How we cast new light on Britain's oldest Mesolithic art

Posted on 19 July 2016

Our archaeologists combined forces with experts across the University to bring the story of an 11,000 year-old shale pendant to life.

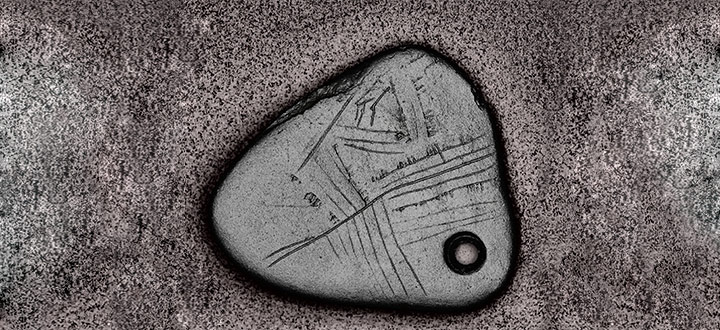

An enhanced scan image showing engravings on the Star Carr pendant. Credit: Internet Archaeology

Without collaboration across our departments...we would never have been able to discover so much about the pendant”

An 11,000 year old pendant, thought to be the earliest known Mesolithic art in Britain, can now be printed in 3D, explored online and viewed globally, thanks to collaboration across our departments.

The pendant, discovered in sediment at the Early Mesolithic site at Star Carr in North Yorkshire, was uncovered by archaeologists from the Universities of York, Manchester and Chester.

Crafted from a single piece of shale, the plectrum-shaped artefact features a series of lines which archaeologists believe may represent a tree, a map, a leaf or even tally marks.

The research was led by archaeologists. But collaboration with experts using the latest scanning techniques in the School of Physics, Engineering and Technology, Hull York Medical School (HYMS) and the Centre for Digital Heritage cast new light on the meaning and significance of the precious find.

Award

The project recently triumphed at the British Archaeological Awards when the research picked up the Best Archaeological Innovation Award.

Professor Nicky Milner, of the Department of Archaeology at York, who led the research, said: “By integrating a broad variety of scientific and imaging techniques to study the pendant, we have developed an in-depth understanding of its likely source, production, method of engraving, and its depositional context.”

The latest imaging methods were used to trace the direction of the lines, to understand their relationship to each other and the line order.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uzh4qZzKYug

A 3D scan of the pendant created at Hull York Medical School

Researchers from the Centre for Anatomical and Human Sciences at Hull York Medical School (HYMS) scanned the pendant using white light 3D surface scanning and scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

“This was useful for analysing the lines but it also meant that 3D print outs of the pendant could be made,” said Professor Milner.

“This has significant potential in the future - it means for instance, that teachers or museum educators could print out copies for children to annotate themselves. It makes what is a very rare object, become physically accessible to anyone in the world.”

In York’s Centre for Digital Heritage, researchers used reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) - a form of computational photography – to produce a set of photographs of the pendant. Using software called RTI builder, the photographs were combined to generate an interactive image.

Professor Milner said: “This technique is a fantastic tool for making a rare artefact accessible. People can explore the pendant by zooming in and out and changing the light source so you can see it in great detail. It is interactive so again is great for teaching purposes.

“When the pendant was first uncovered the lines were barely visible but using these digital imaging techniques it has been possible to examine them in detail and determine the style of engraving as well as the order in which the lines might have been made.”

Residue analyses

Researchers from our School of Physics, Engineering and Technology and Department of Archaeology also carried out microwear and residue analyses on the pendant using Raman microscopy - allowing high magnification visualisation of the pendant. They looked at whether the pendant showed signs that it had been strung or worn, and whether the lines had been made more visible through the application of pigments.

One possibility is that the pendant belonged to a shaman. Headdresses made out of red deer antlers found close to the pendant are similar to those used by shamans in the past by some Siberian groups, and it is possible that shamans were present at Star Carr.

“We can only guess what the engravings mean but engraved amber pendants found in Denmark have been interpreted as amulets used for spiritual personal protection,” said Professor Milner.

She added: “Without collaboration across our departments, and the broad spectrum of scientific analyses applied to this object, we would never have been able to discover so much about the pendant and make it accessible to people worldwide.”

This research is part of a five-year project supported by the European Research Council, Historic England and the Vale of Pickering Research Trust

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Professor Nicky Milner

Research interests in the Mesolithic period and the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition

Discover the details

A unique engraved shale pendant from the site of Star Carr: the oldest Mesolithic art in Britain is published in open access in Internet Archaeology

Watch this video about the discovery of the Mesolithic shale pendant

Find out more about York’s success at the 2016 British Archaeological awards

Explore more research

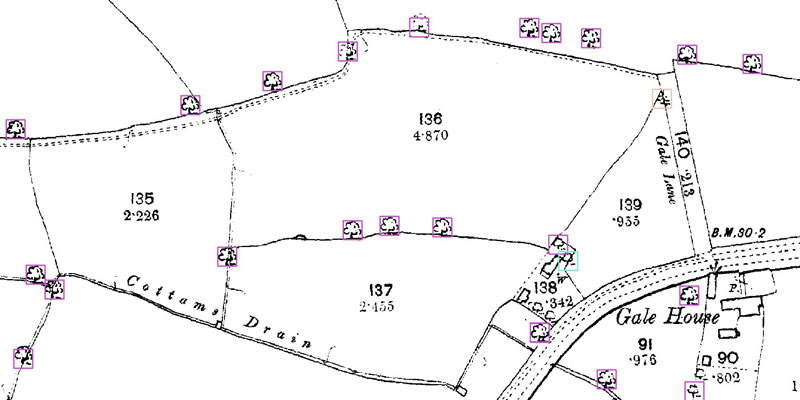

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.