Youth Inequalities in Focus: The Personal and Financial Costs of Youth Unemployment and Economic Inactivity

Posted on Thursday 30 October 2025

.jpg)

Growing concerns surrounding what has been framed as a crisis in youth unemployment and economic inactivity, resulted in a pledge from the Chancellor at the Labour Party Conference to “abolish long-term youth unemployment”. The key policy instrument through which to achieve this involves bolstering the Government's Youth Guarantee so that young people out of work, education or training for 18 months will be guaranteed a work placement.

Recent figures estimated that there are just under 1 million young people aged 16-24 who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) (ONS, 2025) which equates to roughly 1 in 8 young people (16-24) in the UK. Analysis from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation shows that a significant number of young people, 600,000, will be long-term NEET (remain out of work or learning for more than 12 months), of which 300,000 are out of work or learning for more than 2 years (Casey, 2025). Despite some fluctuations over time, NEET figures have remained stubbornly high and when compared to other OECD countries the UK fall behind in making progress in reducing NEET rates (Youth Futures Foundation, 2024).

Research continues to emphasise how social inequality shapes young people’s outcomes in later life and how many of these impacts are not equally felt. Where young people come from matters, and spatial characteristics such as educational provision and local labour markets have a significant impact on how their lives turn out (See Wenham 2020). Young people are also much more likely to be NEET if from underrepresented and disadvantaged backgrounds, are ‘looked after’, have a disability, have SENs, or are a young carer (Wenham, 2015). There is a wealth of evidence on the long-term scarring effects for young people, including a strong association between adversity and future labour market participation (Elsenburg, et al., 2025). An association between childhood adversity and long-term use of social benefits is partly explained by early school leaving (Bennetsen, et al., 2025), whilst experiences of childhood adversity are associated with risks of belonging to high-intensity user groups across various public service systems including health, welfare and criminal justice later in life (Kreshpaj, et al., 2025). The place-based dimensions of becoming NEET also come to the fore when looking at regional disparities, with 15% of young people in the North East aged 16-24 being NEET, compared to 9.4% in South West England (Youth Futures Foundation, 2025).

The Changing Nature of Youth Economic Inactivity: Rising Levels of Youth Ill Health

These challenges are not new. Policy responses over the years have included a range of wage subsidy schemes, varying in scope and duration, and shaped by both political will and changing economic circumstances. Back in 2009 we had the Future Jobs Fund, followed by a watered down Youth Contract (2011), and then in response to the impact of Covid-19, a Kickstart scheme (2020) was introduced. Like the proposed Youth Guarantee, these schemes have provided government funding to employers to create jobs for young people.

