A case for the pickled larynx

Anthony Rooley

We don’t have a pickled larynx from Dowland’s day – or Henry Purcell’s either; but we do have various fragments of different musical instruments from earlier times – and occasional surviving complete instruments. It is the study of these surviving artefacts that has kept alive the ‘early music movement’ for these last 40 years, and it is the fruits of these studies, applied research and skilled craftsmanship along with dedicated application of re-discovered fingerings and playing techniques that forms the basis of so much excellent live performance and recording of instrumental music from past centuries. But a recording of Handel’s dramatic cantata, Apollo and Daphne, I heard recently underlined the dilemma that has brought this present conference into being. Stylish and aware instrumental contributions that probably would have delighted Handel himself were paired with vocal contributions that were grossly inappropriate, and an assault to the ears of any Age – Handel’s, or our own.

It is the ‘explosion’ of interest in organology that creates the common sight in Basel, Switzerland (intensified as one approaches the compound of the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis) of dedicated lutenists or gambists walking, or cycling, to their next rehearsal with 2, 3 or more instruments strapped around their bodies – looking for all the world like over-burdened tortoises, or some badly abused donkey from Bulgaria. The alert, aware, sensitive lutenist today must own 8 or 9 different instruments (I have upward of 12 at last count) in order to cover the repertoire encountered in an average week’s rehearsing – in anything like an appropriate manner.

The singers can count themselves lucky – just the one piece of equipment that travels light – with them wherever they go, and this equipment has changed little over the last 1000 years and more. Diet has made us taller; abuse has increased obesity; hormonal changes are on the increase – but the throat, larynx, tongue, teeth, lips, palate and all the bits that make up vocalizing would appear, in essence, to be roughly the same now as that of a mendicant friar of Hildegard’s time. And yet this very instrument, common to all humanity, across time, geography, and vastly varying cultures is so infinitely flexible as to allow the creation of sounds, timbres and colours of such diversity as Japanese ‘Noh-drama’, Bulgarian Funeral Ululation, Aboriginal Gossip-songs, Frank Sinatra, Dame Nelly Melba, Mario Lanza, and Sting.

It is now a fact, and used in the ‘War Against Terrorism’, that the individual voice has an imprint as unique as fingerprints, the iris, and the very DNA of each of every one of us... and apparently more speedily identified in certain contexts than some of these features. With such diversity available, how can we begin to approach any particular repertoire with real integrity? How do we create appropriate performing, presentation parameters that take in ‘Historical Awareness’, ‘Composers’ Expectations’, ‘Poets’ Fancy’ – and act as a suitable translation for an audience today?

I suggest we look at these matters

all from an historical point of view, as far as our understanding allows. For

example, we know that ‘performance’ in the 16th century consisted of

three balanced energies, known most readily under their Italian labels: decoro, sprezzatura, grazia. Precisely

defining these energies is not the purpose here, but assigning to decoro all those things that can be

studied, prepared in advance, practised before the actual performance will be

enough for now – and that wholly accurate from a Renaissance understanding. For

the singer, what is appropriate decoro

in terms of relevant vocal techniques, colours, manners? What part of the

individual needs activating to access a ‘hot-line’ to Monteverdi, for example?

It is nothing fundamentally to do

with ‘larynx’, ‘tongue’, ‘palate’, ‘epiglottis’ – or any of the other bits of

physical apparatus. It is entirely to do with the mind, and how the mind is

composed, regulated and exercised. How has the ‘mind-space’ changed over these

many centuries, and how has our relationship to this interior ‘mindscape’

changed? Do we access the mind in ways differing from our forbears? And how

different are our expectations? When I listen to a singer, I hear not only

beauty of tone, clarity of diction, appropriate passion, I hear the mind behind

the voice – the intelligence, the alertness, the discrimination, the awareness,

the understanding, the fantasy, the imagination. These features move me at

least as much as the vocality. These same elements have fired the response of

listeners to singers over many centuries – they are not new – they are the

natural outcome of the allure of ‘beauty and intelligence of voice’. But

‘mind-space’, of its nature is difficult to define and therefore to study, to

develop and to mature. What techniques can we adopt to work with precision and

intellectual rigour in a way conducive to singers’ understanding and

application in practice? Psycho-babble is the last thing needed, pseudo-jargon

is likewise something to avoid, and the falling back on ‘received wisdom’ from

a previous generation of uncritical singing teaching is a pitfall with dire

consequences (even though all these are frequently met with...).

