Sea, Soil and Extraction: The Guano Industry in Twentieth Century Seychelles

Theo Tomking shares how guano in the Seychelles enriches our understanding of the ecological and social tensions in historical efforts at modifying soils.

Bird excrement was big money in the Indian Ocean during the early- to mid-twentieth century. Over hundreds of years an ecological process involving marine animals, seabirds and the geology of some Seychelles islands resulted in the accumulation of vast deposits of a remarkable substance: guano, or ‘kaka zwaso’ in Seychellois Kreol. The story of this substance, and the economic wealth accumulated because of it, enriches our understanding of the ecological and social tensions in historical efforts at modifying soils.

Guano in the Seychelles started in the sea and ended in the soil. As generations of seabirds consumed marine animals in the Indian Ocean, they often deposited the un-digested nutrients as excrement on the islands they used to nest and raise their young. Where significant quantities accumulated on islands with a calcareous subsoil (such as the many coralline islands of the Seychelles Archipelago), rain and sea surf caused the organic matter and phosphates from the excrement to leach into the bedrock. Whilst the organic matter will have decomposed, the phosphates did not, and were left to react with the calcium carbonate in the subsoil to form ‘rock guano’.[1]

What made this substance remarkable was its high concentration of phosphates – one of the key nutrients, alongside nitrogen and potassium, needed for optimum plant growth. As a component of ATP (adenosine triphosphate), phosphates are essential for energy transfer in plants and play a role in fundamental processes such as photosynthesis, genetic transfer and nutrient transport.

Crushed up and applied to the soil surrounding crops, guano made a potent fertiliser for the benefit of Seychelles’ agricultural industries. For example, on the coconut plantations that once sprawled across the plateaus of Mahé (the highest populated and largest granitic Seychelles island), planters found in guano a seemingly inexhaustible resource to boost coconut yields and ultimately profits from their exportation as copra.[2] Some planters were known to apply up to one ton of guano on just a single coconut seedling, in one go! This required digging holes seven feet deep so the sheer volume of guano would fit beneath the seedling when planted. By 1936, the potency of guano was better understood and far less was used. This was partly a response to certain cases of hard pan layers forming in the soil due to excessive use.[3]

Later in Seychelles’ history, the Ministry of Agriculture also sold guano to local smallholder farmers. Some farmers would mix the guano (sold in fine powder form) with compost and apply the mixture to soils to improve plant growth.

The use of guano in Seychelles will have almost certainly boosted the yields of export crops like coconut and influenced the ways smallholder farmers treated their soils. As such, the use of guano can be seen as an anthropogenic connection between sea and soil in the Indian Ocean – an appropriation of the labour and nutrient flows of centuries of marine and bird life that had produced a valuable substance for agricultural production. However, the story of Seychelles guano is not just a domestic one.

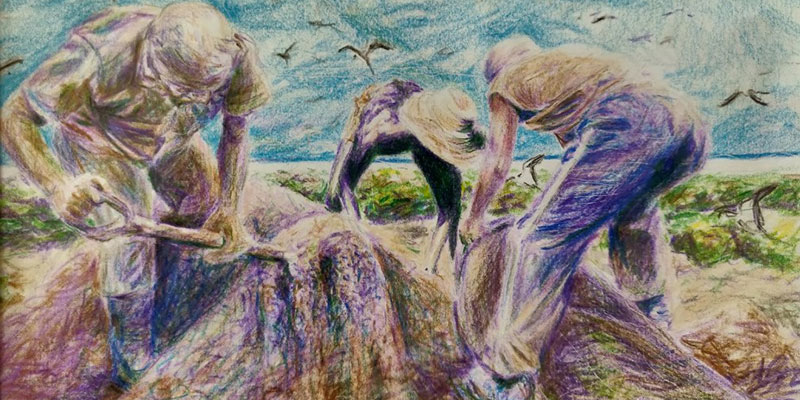

Cross-section of a block of guano. After being mined, guano blocks like these were crushed into a fine powder for use as a phosphate-rich fertiliser. Photograph by Theo Tomking, 2022.

The guano extracted from Seychelles islands was exported across the world, tracing an international network of agricultural interests from nearby Mauritius, Kenya and Madagascar, to New Zealand, Britain and elsewhere.

To construct this international export trade required a system for the extraction of guano. Labourers, mainly from Mahé, were transported to islands with guano deposits to mine it from the bedrock. In-turn, they were given a monthly wage and rations. Working conditions were poor and physically demanding, with loading of the guano onto ships done by hand. Considering that 60 tons could be loaded in one day, it would have been exhausting work. Correspondence from the Governor of Seychelles in 1905 (Walter Davidson) paints a picture of the working conditions. As Davidson writes: “on some islands I have suspected cases somewhat akin to ber-beri, probably due to the water - or the inhaling of the guano dust”.[4] Considering that Davidson also recommended a doctor visit the islands, we can infer that work-related health issues were bad enough to warrant concern amongst even the elites of Seychelles’ political infrastructure.