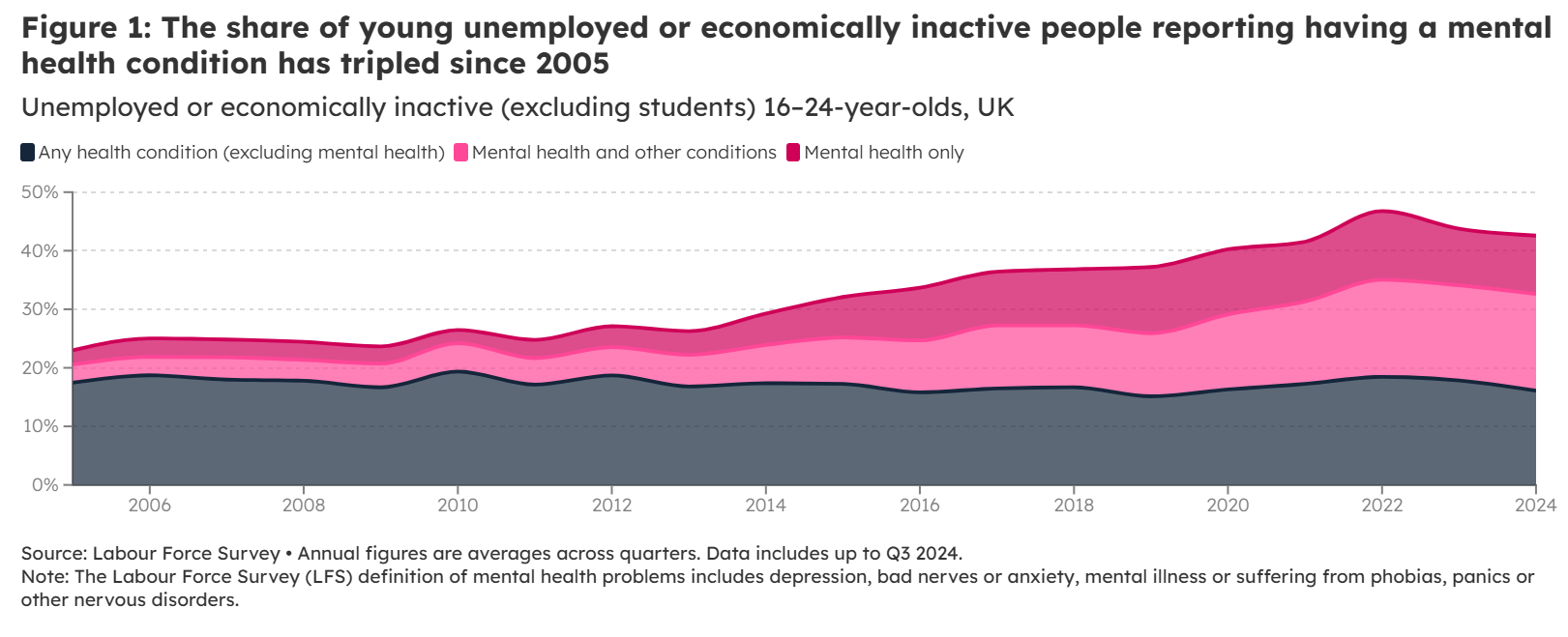

More recently, however, attention has shifted to the relationship between economic inactivity and young people’s ill health. Of particular concern is the rising number of young people who are unemployed or economically inactive reporting poor health, including mental ill-health.

Share of Young Unemployed or Economically Inactive People Reporting a Mental Health Condition

This begs the question, what is it about the wider conditions in which young people grow up - our education institutions; pathways into good employment; our social security systems - that could explain the crisis in youth mental health and its subsequent impact on economic inactivity? We know that young people spend longer periods in education and face rising levels of insecure and precarious employment, and that transitions to adulthood have become increasingly complex and uncertain than those of previous generations. When examining young people's outcomes over the lifecourse, inequalities amongst young people have only deepened, illustrating how youth transitions are becoming increasingly polarized. Young people at greater risk of experiencing long term NEET face some of the most profound forms of disadvantage and these often stem from multiple and overlapping forms of adversity in childhood.

There are currently around 200,000 young people (16-24) who are claiming benefits and deemed too ill to look for work (Phipps et al., 2025). In order to better understand the changing nature of youth inequalities, we need to unpick how young people’s ill health is both a cause and consequence of youth unemployment and economic inactivity.

Recent government announcements to support employers in providing jobs for young people are welcome. However, there are important lessons to be learnt from past policy interventions, and given the scale of the issues at hand, we need to question the degree to which these measures go far enough. An ambitious youth policy agenda entails substantive investments in youth services, holistically targeting young people who face the greatest adversities and encounter the most profound barriers to employment. Considering the relationship between ill health and economic inactivity, it is clear we need better evidence and deeper understanding of the drivers of poor mental health to develop interventions that effectively respond to the challenges young people face today. Importantly, as young people’s lives become more complex, youth policy needs to ensure it addresses the many interconnected issues with long-term, comprehensive, joined-up approaches.

Future Research: Born in Bradford Centre for Social Change

The Born in Bradford Centre for Social Change at the University of York (BiB CSC) is a collaborative initiative between the world leading research programme Born in Bradford (BiB), the Healthy Livelihoods team within Health Sciences at York and The York Policy Engine (TYPE). BiB CSC is leveraging evidence, innovative policy engagement, and community-driven approaches to address societal challenges. The Centre is exploring these topics through new projects that are exploring youth and inequality to underpin appropriate policy responses, including:

Youth, Benefits, and Mental Health

Dr Aniela Wenham is investigating how welfare policy affects the mental health of under-25s. Comparing different localities (Bradford and Scarborough), she is exploring the links between welfare conditionality, sanctions, and insecure employment, aiming to inform youth-responsive welfare and employment policy.

Pathways to Adulthood: Supporting 16–18-Year-Olds in Bradford Using data from the Born in Bradford Age of Wonder project

Dr Adam Formby is examining youth transitions in a context where high numbers of young people are in poverty and not in education, training or employment (NEET). Co-produced with young people and service providers, this research will develop actionable insights for improving education, employment, and wellbeing outcomes.

This article is a companion piece to a report taken to the 2025 Labour Party Conference which you can read here: Addressing Youth Inequalities Through Poverty Reduction Nationally and Locally (PDF ![]() , 1,437kb)

, 1,437kb)