.jpg)

Adapting to food insecurity in lockdown

CONTEXT

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed issues around the resilience and sustainability of our food systems with the most vulnerable hit hardest by food system shocks, such as pandemics, volatile weather and civil conflicts. The UK saw a massive increase in the use of food banks and food shortages due to supply chain disruptions that pushed consumers to change their food practices.

RESEARCH AIM

Households with children, especially those of low socio-economic status, are in general more likely to be food insecure and during the pandemic, those with young children have experienced the most significant disruption to their food practices due to school closures, furloughs, and job losses. School closures put extra pressure on families due to increased caring and food provisioning responsibilities that were previously undertaken by schools, and free food parcels during lockdowns and the Holiday Activities and Food Programme were part of an effort to support the most vulnerable children.

Some of these changes in food practices are likely to be long-term due to the economic downturn, pushing more families into poverty and food insecurity. Food insecurity, in conjunction with the obesity epidemic and the environmental impact of food, makes it vital to understand how food practices, and food consumption, change in the context of food insecurity. This can inform public policy and help create effective interventions to encourage healthy, sustainable and affordable eating in times of hardship.

The research aimed to capture the experiences of food insecure parents of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to explore changes in the food practices enacted by these families in relation to their ongoing food insecurity and wellbeing. The research asked ‘how is the COVID-19 pandemic disrupting the various food practices of food insecure parents?’ and ‘what food practice adaptations are triggered by the COVID-19 restrictions for food insecure parents?’

METHOD

Qualitative and quantitative data about families’ food practices during the pandemic were gathered. Ten low SES parents of young children were recruited. Participants completed a survey to capture their food practices, and changes, due to the pandemic. Then they were invited to participate in two in-depth interviews (May 2021 and June 2021) to further explore their experiences and the impact of the pandemic on their pre-existing food security levels. Between the two interviews, the families were also involved in ethnographic research for a period of 10 days. Using a mobile ethnography app, participants were asked to capture through pictures, videos or text their wide-ranging daily food routines, including food shopping, meal preparation, food storage and food disposal. All the images included in this brief were captured by our participants and are published here with their consent.

FINDINGS

Data illuminates significant changes to food practices during the pandemic for participants, including an increase in bulk buying, batch cooking and stockpiling non-perishable foodstuffs; more careful planning to use up leftovers and freezing meals for the week ahead; and a new reliance on planning apps. Families increased their efforts of planning ahead to maximise their food shopping and preparation efficiency, and spent more time in the kitchen, preparing meals from scratch to save money. However, they also turned to comfort food during the lockdown as an emotional coping mechanism, which dramatically increased their junk food intake. With the additional pressure on individuals’ physical and mental health, maintaining a balanced diet has been a struggle for lower SES families with young children.

Changing food acquisition practices

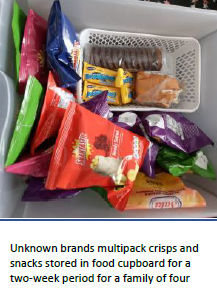

The anxiety associated with going to the supermarket during the COVID-19 pandemic reduced participants’ regularity of food shopping trips, encouraging families to shop online and bulk buy to stockpile on certain ingredients such as flour, tins, rice and pasta. Some families opted for food deliveries, while others were able to rely on their community, local food banks and neighbours for support. For food insecure participants, this increased the precariousness of their access to food, due to limited physical availability of food items and increased financial problems. These multi-layered anxieties triggered enhanced planning to ensure food shopping stayed within a fixed budget. Participants used grocery lists and apps on a mobile phone, and shifted their habits away from impulse buying behaviour. Participants balanced concerns about value and freshness of the products with a need to opt for the less expensive foods, including unknown brands when possible. Preferences for non-perishable and inexpensive foods increased. Meat consumption reduced and families attempted cheaper alternative meals.

Changing food preparation practices

Families reported consuming more food at home, enjoying and experimenting with home cooking despite their tight budget. In all families, respondents expressed satisfaction to spending more time cooking and experimenting with new recipes. Eating together was an important aspect of the lockdown as families were gathering to have meals. The respondents also reported a reduction in using ready meals and takeaways, with a shift towards homemade options. Although low socio-economic families expressed their desire to eat fresh fruit and vegetables, it was costly for them. Non-perishable products such as flour, rice and pasta were heavily consumed, and families reported an increase in making bread, cakes, pasta dishes and pies from scratch. The increased time at home, due to social restrictions (the ‘lockdown’) and working from home arrangements, may have encouraged families to spend more time preparing food, improving their cooking skills and nutritional knowledge and benefit from family bonding. In an effort to treat their families to homemade tasty food, many participants reported using the internet to discover new recipes and ingredients as well as new food preparation techniques and freezing techniques that also saved time and money. They also searched for practical and simple recipes to use up leftovers and avoid wasting any food. Many families reported better use of leftovers and less food waste. In the long-term, support in maintaining these practice adaptations could have a positive environmental impact.