By searching history for examples,

by looking closely at source materials with a fresh eye, by going beyond the

restricting confines of the usual reference points habitually associated with

singing training it is possible to define certain essential strands, some of

which have almost completely dropped out of general social awareness, and

educational parameters that are the norm today. Think of ‘elocution’, for

example: until the early 1950s almost every educated person would have had at

least an introduction to elocution, and many young ladies were given a most

thorough grounding. But today, there are a tiny handful of university

professors – mostly in the US – studying closely the principles of elocution.

It’s not dead yet – but damned near close to passing away. Yet it is the very

heart of our vocal culture, both spoken and sung. The pace-making work of Robert

Toft, and a very small band of others, has raised awareness but slowly – partly

because of the innate conservative nature of voice-teaching, and the safety in

the familiarity of immediately received attitudes and habits (and suspicion of

anything ‘new’ – even though the ‘new’ in this case may actually be ‘old’,

‘original’ and ‘authentic’).

I run a seminar class at the Schola Cantorum in Basel called simply ‘Performance and Repertoire’ – a title so broad it allows me to do anything I wish. The express purpose is to help develop a new practical philosophy of performance, based on historic enquiry and on my own extensive performance experience with the ‘Consort of Musicke’. Typically we take a strand, an idea, a theme from around a specific repertoire – both vocal and instrumental – and broach some of the concepts in a journey of discovery, and apply them to work in hand. Taking ‘elocution’ as one such strand, it immediately leads to others: the subject of ‘Rhetoric’ comes forward quickly, and that leads to embracing ‘Oratory’, ‘Gesture’, ‘Stance’, ‘Modulation of Voice’, ‘Performance Attitudes’, ‘Expressing the Passions’ – and how all these strands weave together in wonderful complexity, and vary with every decade, every country, in the theatre, or chamber, or church – such that there is certainly a continuity of tradition based on the ‘Ancients’, but a tradition that re-manifests itself in endless variety and subtlety. For a precise example: when we discovered the three Aristotelian ‘Truths’ and how absolutely central and essential they were to vocal performance particularly, we were ‘elevated in an ecstatic transport of Divine Frenzy’ (to quote one auditor’s response to a performance in the early 16th century).

Logos, Pathos, Ethos

Of these three, the third, ‘Ethos’ is the most vital in this trinity of vitalities. ‘Logos’: truth to the ‘Word’; ‘Pathos’: truth to the ‘Passion’; ‘Ethos’: truth to ‘Oneself’ – and this awareness lies at the very heart of all oratory – and all song performance has oratory at its very core. If your song does not persuade your listeners to the logos, pathos and ethos– the three essential truths behind the particular song – then it is time hang up (or pickle) your larynx…

I would like to introduce you to some of the discoveries we have made in the Seminar Class, by way of ‘brochures’ made as hand-outs.1 Discovering the ‘brochure’ as a teaching tool has been a revelatory experience for me –a well-made brochure can first raise curiosity, then desire – before any real serious study can be expected. If, by the end of this paper I have raised your curiosity, and perhaps tickled your desire, then the rest of the journey is just a matter of time – you are on the way!

The first ‘brochure’ reveals just some of the publications in England, from the earliest printing, through the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, with merely a smattering of 19th-century publications too vast other than to intimate what is to be found. The insides of these volumes, whilst tough going sometimes because of denseness of prose, are every bit as exciting as the displayed graphics of the title-pages.2

The brochure also reproduces the final pages of William Newton’s The Elements of Singing, published in London in the 1850s. The body of the book covers admirably the approach to singing as seen from a gentleman-teacher from the Provinces, but he chooses to close with a revealing exploration of the just expression of ‘The Passions’ either by the spoken or sung voice – almost all of this literature elides singing and speaking in this way, so that clearly it was thought the orator should learn from the singer, and vice versa.

Newton sums up his previous pages thus:

Figure 1: from William Newton’s The Elements of Singing (London, c.1850):

He then proceeds to intabulate a thorough list of the variety of passions and their just and dramatic expression. The third and final part of the first handout shows the wider application of ‘elocutory matters’, as understood in the early 19th century.3