To add to the risks that such work involved, much of the guano deposits were on outer islands, so the transportation of guano back to Seychelles’ main port on Mahé could entail spending days at sea navigating dangerous currents – the distance between Mahé and the Aldabra Group of islands, for example, is over 1,000 kilometres. As Davidson writes in 1905: “The actual loading of guano is often accompanied by difficulty. … At all times there is a risk in navigation owing to the strength of the currents; experienced local men can be hired to advise the master in navigation”.[5] These records paint a picture of early guano extraction as a dangerous endeavour, built upon strenuous manual labour under poor working conditions. As you might imagine, the fruits of this labour were not evenly distributed.

Port Victoria, Mahé – the largest port in Seychelles. Guano from other Seychelles islands was collected here, then exported across the world. Photograph by Theo Tomking, 2022.

A significant portion of the profits from the guano industry went to those who owned or leased the islands with guano deposits. These were mostly individuals, but companies also ran mining operations in some circumstances. In 1906, for example, St Pierre island was leased by the Crown to a ‘Mr Jounais’, whereas the entire Aladabra and Cosmoledo Groups, Astove and Assomption islands were leased by a ‘Mr Adolphe d’Emmerez de Charmoy’.[6] Such individuals would have received the profits of the guano sold to exporters.

The other main portion of the profits went to the exporting companies, who ran the shipping operations that took guano from Mahé to other ports such as Mombasa, Ghent, Hamburg, Granville, Port Louis, Liverpool and London. The Seychelles Guano Company Ltd (later known as ‘The Seychelles Company Ltd’) was one of the largest exporters of Seychelles guano. In 1936, for example, they shipped just over 10,000 tons, supplying London, Liverpool, New Zealand and Mauritius.[7] With an office in Blackfriars in London, a chunk of the Company’s profits was likely syphoned into the pockets of wealthy individuals stationed thousands of miles from Seychelles, indicating the type of extractive economic relationship that existed between British capital and Britain’s colonial possessions in the early-twentieth century.

In 1930 alone, total guano exports from Seychelles were valued at 376,063 Seychelles Rupees – more than 3,000 times the annual earnings of the average guano miner.[8] From 1945 to 1950, a total 87,956 tons of guano left the Seychelles, worth roughly £4.8 million in today’s money.[9] By 1963, around 700,000 tons of guano had been exported in total.[10]

However, these profits came at the expense of not just the workers, who had to deal with brutal working conditions, but also the ecology of the islands that were mined. The type of guano found in Seychelles was a finite resource, and removing it required taking a part of the island itself. On the island of Assomption, where over 160,000 tons of guano had been removed by 1945, the loss of tree cover removed the nesting sites of what is now one of the rarest seabirds in the world: Abbott’s Booby (Papasula abbotti). Since 1909 reports claimed the species was extinct on Assomption, and today it is only known to nest on Christmas Island, on the other side of the Indian Ocean.[11]

St Pierre island, one of the last to endure mining operations, shared a similar fate. A description of the island from a 1968 soil survey paints a grim picture: “Only about twenty species of plants are present and, except for a few cèdres, the only surviving tree is a mapou (Pisonia grandis) in the centre of the island”.[12] A more recent description of the island labelled it a “virtual ecological desert”.[13] These are just two examples which show how extracting guano undermined the ecological integrity of some Seychelles islands.

By the early 1980s, the Seychelles guano industry had started to cease. Mining on Assomption, for example, stopped in 1984.[14] Though the reasons are not clear, the decline of the industry might have been due to dwindling supplies. As early as 1935, concerns had been raised over the quantities left on some islands. Often, these were followed by discoveries of new deposits and continued extraction, as was the case with St Pierre.[15] Perhaps the islands had been too exhausted by the 1980s to justify continued extraction? Another potential reason for the decline of the industry was the changing economy of Seychelles. With the opening of the airport in 1972, tourism became increasingly important as an alternative to guano exports and agriculture as the basis of Seychelles’ economy. For whatever combination of reasons, it was clear by the 1980s that the money was elsewhere.

As the exportation of guano dwindled there were also changes in its domestic use in Seychelles. A fertiliser scheme was introduced in 1959 to try and revive the struggling coconut industry. However, instead of guano being used, imported synthetic fertilisers were distributed to planters, likely containing ammonia synthesised from the Haber-Bosch process, as well as phosphates and potash obtained from rock mined elsewhere. In 1959, 185 tons of imported fertiliser were distributed; followed by 305 tons in 1960 and 214 in 1961. Interestingly, demand for imported fertilisers dropped in 1962 as the purchasing capacity of coconut planters fell.[16] To this day, farmers in Seychelles still have to grapple with the prices of imported fertilisers.

