it would be over three centuries before they came to fruition. In 1960, permission was finally granted for the University of York to be built, marking the beginning of our journey.

History of the University

.jpg)

Dr Heather Melville, OBE is our current Chancellor.

People

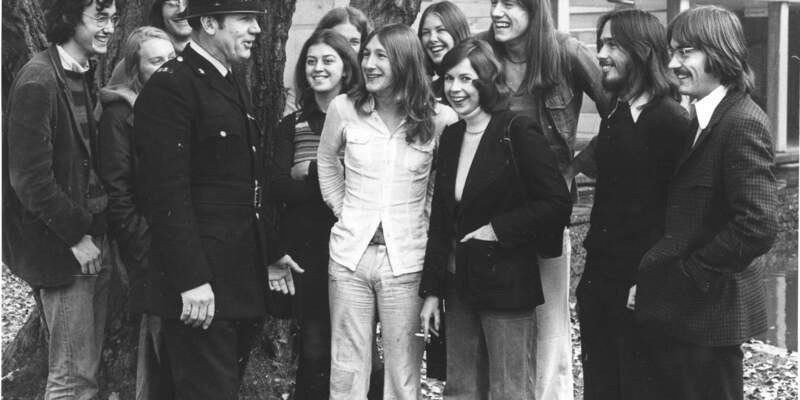

Our Chancellors, Vice-Chancellors and Students' Union Presidents have contributed to the University's development in many ways. They've led a diverse group of students, academics and support staff in building a venerable institution in sixty years.

Campus architecture

Explore our campus roots and how we've grown over time.

Dr Erhan Tamur, lecturer in the Department of History of Art, discusses the creation of the original campus and reflects on the process, evolution and the University's original vision.

Long Boi - a feather in our cap

Long Boi was a much loved duck who lived at the University between 2018 and 2023. His tall stature and friendly demeanour saw him become a cherished figure on campus, then an internet and media sensation.

Find out more about his life and how he became top of our bill.

.jpg)

.jpg)