The Green Climate Fund Is Not Doing Enough to Support Just Transitions in the Global South

In the lead up to COP26, IGDC Postdoctoral Research Associate, Dr Jessica Omukuti, examines if enough has been done by The Green Climate Fund to facilitate just transitions through its funded projects for global South countries.

.jpg)

Image: Green Climate Fund rally by Friends of the Earth International via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The focus on zero emissions and adaptation and resilience in the run-up to COP26 has elevated discussions on how countries, firms, and communities should go about transitioning to zero-carbon climate-resilient economies. Yet, discussions on transitions have historically overlooked concerns. This means that while the concept of just transition is central to COP26 themes, conversations informing these discussions have previously been “Northern centric” and have insufficiently allowed for alternative perspectives and approaches more attuned to the economic and social realities of the global South. In this think piece, I explore why the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which is the main finance instrument of the Paris Agreement, has been unable to contribute to just transitions in a way that reflects the adaptation and mitigation needs of countries in the global South.

What do just transitions mean for developing countries?

Due to the disproportionately adverse effects of climate change risks for communities in the global South just transitions for countries in the global South requires the following:

- Equal investments in adaptation and mitigation in alignment with the Paris Agreement,

- Ensuring that the current and future costs and benefits of low-carbon climate-resilient development are distributed equitably among groups, with particular attention paid to those who are particularly affected by these climate change risks.

The first round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted by developing countries strongly reflected the nature of just transitions in the global South. Tanzania’s NDC emphasized the need for adaptation to be considered alongside mitigation. This was re-emphasized in the 2020 revised NDC submissions by global South countries. Overall, the submissions reflected stronger ambition for mitigation and adaptation. These ambitions reflect increased momentum towards transitions to low-carbon climate-resilient development.

While there are challenges to achieving these transitions in the global South, such as political economy factors which limit the capacity to achieve these goals the achievement of the ambition reflected in these NDCs will strongly depend on the availability of climate finance and technology.

Enters the Green Climate Fund

The Green Climate Fund (GCF) was launched in 2010 with the mandate of accelerating developing countries’ transitions to a low-carbon climate-resilient economies in alignment with the Paris Agreement goals. Since its operationalization in 2015, the GCF has received over US$20.3 billion in pledges from developed country contributors making it the largest dedicated climate fund. The GCF leverages this comparative advantage and uses innovative financing instruments such as loans, equity and guarantees to de-risk and attract private sector investments into low-carbon transitions in the global South.

Image: Launch of COP26 Private Finance Agenda by COP26 President Alok Sharma by Bank of England, via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Yet, while the number of approved projects for both adaptation and mitigation, as well as the amount of committed and disbursed GCF climate finance have grown, there still exist gaps in relation to how well the GCF supports just transitions in the global South.

Bias in allocation of resources

First, the GCF is investing less in adaptation as compared to mitigation, which is threatening just transitions. As of December 2020, the GCF had invested US$ 7.3 billion into adaptation and mitigation projects and had attracted US$ 16.1 billion in co-financing. Despite a pre-existing commitment to an equal balance in investments between adaptation and mitigation, recent evaluations of the GCF have found that the GCF is investing more in mitigation as compared to adaptation. Despite the GCF claiming to have achieved an equal split in grant allocation between adaptation and mitigation, as of early 2021, its total mitigation investments surpassed investment in adaptation by US$ 1.97 billion.

Recognizing the need for additional funding, the GCF aims to catalyse additional investments in adaptation and mitigation by deploying innovative financial instruments such as loans, equity and guarantees. However, these instruments have little effect on adaptation finance. Direct access accredited entities, which are usually national and regional institutions which are accredited to receive project funding from the GCF, have limited experience using these non-grant based financial instruments to catalyse additional funding for adaptation. Consequently, evaluations also show that adaptation projects are leveraging less co-financing as compared to mitigation.

This reflects a lack of strong commitment from the GCF on increasing investments in adaptation. This is worrying, especially as global donor and private sector interest towards mitigation continues to increase with limited evidence of similar enthusiasm for adaptation and resilience.

Second, investments are overlooking outcomes that benefit poor communities and groups. The bias in allocation of resources in favour of mitigation has translated into more investments in GCF’s four results areas that are linked to climate change mitigation outcomes. Results areas enable the GCF and its partners to ensure that project development and funding allocations are strategic and in alignment with country needs.

