Engage 2017

'Engage' is an annual conference organised by the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE) which attracts public engagement practitioners from across the UK, Ireland and further afield both inside academia and outside, including in the health, third and cultural sectors. CFH Project Manager, Philip Kerrigan attended this year’s meeting which was held 6-7 December in Bristol.

At the Conference a clear message was delivered from the Wellcome Trust, RCUK, HEFCE and individual university leaders that universities need to engage better with the general public and particularly those segments of the public who have little trust in and feel alienated from the Academy.

It was acknowledged that within the last year and a half there has been an increase in expressions of mistrust in experts and educational elites and of political movements e.g. Brexit that express scepticism towards experts. The problem is partly one of communication and perceived power relations, with universities by and large regarded by less advantaged and more impoverished sections of society as part of a remote and uncaring establishment whose workings are opaque and who might occasionally preach but does not listen.

How can universities convince the majority of the public, and especially the less advantaged, that the research they conduct is relevant to them and aimed at improving their lives? Is there a danger that society will become further polarised around the 50% who have had a university education and the 50% that have not? How can universities engage with the 50% of the current school leaving population who will not be going to university?

There is an urgent need to communicate to the widest possible public what research is and the direct value it can have to them. Universities need to be transparent about the uncertain and provisional nature of research - that frequently it delivers more new questions than answers. In an age of increasingly multiplying and open data, universities need to work hard (alongside other research bodies) to convince the public that they are reliable sources of evidence-based information.

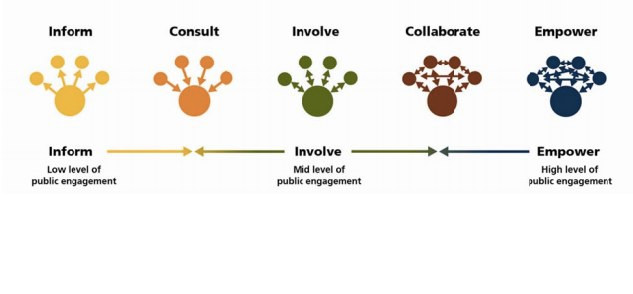

In order to do this universities need to adopt a less patriarchal and more egalitarian attitude, to position themselves not so much as curators of expertise and knowledge by historic entitlement as partners with the public in a joint venture to improve quality of life, advance social justice and reduce economic and political inequalities. The key to successful co-production is to foster a sense of common purpose and mutual respect for each other’s experience and understanding and carefully avoiding perpetuating any hierarchies of knowledge and power. This includes giving greater recognition of the value of expertise by experience that the public can have.

This is already happening in the area of PPI or Patient and Public Involvement in Research spearheaded by groups including INVOLVE and health charities. If the public is able to feel a sense of shared ownership of the research agenda then they are much more likely to be invested in its success.

There was equally agreement that research produced in consultation or co-produced with the public or the patient as end user is often more fit for purpose as better attuned to the specific needs and social, cultural and educational norms of the population.

A commonly agreed way of securing broader public buy-in was for universities to focus on engaging their local communities and to act as ‘anchor institutions’ that through their existing local economic influence, reserves of expertise and research capacity help propel a local ‘moral economy’ that looks beyond merely economic benefit to the widest social benefit and the interests of the disadvantaged and marginalised.

Equally in their communications to the wider public universities need, over and above demonstrating their international standing and kudos, to present themselves as receptive to and driven by the concerns of those who ultimately pay for a large amount of the research they perform [they won’t care how much you know until they know how much you care]. They must articulate better what they are doing and what they have successfully done to improve the lives of ‘everyday working people’.