Benefit sanctions: are they really working?

-

Research

- Justice and Equality

Posted on 11 August 2016

Research by our social policy experts casts doubt on Government efforts to get people back to work by cutting their welfare payments.

If sanctions are meant as a stick then our research shows it is a pretty big, blunt stick...”

In the 12 months to the end of June 2015 around 482,000 Jobseeker’s Allowance claimants had their benefits cut or reduced as a result of benefit sanctions. The reasons ranged from missed job centre appointments to a failure to complete required on-line job searches.

As a result, claimants had to get by on less, or no money, for days, weeks or months, causing hardship for themselves and their families.

The Government’s aim is to use these restrictions as a ‘stick’ to change the behaviour of job seekers and encourage them back to work.

But a major research project, led by our social policy experts, shows the Department of Work and Pensions might have more success if it adopted a ‘carrot’ approach, helping and supporting people into jobs rather than punishing them by cutting their payments.

“If sanctions are meant as a stick then our research shows it is a pretty big, blunt stick that often has significant negative consequences for claimants,” says Professor Peter Dwyer from our School for Business and Society.

“Supporters of benefit sanctions argue that if you make the receipt of welfare benefits or services conditional on certain types of conduct or behaviour, then people will ‘see the light’, stop behaving irresponsibly and become more likely to prepare for employment or get a job.

“But our findings so far show only limited evidence that the stick approach being adopted by the Government is actually working. It brings into question the ability of welfare sanctions to bring about positive changes in people’s behaviour.”

Survival crime

Instead, the first wave of findings from the five-year Welfare Conditionality: Sanctions, Support and Behaviour Change project show that benefit restrictions are pushing families into debt. Many claimants have to rely on charities and food banks and some have been forced into ‘survival crime’ such as shoplifting to feed their families.

Researchers from six universities in England and Scotland interviewed 481 welfare service users in the first phase of the five-year Economic and Social Research Council-funded study, thought to be the largest of its kind in the UK. Civil servants, politicians and third sector organisations also took part.

The interviews found “very limited” evidence that benefit sanctions encouraged people into paid work. Anxiety, ill health and feelings of disempowerment were common responses.

Resentment

Many felt deep resentment about what they saw as the inappropriate use of sanctions.

One homeless man told the researchers: “I got sanctioned for not going to an interview. I got sanctioned for a month… it made me shoplift to tell you the truth. I couldn’t survive with no money.”

The researchers did find some recipients who had improved their work or personal situations. But the common thread linking stories of new jobs, or changed behaviour, was not so much the threat or experience of sanctions, but the availability of appropriate individual support.

One interviewee told the team: “When I used to feel really low, I used to hit the bottle. Now… I’ll just ring (support worker) up and he’ll say, ‘Right do you want to come to speak to someone?’ Which is great… I’ve never felt more confident. I’ve got a job interview through these guys…”

Professor Dwyer explained: “Some welfare claimants face particular issues – they might be homeless or disabled people or single parents with caring responsibilities.

“There are some allowances built into the system to meet certain people’s particular needs and circumstances but these ‘easements’ do not always appear to be applied appropriately by some Job Centre advisers. When such support does happen, many of our interviewees said it was helpful.”

Universal Credit

More recently the conditions imposed on welfare claimants have been extended to include low paid workers receiving Universal Credit, a new payment currently being rolled out across the UK to replace six means tested benefits.

This means that sanctions can now be applied to people who are already employed and in receipt of in-work benefits to top up their low wages.

“This is a significant extension of the scheme and it raises the prospect of people who are in work being subject to the same sanctions as those who are out of work,” said Professor Dwyer.

“In some cases this can act as a disincentive to work, so it is important that we have research to understand the implications of applying conditions to people who already have jobs.”

Further interviews with welfare service users in cities across England and Scotland are underway. The project’s final report is due in 2018.

This research is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Professor Peter Dwyer

Research interests in social citizenship and the impact of international mobility for migrants and welfare states

Discover the details

Find out more about the work of the Welfare Conditionality project

An article outlining the project's preliminary findings, Benefit sanctions are now hitting ‘hardworking’ families, was published in The Guardian

Explore more research

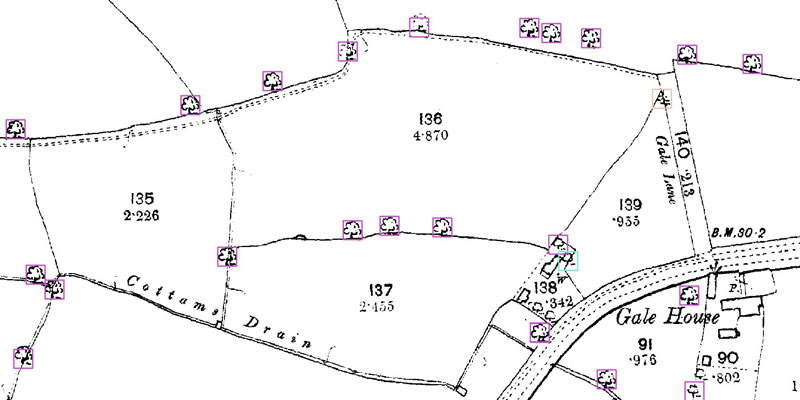

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.