Extreme gardening - 300 years before the Chelsea Flower Show

-

Research

- Creativity

- Culture and Communication

Posted on 24 May 2016

As Chelsea Flower Show unfolds this week in all its splendid, brightly coloured glory, Research Associate Dr Emanuela Vai takes us back over 300 years to reflect on an overlooked pioneer of Renaissance garden and water feature designs.

In 1620, de Caus filled up an entire section of the Friesenberg valley and cut off a mountain side to create the terraces at Heidelberg Castle in Germany, one of his most ambitious garden creations

His meticulously detailed hand-drawn garden designs... resemble the beautifully complex geometrical patterns found on butterfly wings.”

Chelsea Flower Show blooms for only five days each year and consists of a variety of elaborate show gardens full of beautiful flowers, complex water features and landscaping. As the centre piece of the event, the show gardens are certainly impressive.

But even with 21st century technology and the latest landscaping techniques, few match the extravagant and technically accomplished designs of Salomon de Caus (1576-1626), the forgotten French genius of Renaissance and Early Modern garden and water feature design.

As a Research Associate in our Centre for Renaissance and Early Modern Studies, I am currently conducting the first English translation of a very rare unpublished manuscript of de Caus’ as part of a larger project to reassess the works of this gifted historical figure.

The da Vinci of gardening?

As well as a garden designer, de Caus was also an accomplished architect, engineer, mathematician and scientist. His story says something important about the way gardening and garden design as cultural practices have changed over the centuries.

During the Italian Renaissance in particular, gardens achieved elevated status as technical and aesthetic forms. Inspired by classical ideals of symmetry, order and beauty, these gardens embodied the scientific and philosophical imperatives of harmony and proportion.

They began to incorporate architectural features designed to delight and impress, such as banqueting houses, loggias, follies and grottos. They became spaces of imagination and also places of pleasure for secret rendezvous and romantic trysts.

Water was especially symbolic in the Renaissance garden: water fountains became metaphorical stand-ins for the fons vitae or ‘Fountains of Life’ and water itself was associated with fertility and represented man’s mastery over nature – while also serving as a not-so-subtle display of the owner’s wealth.

The gardens designed and constructed by Salomon de Caus were some of the most extreme gardening projects of the late Renaissance period.

Throughout his life he was employed as an engineer and architect of buildings and gardens in several European courts and he designed a number of famous gardens including those at Hatfield House for Lord Salisbury, and at Somerset House and the Royal Palace at Greenwich for James I.

Moving mountains

In 1620, de Caus filled up an entire section of the Friesenberg valley and cut off a mountain side to create the colossal terraces at Heidelberg Castle in Germany.

Feats of landscaping aside, de Caus famously populated his elaborate and technically accomplished gardens with fantastical Heath Robinson-style inventions including musical fountains, hydraulic grottos, water organs, burning mirrors and other mechanical automata.

Perhaps a tad ornate for the Chelsea Flower Show, his imaginative creations included a water-driven automaton featuring mechanical birds that sang and fluttered, a water-driven swan that drank water from the fountain's basin, a cyclops that played a flageolet and a statue of Galatea that appeared to ride a seashell drawn by dolphins.

Mostly driven by waterwheels, these fantastical mechanisms were typically put in motion and made to play music by jets of water from concealed pipes.

Beyond the garden walls

But de Caus also needs to be understood beyond the confines of early modern garden design in which scholars typically enclose him. He belonged to an almost forgotten tradition of 17th century skilled artisans and makers of machines who regarded ‘knowing’ and ‘making’ as inseparable, materially entangled harmonic processes.

My research aims to reintegrate his theories of optics, astronomy, harmony, music and mechanics into his intellectual profile, along with the materiality of his sundials, water machines and musical instruments.

Studying de Caus’ plans and drawings of gardens is like looking through a 400-year-old black and white kaleidoscope. His meticulously detailed hand-drawn garden designs, rendered in birds-eye-view, resemble the beautifully complex geometrical patterns found on butterfly wings.

By exclusively focusing on de Caus’ garden designs, scholars have dramatically overlooked the distinctive conceptualisations of materiality and harmony contained within his body of work – particularly his writings on music and architecture.

Analysing his philosophy and practice of materiality and harmony could be especially useful for helping art and architectural historians to better understand music and architectural practices and theories in the Renaissance and Early Modern period.

Mechanisms and music

While de Caus’ mechanised and musical gardens never achieved the same fame as the rock stars of the garden world – the Eden’s, Babylon’s and Gethsemane’s – his designs, inventions and his thinking are not without considerable importance. Not only did they transcend their time but they anticipated developments in mechanical engineering and architecture that would not begin to take place for at least 200 years after his death.

If Salomon de Caus were alive today, I wonder if he would unveil a digital garden at the Chelsea Flower Show?

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Dr Emanuela Vai

Research interests in art and architectural history, musicology and the performative, material and aural dimensions of architectural spaces in the Renaissance and Early Modern period

Discover the details

Find out more about the work of our Centre for Renaissance and Early Modern Studies

Explore more research

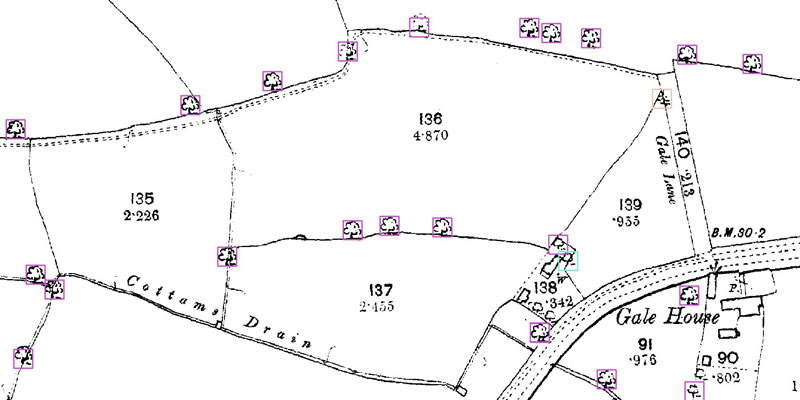

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.