Eating changes

The interviews and ethnographic data showed an increase in snacking over set mealtimes and an increase in consumption of comfort food throughout the day. During lockdowns and home-schooling, children were asking for food more frequently and this put extra pressure to tight budgets and stressed parents to come up with new meal ideas. Changes in families’ eating habits, tracked during the lockdown, therefore demonstrate both increases in snacking, creative use of leftovers to minimise food waste and families eating together. Families reported eating chocolate, sweets, crisps and snacks more often.

Changing food storing practices

In an attempt to save money and to stockpile to avoid future food shortages, families started to use new techniques to keep foodstuffs fresh and tasty by chopping ingredients and freezing them in storage bags. Ideas found on the internet were very useful. Families have bought storing boxes and dedicated shelves in their kitchen to store extra tins, pasta and rice, and flour packs due to bulk buying. Some families reorganised their kitchen in order to have more space for storage.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Findings suggest that food insecurity was exacerbated by pandemic restrictions, but that parents adapted practices creatively, in line with broader trends. Positive outcomes, such as enjoying the family bonding while eating together and the creativity of cooking from scratch, as well as negative outcomes, such as the need to adapt rapidly and in multiple ways combined with financial and emotional pressures, were experienced. Therefore, it is vital for the food system stakeholders and policymakers to use the pandemic learnings as an opportunity to support lasting change, particularly supporting lower SES families to develop food routines that will be more resilient to future disruptions. For example, planning, preparation and storage solutions for affordable and healthy meals should be matched by provision of affordable, local and healthy ingredients available to the most vulnerable groups. Rather than placing the responsibility on families, we recognise that actors from across the food industry are important stakeholders in food system transformation. The below recommendations highlight the implications of our findings in how low SES families and communities can be supported:

1. Community-based programmes

Communities need continuous access to high quality, sustainable food which could be achieved through programmes that offer families the needed support and suitable food options. Local authorities must invest in community-based programmes such as community gardens, food clubs and local enterprises-farmers collaborations to bring healthy and sustainable food to the community and particularly to those in need. These should be beyond food to ensuring appropriate material arrangements (such as access to a freezer or ability to pay for electricity) are in place.

2. The Role of Schools

Schools can provide an ideal site for instilling healthy habitual practices and a positive relationship with healthy and sustainable food. Therefore, there is a need to prioritise interventions that promote healthy behaviour and sustainable lifestyles across education settings. Food planning and preparation, food waste management and cooking skills can be embedded in the school curriculum, promoting healthy and sustainable food practices to keep the momentum of home cooking and reduced food waste that families gained during the pandemic.

The impact of school closures have been highlighted in the study findings. Therefore, schools, supported by local authorities, should continue to provide healthy meals in the case of school closures and during holidays to the most vulnerable families, aiming not only at hunger elimination but also at increasing fruit and vegetable intake.

3. Public Health Communications & Social Marketing Campaigns

There are opportunities for building on the positive experiences of skilful adaptation and developing these skills across the population more broadly. Public health communications and social marketing campaigns should focus on normalising cooking with local and seasonal products, promote economically friendly recipes that highlight different methods for stretching limited ingredients, ideas for swapping ingredients, inspire consumers with recipes to use up leftovers to create new meals and encourage consumers to freeze foods to reduce waste. Several budget cookery techniques could be introduced as part of social marketing interventions. For instance, there is an opportunity to encourage meal planning using apps, keeping track of what is in the fridge/cupboards before food shopping, but also batch cooking or home freezing and using cheaper alternative ingredients.

4. A Right to Food Approach

Finally, the ongoing economic downturns and the impact of the pandemic has led to an understanding that food insecurity can be experienced by anyone, and that insecurity encompasses a number of practices and practice adaptations that are fluid, oscillating and volatile. Therefore, access to healthy and sustainable free school meals, community support and food clubs must be open, consistent and marketed so that people can access them without stigma in the context of a right-to-food approach.

About the authors

.jpg)

Dr Hela Hassen

Research Title: Lecturer in Marketing

Hela’s research focuses on social exchange, reciprocity, and food practices.

.jpg)

Dr Ariadne Kapetanaki

Research Title: Lecturer in Marketing

Ariadne's research focuses on the nexus of social marketing, food practices, public health and policy.

.jpg)

Dr Fiona Spotswood

Research Title: Senior Lecturer in Marketing

Fiona’s research focuses on understanding how marketing can, and does, shape the normativity of practices that have an impact on consumer wellbeing.