Reading between the brides: Lucrezia Vizzana’s Componimenti musicali in textual and musical context

Katrina Mitchell

In the newly-renovated chapel of the Santa Cristina convent in Bologna, Italy stand two important female saints: Saint Cristina, the convent’s special protector and Saint Mary Magdalene, a female saint closely linked to music. Four male saints comprise the rest of the chiseled company making their way up to the high altar. The two women, however, are given a place of prominence, nearest the doors, and serenely stare at one another from across the width of the church. Though the convent was known throughout Bologna for its excellent music-making, we have only one taste of the musical sounds that emanated from Santa Cristina, and one of its finest – Lucrezia Vizzana – is still today the only Bolognese nun known to have ventured into print.

In this presentation, I would like to offer a snapshot of Vizzana’s sole publication, Componimenti musicali, as well as a few diverse lenses through which one can examine its contents. We will begin with some brief biographical information about Lucrezia Vizzana and her published set of motets. Then I will suggest what I think is a significant aspect of Vizzana’s writings – the role of Mary Magdalene. Next, I would like to make a brief comparison with two of Vizzana’s contemporaries – Alessandro Grandi and Claudio Monteverdi.

Lucrezia Vizzana was born 3 July 1590 and entered the foremost musical convent in Bologna, Santa Cristina della Fondazza, along with her older sister sometime around 1598. Craig Monson, in his book Disembodied Voices: Music and Culture in an Early Modern Italian Convent, contends that it is quite probable Vizzana received her musical training from one of three aunts who were already at the convent. The most likely candidate as a musical teacher was Vizzana’s aunt Camilla Bombacci, who served at times as convent organist and earned an impressive reputation as a musician at the convent. It is also possible that Lucrezia received clandestine composition instruction from Ottavio Vernizzi, organist at San Petronio and the unauthorised maestro di musica at Santa Cristina. Vizzana’s Componimenti musicali marked the peak of artistic, musical and devotional activities at Santa Cristina della Fondazza. The convent necrology, however, reveals Vizzana’s early retirement from music due to increasingly severe illnesses and the convent’s battles with the diocese, which, according to a fellow nun ‘began because of music’. According to Vizzana’s confessor, Mauro Ruggeri, the events so disturbed Lucrezia that she eventually lost her mind. She died on 7 May 1662, exactly thirty-eight years following the death of her aunt, Flaminia Bombacci.

Her lone collection, Componimenti musicali, was produced in Venice in 1623 and dedicated to her fellow nuns at Santa Cristina. One print is housed in Bologna and one in Wrocław. The set consists of ten solo motets, eight duets, one trio, and one quartet, all with continuo. Professor Monson transcribed three solos, two duets, the trio, and the quartet. I have since transcribed the rest that, to my knowledge, have not been previously put into modern notation. Some might be familiar with Musica Secreta’s recording of all twenty motets – the only one I have found – by Deborah Roberts and her group.1

Twelve of the twenty texts come from known sources. We might assume that Vizzana composed the other eight herself. Personal piety is emphasized as a large number of motets in the collection revolve around Jesus Christ with as many as eight that seem specifically directed toward Jesus. Craig Monson reminds us that this is ‘an unusually high percentage by comparison with publication from the San Petronio... circle..., but not surprising for a community of brides of Christ’.2

A viewpoint not yet considered in Vizzana’s music is its association with Mary Magdalene. The connection between Mary Magdalene and music is noted in H. Colin Slim’s essay ‘Music and Dancing with Mary Magdalen in a Laura Vestalis’.3 Throughout Italy, several convents were dedicated to Mary Magdalene, while others placed themselves under her protection. Further, as a central figure in female monastic life, it is not surprising, that the Magdalene’s likeness is placed in an important position near the doors of the outer church at Santa Cristina della Fondazza. And perhaps most significantly, she is prominently displayed in the altar piece of the outer church in Ludovico Carracci’s Ascension. The obvious emphasis on the Magdalene is portrayed in her upward gaze when nearly every one else in the painting is focusing on Christ.

