New study to probe the secrets of our wandering minds

-

Research

- Health and Wellbeing

Posted on 27 May 2015

For most of us, meandering thoughts are nothing more than an annoying distraction, but for psychologist Dr Jonathan Smallwood they present a fascinating cognitive puzzle.

Without mind wandering, we would be stuck in the moment”

Why do our minds wander? Why have our brains and minds developed the capacity to ‘decouple’ from the environment into a series of thoughts that are completely unrelated to the situation in hand?

“People say it is unintentional and they get upset because they don’t want it to happen but primarily what it is doing is allowing people to think about things they can’t see. It has a very important role in allowing us to see the ‘big picture’,” says Dr Smallwood.

“Without mind wandering, we would be stuck in the moment. We would never be able to escape the tedium of a traffic jam or a long meeting. Our lives would be one-dimensional, lacking colour, ambition and insight.”

New research project

Dr Smallwood has spent over 15 years studying mind wandering with some of the world’s top psychologists and neuroscientists. Now he aims to uncover new insights in a major £1.3 million international research project, funded by the European Research Council. The study begins in early 2016.

“One of the things we are interested in is how the brain gets its independence from the outside environment. The neurological process involved in mind wandering has this peculiarity where it allows the mind to separate us from our environment.

“We test this by asking people to stare at a cross on a computer screen. It’s hard to do this for any length of time without your mind wandering. The image doesn’t change, but there is a change in the way the brain organises itself when it starts wandering. We’re interested in how the visual and cognitive systems get pulled apart.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ON1yunvCDBc

An MRI scan shows changes in brain activity as it moves from a resting state to mind wandering.

MRI scans

MRI scans show distinct changes in the neural activity of the brain during mind wandering. But while it is possible to track the progress of wandering neurons on a scan - it is more difficult to pin down the nature and extent of the phenomenon.

“People often don’t even know when it happens or when it begins and ends. Interrupting someone to ask what they’re thinking interrupts the process you are trying to measure,” says Dr Smallwood.

Also, it is a state of mind which generates both positive and negative outcomes. The positive outcomes are the ‘Eureka’ moments when our thoughts go elsewhere and in the process, we come up with an imaginative solution to a tricky problem.

The downside is having wandering thoughts at critical moments, like driving a train or using a chainsaw. Also, Dr Smallwood says too much introspective mind wandering and rumination can be bad for our mental health. It is also at odds with mindfulness therapies which encourage us to focus on the here and now.

But despite the negatives, Dr Smallwood says that overall, we benefit: “It is a vehicle that allows us to explore our lives. If our lives are not very good, then exploration doesn’t necessarily make us very happy. It’s unclear to me if that’s the fault of the exploration or the fault of the circumstances that create the unhappy life.”

Social media

The rise of social media and digital communication also brings important new challenges for our absent minds.

“Now, I don’t have to wonder what a friend is doing, I go on Facebook. It’s almost as if we have invented technologies that serve the same function as mind wandering.”

As we age, our minds wander less. “Many important cognitive capacities diminish with age so the fact that mind wandering also reduces suggests that this phenomenon may be related to something important. So far, it is only an observation and we’re trying to tease apart the reasons for this,” says Dr Smallwood.

“What we would like is a model to help us understand how and why it happens. It’s a gatekeeper to a better understanding of many mental health problems and the development of original thought. But the fundamental puzzle is improving our understanding of why our brains wander.”

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Dr Jonathan Smallwood

Research interests in the cognitive neuroscience of self-generated thought

Publications

- Mind your thoughts: associations between self-generated thoughts and stress-induced and baseline levels of cortisol and alpha-amylase is published in Biological Psychology

- On the relation of mind wandering and ADHD symptomatology is published in Psychonomic Bulletin and Review

Visit the Department

Explore more research

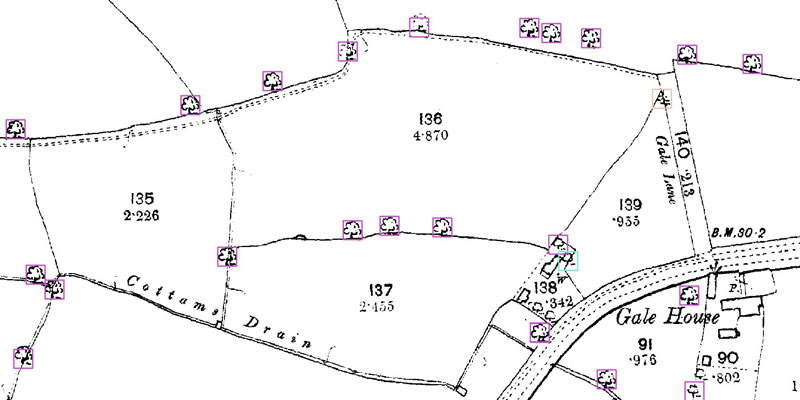

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.