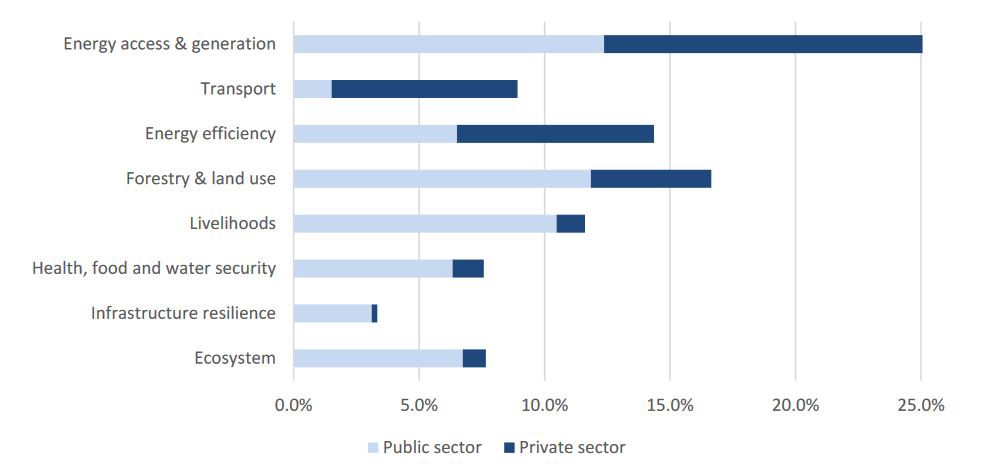

Yet, recent reports show that investments are overlooking result areas that benefit particularly poor groups in countries in the global South. The GCF’s reports to COP24 and COP25 indicated that investments tend to go to mitigation results areas on energy access and generation, and forestry and land use. Other results areas, such as ecosystems and ecosystem services and the development of resilient infrastructure and low emissions transport, attract comparatively less investments.

The results areas that receive less financing are critical for adaptation, particularly for vulnerable groups in the global South. A good example is ecosystem services which are important for rural communities in managing climate risks. Investments in low emissions transport also benefit low-income urban households and can be expanded to rural communities that are underserved by public transport. The exclusion of these social groups makes the emerging GCF-funded transitions in these countries unjust.

Image: GCF pipeline in 2019 by result areas. First published by the Green Climate Fund

Inadequate safeguards to protect communities from exploitative practices

Third, the GCF has gaps in its environmental and social safeguards (ESS), which is a major barrier for just transitions in the global South. GCF’s ESS are ‘a set of management processes and procedures that allow GCF to identify, analyse, avoid, minimize, and mitigate any potential adverse environmental and social impacts of GCF’s funded activities, to maximize environmental and social benefits, and to improve the environmental and social performance of GCF and its activities consistently over time’.

GCF’s accredited entities inadequately integrate, implement and monitor ESS considerations. Additionally, the GCF fails to ensure compliance with these safeguards during project implementation. Hence, co-benefits of investments in adaptation and mitigation are not fully explored and leveraged. For instance, inadequate compliance can result in projects that overlook human rights or the protection of indigenous people.

The absence of these safeguards in low-carbon transitions generate injustices. It is therefore difficult to verify the GCF’s claims that its funded projects are not (re)creating or (re)distributing harm from climate change and climate change adaptation and mitigation projects.

What happens at and after COP26?

COP26 will see discussions on how to increase ambitions for adaptation and mitigation to accelerate transitions towards low-carbon, climate-resilient development. The GCF has a key role to play in supporting countries in the global South to achieve these targets.

The GCF, through its funded projects, is failing to support countries in the global South to achieve just transitions. This matters for whether and how we achieve climate action goals set out in the Paris Agreement. At and after COP26, it will be important to reconsider how the GCF’s structure should be improved to ensure that its funded projects deliver just transitions to a low-carbon, climate-resilient development. The international climate change community should also reflect on how existing accountability mechanisms be used to enhance GCF’s contribution towards just transitions.

This article by Jessica Omukuti was written for and originally published on Medium and is republished here with permission.

Contact us

Interdisciplinary Global Development Centre

igdc@york.ac.uk

01904 323716

Department of Politics and International Relations, University of York, Heslington, York, YO10 5DD, UK

Twitter

Contact us

Interdisciplinary Global Development Centre

igdc@york.ac.uk

01904 323716

Department of Politics and International Relations, University of York, Heslington, York, YO10 5DD, UK

Twitter