Medicine's heroes and villains

Posted on 1 February 2007

The history of medicine begins with Hippocrates in the fifth century BC, yet until the invention of antibiotics in the 1940s, doctors, in general, did their patients more harm than good, he writes.

Professor Wootton is prepared for a barrage of dissent from some readers. "My book is controversial because most historians avoid writing about progress in history," he says. "It is common sense, though, that the health of humans has advanced enormously. Look at the fall in the death rate of tuberculosis. But medical treatment is not the main cause of the reduced TB death rate in the 20th century. Before the treatement became available, people were already fighting off tubercular infection due to greatly improved nutrition, especially foetal nutrition, and superior hygiene." Similarly, of the 35-year increase to average life expectancy in the 20th century, only seven years can be attributed to the success of medical treatment by physicians.

Bad Medicine is the first general history of medicine to acknowledge how often doctors do harm by ignoring evidence and sticking with tradition. Repeatedly, major discoveries which could save lives were met with professional resistance, say Professor Wootton. The first patient effectively treated with penicillin was in the 1880s; the second not until the 1940s. Nitrous Oxide was known to be an anaesthetic - but was not used to help human patients until 50 years after its first discovery, long after its first use in veterinary surgery, for horses.

Professor Wootton was partly stimulate to write Bad Medicine when he observed his daughter Lisa train to be a doctor and some of her experiences feature in the book. (She is now a qualified psychiatrist.) He was particularly struck by the content and style of teaching she received, and the type of medical profession she was expected to enter. Concerned, he sought information about how the profession had evolved in this way, only to find that medical history books seemed too close to physicians and too uncritical. So he wrote the book he had hoped to find.

In his view, the great leap forward was made 150 years ago with understanding of theory of germs. "But the theoretical understanding was already there at the end of the 17th century - why the delay?" he queries. "It is virtually forbidden in the historical profession to make a judgement about a historical character, but you can't describe a debate between scientists without taking sides. I have named the people I think are heroes and villains of medicine."

Both the medical and history professions will find his approach a challenge.

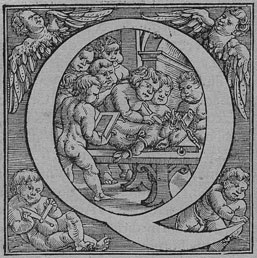

The illustrated Q from the 1555 edition of De Humani Corporis Fabrica by Vesalius, the 16th-century Belgian anatomist and physician. It shows putti or cupids vivisecting a boar. One of them is holding a textbook, possibly by Galen, a well-known doctor in the Roman Empire. During his research, Vesalius showed that the anatomical teachings of Galen, revered in medical schools, was based on the dissections of animals even though they were meant as a guide to the human body. In his book, Professor Wootton argues that modern physiology is founded in vivisection, but the knowledge gained was of no value for medical treatment until the late 19th century. |

|

About the researcher

David Wootton is a Professor in the Department of History

Contact

Email: dw504@york.ac.uk

Further information

Buy the book

Buy Bad Medicine: Doctors Doing Harm Since Hippocrates

(Amazon.co.uk)