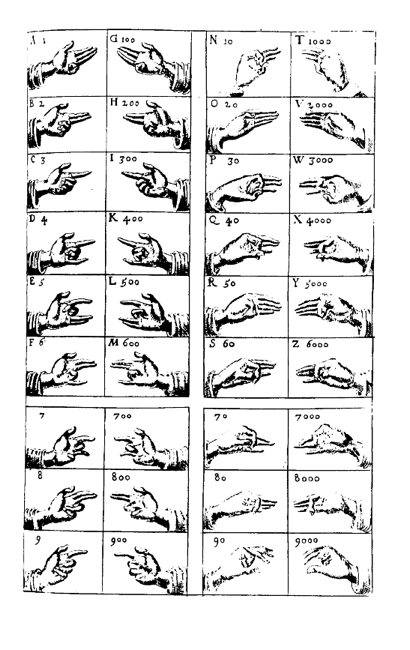

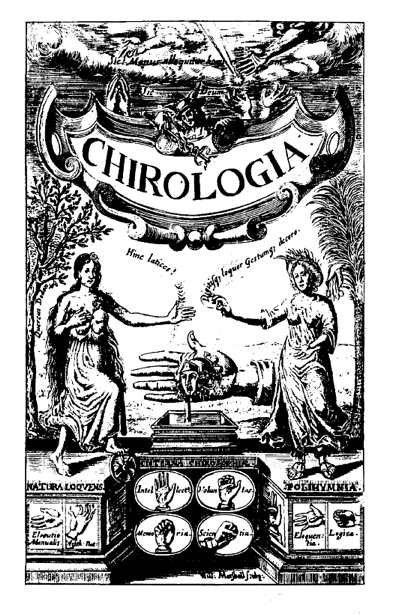

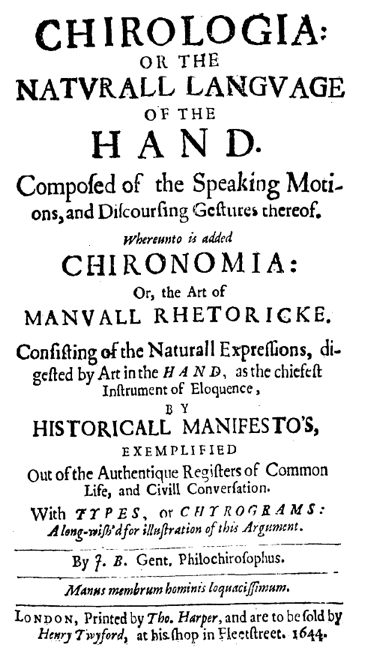

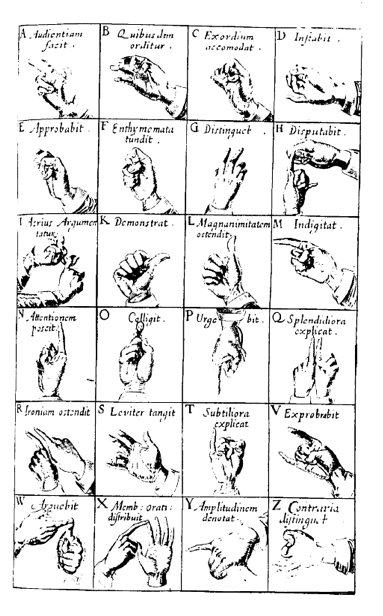

My second brochure goes deeper into ‘gesture’ as a topic for thorough study, analysis and application. The first part makes a quick resume of the well-known sources: John Bulwer, from 1644, and his helpful cartouches of hand gestures (suitable for church, theatre or at the Bar:

Figure 2: pages from John Bulwer’s Chironomia (London, 1644):

Bulwer was codifying existing practice, not establishing new principles, and with care much of what he outlines can be applied back to the previous 50 years at least.

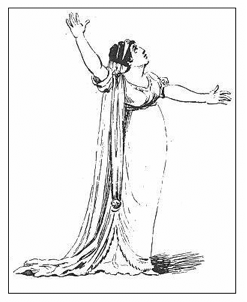

From 150 years later, the immensely valuable work of Gilbert Austin, from 1806 – so clear, so detailed, yet essentially of the same long tradition as Bulwer. Only the methodology is nearer to our own time, more specific, more scientific:

Figure 3: pages from Gilbert Austin’s Chironomia (London, 1806):