Today, many of the previous guano islands have been transformed into nature reserves, open to visits from tourists, local Seychellois and researchers. On Aride island, for example, the remnants of mining can be seen in the piles of abandoned blocks of guano scattered across the forest floor. On the southern plateau, an abandoned building rests below the forest canopy, engulfed by thick vegetation. Through conservation efforts, Aride has become a nesting ground for various seabirds, such as brown and lesser noddies, white terns, and white-tailed tropicbirds. Endemic plant species have been nurtured too, such as ‘bwa sitron’ (Wright’s Gardenia) – a critically endangered tree now found only on two Seychelles islands. Furthermore, attitudes towards soils on Aride have undergone an almost paradigmatic change. On the same land that was previously mined for guano, conservation rangers now take samples of soil invertebrates to measure their diversity and check for invasive species. Soil is now seen as a living entity, rather than an impediment to be swept aside for mining. Overall, this is a very different situation to that indicated in a 1968 description of Aride as “exceptionally dry with very poor vegetation cover…[and] a few small patches of partly eroded Red Earth”.[17] Cases such as Aride instil hope for the power of nature in the face of extraction and destructive interference.

A white tern (Gygis alba) on Aride island – one of the many species of seabird now nesting there. Photograph by Theo Tomking, 2022.

With recent global events bringing fertilisers to news headlines once again, the story of Seychelles guano reminds us that the links between industrial fertiliser inputs and unsustainable (and arguably extractive) supply chains is nothing new. Though the days of guano are largely gone,[18] our agricultural systems are still reliant on inputs of finite resources. The phosphates that made Seychelles guano so useful are now obtained by mining limited deposits of phosphate rock. The case of nitrogen is equally stark. According to recent estimates, global ammonia production, of which around 70% is used as a nitrogen source for fertilisers, accounts for roughly 2% of total final energy consumption and 1.3% of CO2 emissions from the energy system.[19]

How we build and maintain soils that can support the growth of healthy and nutritious plants is one of the key challenges faced in agriculture the world over, as evidenced by the FAO’s Global Symposium on Soils for Nutrition held in July this year. There is much work to do and going cold turkey on industrial fertilisers is not necessarily the solution, as recent events in Sri Lanka show, where ex-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s sudden ban on chemical fertilisers has crippled yields and people’s livelihoods.

Whichever way forward we take, the history of Seychelles guano has some lessons to help guide us along the way. For one, I believe this story shows the importance of ontologies of soils. The guano industry existed because a technological vision for its use did too – a vision, I believe, that understood soil as a receptacle for chemical inputs. However, other understandings, representations and meanings have been assigned to soils in different contexts. Understanding these, I believe, can help uncover the roots of current attitudes towards soils and can aid in working towards a better alignment between food production and the integrity of non-human life.

Research for this blog post was conducted with the help of staff at the University of Seychelles and the Seychelles National Archives.

[1] Ewald Schung, Frank Jacobs and Kirsten Stöven, “Guano: The White Gold of the Seabirds”, in Seabirds, ed. Heimo Mikkola (London, IntechOpen, 2018)

[2] Copra is dried coconut kernel. It was a significant part of Seychelles’ agricultural economy in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries

[3] James Ozanne, Coconuts and Créoles (London: Philip Allan, 1936), 169-171

[4] Seychelles: dried bananas, kapok, mineral guano, 1905-1906, AY 4/1048, The National Archives, London

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Guano: Seychelles, 1937, CO 852/91/3, The National Archives, London

[8] Colonial Reports – Annual, Seychelles Report for 1930, No. 1560, Seychelles National Archives, Mahé

[9] Colonial Office Report on Seychelles for the years 1949 & 1950, Seychelles National Archives, Mahé

[10] B.H. Baker, Geology and Mineral Resources of the Seychelles Archipelago, Memoire no. 3 of Geological Survey of Kenya (Nairobi: Government of Kenya, 1963), vii

[11] Adrian Skerrett, Telma Pool and Judith Skerrett, Outer Islands of Seychelles (Nairobi: Camerapix Publishers International, 2010), 73

[12] C.J. Piggott, A Soil Survey of Seychelles, Technical Bulletin no. 2 of Ministry of Overseas Development (Surrey: Land Resources Division, Directorate of Overseas Surveys, 1968), 61

[13] Skerrett, Pool and Skerrett, Outer Islands of Seychelles, 62

[14] “Assomption”, Islands Development Company Ltd, accessed August 30, 2022. http://www.idcseychelles.com/assomption.html

[15] Guano: Seychelles, 1935, CO 852/11/10, The National Archives, London

[16] Seychelles Report for the years 1961 and 1962, Seychelles National Archives, Mahé

[17] Piggott, A Soil Survey of Seychelles, 52

[18] Guano is still mined and exported from some countries such as Peru. However, global use of guano pales in comparison to that of synthetic fertilisers

[19] International Energy Agency, Ammonia Technology Roadmap: Towards more sustainable nitrogen fertiliser production (France: IEA, 2021), 1. https://www.iea.org/reports/ammonia-technology-roadmap

Related links

Find out more about Theo Tomking's research.

Related links

Find out more about Theo Tomking's research.