Book recommendations to help understand a complex world

Postdoctoral Research Associate Tadhg Carroll discusses two popular science books that help unpick data driven claims, and shows why they're useful for getting a handle on LCAB’s field of research.

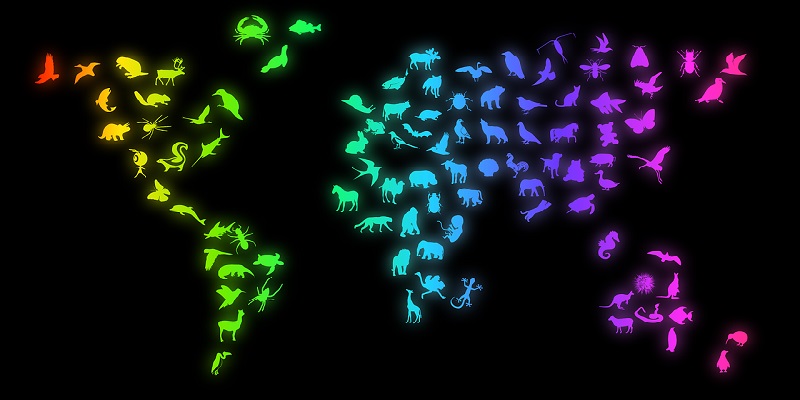

The world is complex, and there are few aspects of it more complex than the multifaceted nature of biodiversity change. In broad terms, biodiversity is a list of all the species in a given area, be that your garden or the planet, indexed by the abundance of each of these species. That is, an accounting of how many individuals of each species there are. We’ve all heard that we’re living through a biodiversity crisis, but which species are declining in abundance? How many of them have or will decline to zero and go extinct? And where? Is it all of them everywhere? (it isn’t). It’s not easy to assess information and statistical claims about biodiversity change in the Anthropocene, particularly if they’re presented short of necessary detail. Whether you’re an aspiring expert in the field, or someone who is just interested in the world around you, trying to make sense of figures and purported facts can be a tricky business. That’s why I want to recommend two excellent books which have helped me think more clearly about data-driven statistical claims.

In “How to make the world add up”, Tim Harford presents us with ten (really eleven) ‘rules’ to help understand the myriad statistical claims we encounter in everyday life. The rules span from “Avoid premature enumeration” to “Get the back story” and “Remember misinformation can be beautiful too”. They are delivered through a series of compelling, real world stories that inform and entertain in equal parts. This book will really help you examine the ‘facts’ you find yourself presented with, zoom in and out to look at the context, and ask yourself whether you’re letting emotions or preconceptions cloud your judgement. I listened to the audiobook version, which is read by Tim Harford himself and reminiscent of his equally interesting BBC Radio 4 programme on statistical fact checking: “More or less”.

Sir David Spiegelhalter covers similar ground in “The art of statistics”, but he tells us in more detail how particular methods of statistical science are used to learn from data. Also, how they can be misused. Perhaps more importantly, he shows us how best to communicate statistical claims clearly and honestly, including uncertainty and limitations. He achieves this by emphasising a problem-solving process, presenting a series of scientific questions preceding useful statistical approaches towards solving them. Some of these questions are from his own impressive career as a statistician, including how statistical science could help identify the crimes of serial killer Harold Shipman. As well as being an interesting and engaging read, this book would make a great companion text for anyone attempting to learn statistics the dry old-fashioned way.

How might we apply some of the of the wisdom of these authors to aid our thinking about Anthropocene biodiversity trends? Tim Harford encourages us to ask: is this a big number? We might ask, is the loss of three billion birds in North America over 48 years a big number? Obviously yes, it’s huge. But when we hear that there are three billion birds fewer, would we be filled with the same sense of dread we might feel if we knew that the majority of birds lost may have been from common species with ‘artificially’ high population sizes due to human association? Probably. But it’s certainly worth digging into the details and getting the back story to deepen our understanding. We could ask similar questions of the apocalyptic “Insect Armageddon” stories trending in recent years. Surely the global syntheses which provoked such a stir were massively comprehensive, covering vast representative areas and looking at all the evidence for both insect declines and increases? Think again.

The lack of robust, representative data underlying the “Insect Armageddon” narrative, and others like it, gets at one of the key difficulties in interpreting contemporary biodiversity trends. In rule eight, Tim Harford tells us: “Don’t take the statistical bedrock for granted”. He makes an extremely convincing case for the importance of independent statistical agencies and statisticians to collect, analyse and interpret the vast swathes of data that give us a clearer and deeper understanding of the world. Of course, this requires adequate funding. But it’s money well spent. Unfortunately, it’s not money that’s spent widely on biodiversity monitoring. While there have been laudable efforts to compile and make available the data that’s out there (e.g. BioTIME, PREDICTS), the data that is out there is biased in it’s geographic and taxonomic composition (Rule six: “Ask who is missing”). To regularly compile population data on a single species, Homo sapiens, is a difficult, labour intensive and expensive endeavour, but one that’s incredibly valuable. Now imagine scaling that up to the many millions of populations of the other species on the planet, many of which are cryptic and difficult to find. Ad hoc data collected by interested naturalists and a smattering of academics is not enough. We need a move towards stratified random sampling of the planet to overcome the biases entailed in the best biodiversity data we currently have.

The most useful takeaway from the two books might be to heed advice to ask yourself whether you really understand a claim being made. When I hear that biodiversity is in decline, I semi-consciously envisage a vague, amorphous, brownish green blob, somehow on a downwards trajectory. I’m sure these weird specifics are just me, but think about it, what do you imagine? A lonely polar bear floating on a melting iceberg? A panic-stricken horde of jungle critters fleeing a bulldozer through the treeline? Whatever it is, it’s probably far simpler than the complex reality. While many species are in decline – some unfortunately on a terminal trajectory – others are on the up, thriving in human-modified landscapes. Others still are declining in some places and increasing in population size in others. Getting a handle on these complex dynamics will likely be a major challenge of our field for decades to come. Sometimes just pausing to realise that you don’t fully understand a scientific or statistical claim, or the real-world phenomena underlying it, is the most valuable insight available. It might serve as a better platform from which to dig deeper and find out more than assuming you’ve grasped it and moving on.

Related links

Find out more about Tadhg Carroll's research.

Related links

Find out more about Tadhg Carroll's research.