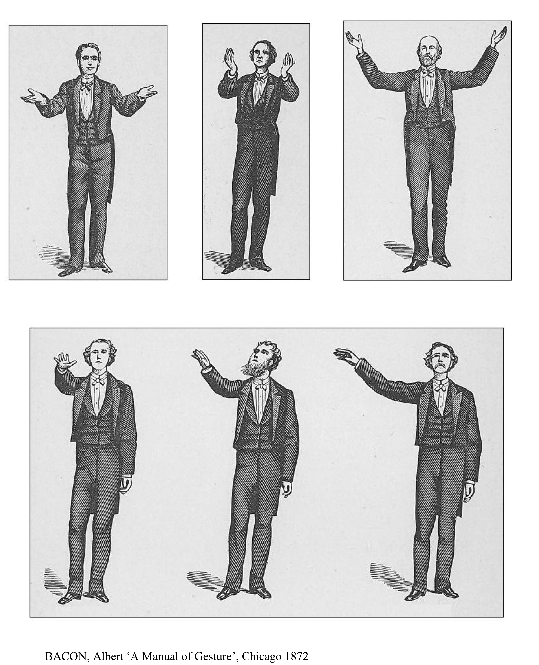

Finally, there is a page from Albert Bacon’s ‘A Manual of Gesture’, Chicago, 1872 – with illustrations almost photographic in their effect. Whilst there are many differences – of style, manner, emphasis – these few pages reveal a living tradition of about 300 years, and of inestimable value to the singer who wishes to adopt a mode of vocality and presentation closer to all the composers active in that time-span:

Figure 4: from Albert Bacon’s A Manual of Gesture (Chicago, 1872):

But some of you will cavil and claim I make too broad a sweep; I am not saying these 300 years can be treated the same, but believe the tradition was an uninterrupted one whilst enjoying shifts and changes of emphasis. Bacon was closer to Bulwer than we are to Bacon, and that is only a time-span of just 100 years. After a century of two utterly devastating World Wars, and the unprecedented rise of mass-media entertainment, followed by the effects of digitization, and the on-going ‘War-on-Terror’, any sense of continuity of tradition has gone the way of the Dodo.

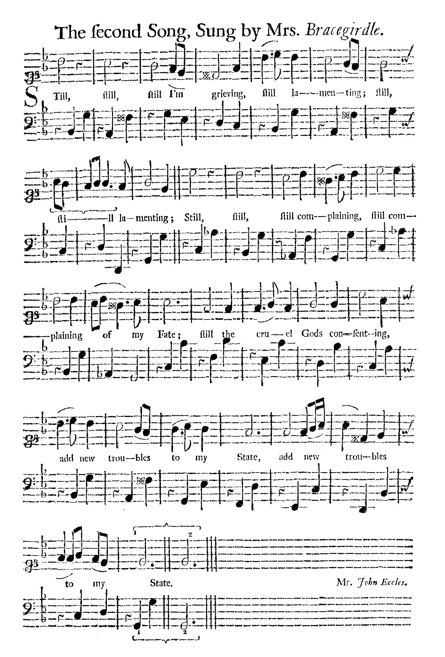

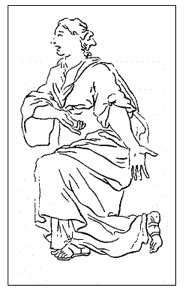

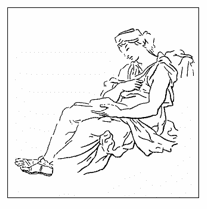

The final part of the second brochure focuses precisely on one single song, of one of the extraordinary singing actress known to Henry Purcell. Here I apply appropriate gesture patterns to a brief, artful song composed especially for her.

But first a word about her, for

she may not be a familiar name to all. Mistress Anne Bracegirdle: born in Northamptonshire,

to a family of modest means. Her father was a ‘brace-girdler’, that is he

attended pairs of horses that were being refreshed to make the energetic

journey from London to York to Edinburgh. Northampton was the first day’s

stopping point out of London. By the time she was aged 6, it was already clear

she had a performing ability, and a very sweet voice. She was moved to London

at this tender age, to live in the house of Mr. Thomas Betterton, and his wife

Mary – and therefore plunged into the very heart of London music-theatre. They

brought her up with care – a precocious child, immensely talented – and

nurtured her through childhood and early adolescence. It was to be her

theatrical fate to be ‘the Virgin’, ever-green, pure, a tease, the very

coquette... and this she played brilliantly, even though the theatre was famed

for whores, vamps and prostitutes. ‘Bracey’, as she was familiarly known, lived

a complex private life: she was loved by the poet William Congreve, and John

Eccles, her personal composer, and there might possibly have been a

‘love-triangle’ with these two men who openly adored her. But then, the greater

part of the London theatre scene was in love with her too – but ever the

virgin!