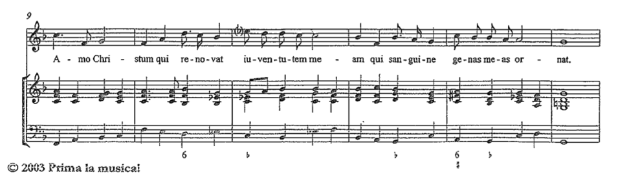

Let us now turn our attention toward comparing Vizzana’s works with those of some of her contemporaries. Examining Vizzana’s aptitude as a composer holds great potential for understanding more of the compositional tools and musical rhetoric of the day. We, in turn, will look to Alessandro Grandi for comparison. Born around ten years before Vizzana and living in the nearby town of Ferrara during the early part of his life, Grandi, with his first book of motets published in 1610, supplies a point of association for Vizzana’s motets. Grandi’s melodic imagination and creative ideas about textural contrast move the affections by the new musical means available to the early Baroque composer. His ‘O quam tu pulchra es’ is of particular interest for its use of texts from the Song of Songs. Although only one of Vizzana’s motets, ‘Sonet vox tua’, acquires its text from the Song of Songs, several in the set capture the essence of a love song. For instance, in Audio Example 1,4 ‘Praebe mihi’,the singer refers to Christ as her ‘most beloved Lord’ and employs such actions as ‘beholding’, ‘loving’, and ‘delighting’. Audio Example 2, ‘Amo Christum’ is perhaps even closer to the Song of Songs texts with its mention of bedchambers and the adornment of the betrothed. In a further connection, Grandi’s ‘Amo Christum’ includes the burgeoning Baroque styles of recitative and solo madrigal, also evident in Vizzana’s writing.

Figure 1: Beginning Baroque style in Grandi’s ‘Amo Christum’, bb. 9–14.

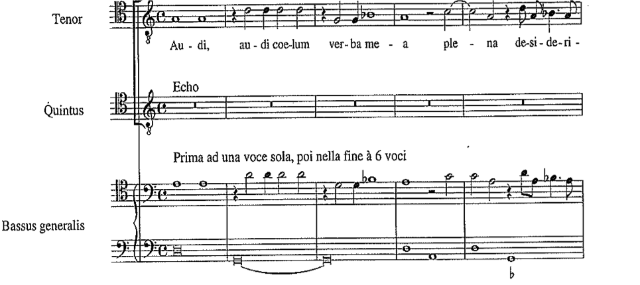

Lastly, we look to Claudio Monteverdi. Continuing with the thread of texts from the Song of Songs, we consider his motet ‘Nigra sum’ from Vespro della Beata Vergine of 1610. Monteverdi’s techniques in this motet are of particular interest when examining Vizzana’s works as his rhetorical approach from madrigal composition is transferred to his church music. Allegorical interpretations of these texts often identify the bridegroom with Christ and the role of his chosen bride. Monteverdi’s music is a particularly useful means to sort out the sensual elements of Vizzana’s motets as one traces these elements of secular music into sacred texts. Monson suggests that Vizzana was perhaps exposed to the works of Monteverdi through one of the male composers living and working in Bologna at the time (Banchieri, Vernizzi, or Porta).5 This possibility is supported by the fact that Aquilino Coppini, who worked in and around Milan, made many of Monteverdi’s most well known madrigals at this time into motets. The similarities between the writings of both come to light when one considers one of Vizzana’s favorite expressive devices – a leap from a suspended dissonance. She employs it in six of the twenty motets. Monteverdi also uses it in ‘Audi coelum’ also from the 1610 Vespers, as seen in Figures 2a and 2b.

Figure 2a: Leap from a suspended dissonance in Monteverdi’s ‘Audi coelum’ from the Vespro della Beata Vergine, bb. 1–5.

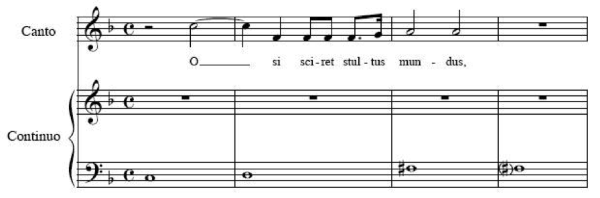

Figure 2b: Leap from suspended dissonance in Vizzana’s ‘O si sciret’, bb. 1–4.

Vizzana’s rhetorical effect, declamatory style, and handling of chromatics and dissonances place her squarely in the realm of the influences of the stile moderno.

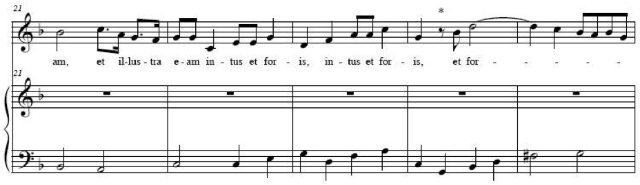

Craig Monson calls ‘Praebe mihi’ ‘an overt love song to the heavenly spouse’ – and indeed it is to the ‘most beloved, most delightful Jesus’. Its analogous use of light, a long tradition in reference to spiritual beings, provides the backdrop for one of Vizzana’s more elaborate motets. Melismas on ‘vedere’, ‘posidere’, and perhaps not surprising ‘perpetutum’ not only reveal her careful handing of the text, but also her delight in the subject matter. She describes her ‘enlighten[ing] within and without’ by way of a skilful canon between the voice and the bass as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Canon between the voice and bass in ‘Praebe mihi’, bb. 21–25.

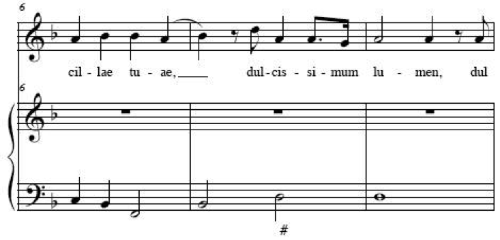

Her use of chromatic chords a third apart are also a common occurrence throughout the set and they are used here for the ‘sweet light’ of her ‘beloved Jesus’.

Figure 4: Chromatic chords a third apart, ‘Praebe mihi’, bb. 6–8.

Finally, ‘Amo Christum’ is perhaps the most explicit text in the collection with reference to being a bride of Christ. One does not often speak of bedchambers and virginity in the same sentence; in this case, however, that is exactly the point. The text can be traced back to the twelfth century, sung by nuns at their consecration ceremonies. This text would have had particular significance for the younger Vizzana, having been denied permission to participate in the ceremony due to her young age. She even padded her age by two years in the petition, stating that she was eighteen, well below the required age of twenty-five, but the request was still denied. Her sister was also under the required age of twenty-five. Her petition to participate, however, was granted. Vizzana had to wait another six years for the next ceremony.

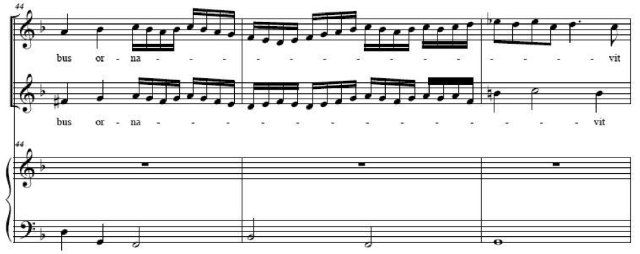

The opening bars of the piece afford an antiphonal impression and one can readily imagine the ethereal sound with which the nuns made their way down the aisle of the church. Vizanna paints a beautiful portrait of a bride adorned for the bridegroom as she places ornate melismas on words such as ‘ornavit’ and ‘coronam’.

Figure 5a: Melisma on ‘ornavit’ in ‘Amo Christum’, bb. 44–46.

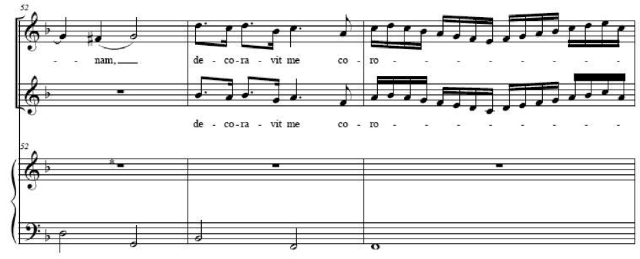

Figure 5b: Melisma on ‘coronam’ in ‘Amo Christum’, bb. 52–54.

Katrina Mitchell

Katrina Mitchell holds a Bachelor of Music in Vocal Music Education and received a Master’s degree in Vocal Pedagogy from Missouri State University. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Musicology at the University of Kansas, where she has served as a graduate teaching assistant and lecturer. She has presented papers at the annual conference of the Great Plains Chapter of The College Music Society, where she served as student representative, and the lecture series, Counterpoint held at Washburn University. She also served as the Great Plains representative on the National Student Advisory Council of the College Music Society. She was the recipient of the Paul Revitt Memorial Student Award for the best student paper presented at the Great Plains Chapter Conference of the College Music Society in March of 2006.

Katrina has also performed vocally with the instrumental collegium at the University of Kansas and with a local early music ensemble, the Spencer Consort. She has completed research in Bologna, Italy for her dissertation ‘Reading Between the Brides: Lucrezia Vizzana’s Componimenti Musicali in Textual and Musical Context’, and presented part of that work at the National Early Music Association’s international conference in York, Great Britain in July. She is currently teaching world music at Metropolitan Community College.

- http://musicasecreta.com/recordings-vizzana.html

- Craig A. Monson, Disembodied Voices: Music and Culture in an Early Modern Italian Convent (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1995), 73.

- H. Colin Slim, ‘Music and Dancing with Mary Magdalen in a Laura Vestalis’, in The Crannied Wall: Women, Religion, and the Arts in Early Modern Europe, ed. Craig Monson (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1992), 139–60.

- The audio examples can be bought from Linn Records <http://www.linnrecords.com/recording-lucrezia-vizzana-componimenti-musicali--1623--cd.aspx>.

- Ibid., 67–8.