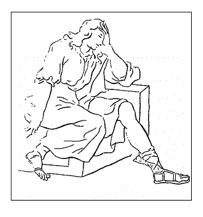

She learned well from Betterton’s training: he advocated that any worthwhile actor would use not less than 6 musical tones in their recitation. He based this on the writings of the ancient Roman writer Julius Pollux, who tabulated the 20 different bad uses of the speaking/singing voice, and also the 20 good uses (Gilbert Austin called on the same source 100 years later). This is a degree of ululation perhaps like that of Sir John Gielgud, one of the last of ‘the old school’ (that is, pre television theatrical training). Bracegirdle excelled in this ululating style, and moved from speech to song, and back again with ease. Roles were created for her that explored this fluid transition, but she also moved exquisitely: she appeared on the stage as if from nowhere, to a gasp – and then when she made her exit, the audience gasped because their idol was gone. Her songs were at the creative edge of music-theatre – mad-songs, seduction songs, and songs of guileful simplicity. I present one here: ‘Still I’m grieving’, and atomize it to show a possible rendering of it according to what Bracegirdle had learned from Betterton and Pollux.

Figure 5: ‘Stil I’m Grieving’ John Eccles:

The song turns on the word ‘still’, in its several possible meanings, and explores them all, the word recurring 22 times (with the given repeats of the A and B sections). I propose that each repetition of ‘still’ requires a small shift of posture and gesture – a mannerist response to the word itself – underlining the mannerist verse. Attached I give a suggested sequence of what those small posture/gesture movements might be, drawn from the sources within the tradition. I presented this material to the Seminar Class, with a student singer making the shifts and turns, and then asked the entire group (perhaps 18 people) all to respond in like manner. The whole gathering found ‘stillness’ between each movement, and discovered that surrounding all gestural and posture movements is stillness and rest. The intensity of this simple song was profound, and a lesson was learned. Mistress Anne Bracegirdle moved amongst us, with her ‘passionate postures’, and our group realization of the value of close historical enquiry was affirmed.

Figure 6: appropriate gestures from contemporary sources:4

Anthony Rooley

Anthony Rooley is a British lutenist and scholar. He founded in 1969 and directs the early music ensemble the Consort of Musicke, which continues to be one of the chief vehicles for his inspiration, among many other activities and interests. He has recorded extensively and continues to perform solo and duo repertoire with sopranos Evelyn Tubb and Emma Kirkby. Anthony was appointed York Early Music Festival Vice President in 2008. He continues regular work as a Visiting Professor at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, where he is Director of AVES – Advanced Vocal Ensemble Studies, a new Masters Programme created to give young singers a practical awareness of the repertoire. Most recently he has been appointed a Visiting Professor at the Orpheus Institute, Ghent, under the heading ‘Developing a Practical Philosophy of Performance’. In 2003, 2005 and 2007 he undertook four-month residencies at Florida State University, holding graduate seminars and directing productions. In 2003 this included a fully staged version of Semele by John Eccles; in 2005 a ‘first’ Conference on John Eccles; 2007 focused on The Passions of William Hayes.

Writing and research are of great importance, to develop and extend the repertoire; plans for the future include more time for writing. Recently, Anthony has turned to the 18th and 19th centuries, as part of his continuing project to search out the best of forgotten English music. In 2004 he directed performances, live and on CD, of the madrigals and part-songs of Robert Lucas Pearsall, and in 2005 The Passions by Handel’s contemporary and champion, William Hayes, which was revived for the Weimar Festival in 2006.

- The forgoing illustrations are all from brochures prepared for the Performance and Repertoire Seminar Class at the Schola Cantorum Basel and distributed to conference delegates.

- The brochure consisted of the title-pages of books devoted to Rhetoric, Oratory, or Elocution. Those interested in finding chapter and verse on these editions are advised to read the ‘Bibliography of Selected Primary Sources’ in Robert Toft’s two indispensable books Tune Thy Musicke to Thy Hart, The Art of Eloquent Singing in England, 1597–1622 and Heart to Heart: Expressive Singing in England, 1780–1830 where most, if not quite all examples are listed. Neither his, nor mine is complete – yet both are vast enough to prove the point: this is a tradition of primary importance to all those desirous of refining performing skills, and cannot be ignored by anyone intending to approach Dowland, Purcell, Handel, even Elgar in anything remotely approaching an authentic manner.

- This is a cartoon, a send-up of a Ladies Preparatory School, caricaturing the excesses that probably did at times exist. It is like a Monty Python Sketch, and is entitled ‘An Elegant Establishment for Young Ladies’, by Edward Francis Burney and printed around 1835. In the conference handout I highlighted some of the many fascinating scenes contained within the whole picture, and gave them ‘fanciful’ titles. There is a massive amount of information to be found here, and though this be caricature, there is much to learn about stance, posture, gesture, study, training – and Man’s abuse of Man.

- Only a representative selection from the brochure is reproduced here.