Vocal vibrato in Early Music

Richard Bethell

- 1. The reason for this paper

- 2. Vocal vibrato in the Renaissance, Baroque, early Classical and early Romantic periods

- 3. Vibrato singing in the 19th century; a forgotten controversy

- 4. 20th century: what we can learn from Pop and Jazz singers

- 5. Singing Handel: NEMA surveys and Peyee Chen experiments

- 6. Some period voices by 2015, please

- Full text databases: service providers and websites

- Bibliography: books, magazines, newspapers, database sources, recordings

- Biographical note

Video

This page contains audio or video that can no longer be played as it required Adobe Flash. It is no longer playable following the discontinuation of Flash in December 2020.

1. The reason for this paper

This contribution addresses two questions. First, should historically-informed singers use vibrato in early music? Second, given that music is a two-way street, involving both consumers and producers, what evidence is there that audiences like vocal vibrato now, or wanted it in the past?

Why did the National Early Music Association (NEMA) launch this conference, in co-operation with the University of York? This can be answered in one word. Disappointment! Some NEMA Members and early music fans affirm that much early music singing remains historically uninformed and musically unsatisfactory. In particular, the vibrato-infected ‘One Size Fits All’ voice still reigns supreme after 60 years Historically Informed Practice (HIP). By contrast, musical instrument fabrication and performance skills have been transformed over this period. Anthony Rooley gave a good example in his presentation, pointing out that any self respecting professional lute player has to master a variety of instruments, ranging from the renaissance lute to the very different Baroque theorbo, with its unstopped diapason strings. He didn’t develop the point, but the implication was clear. Professional singers with HIP pretensions need a broader skill set in order to interpret properly music from different periods.

Some vocal reform was achieved in the 60s and 70s, with Dame Emma Kirkby and others reviving more authentic styles. Largely thanks to them, good work is being done today by a few individual artists and ensembles, mainly in Medieval and Renaissance repertoire. Unfortunately, the singing of Baroque and Classical music, especially opera, remains unimproved. Why is this? Arguably, one factor was the training of early music directors, nearly all of whom have an instrumental background1 , often with some research involvement. These have contributed significantly to instrumental performance practice, although they may not have possessed sufficient confidence to instruct singers how to go about their business. As a result, we have many excellent period instrumentalists, but hardly any period voices. Michael Morrow, who directed Musica Reservata with John Beckett, certainly tried to wean his singers off vibrato. I performed in the group and sometimes helped Michael by copying parts before rehearsals. We discussed vocal vibrato on several occasions during our late night sessions. He felt that it clashed with the instrumental sound and interfered with intonation, but admitted that he couldn’t win most singers round to his viewpoint. His concerns were reciprocated. I have it on good authority that his vocalists used to complain in the pub after gigs about Michael’s attitude. One grumbled: ‘He wants us to sing like wogs’.

Classical solo singing has changed little since 1950, certainly in the UK. Take Rossini’s operas. His music, often delicate apart from some tub-thumping choruses, requires sweet, beautiful singing, not shouting and screeching. Unfortunately, tenors always project top As, Bs and Cs forcibly from the chest, not in delicate falsetto, as they did in 1820, and some pop singers do now. Massive vibratos oscillate up to a major third from peak to trough. Both faults were expressly condemned by Rossini himself. As a result, Rossini’s operas are never performed, only vandalised. This is, quite simply, not good enough. We must reform. Hence why this conference in general and my talk in particular.

I am not for a moment suggesting that good singing is simply a matter of dispensing with historically uninspired practices. On the contrary, it is about touching the heart, or, hooking up composer’s, singer’s and listener’s emotions on the same wavelength (Judy Tarling’s The Weapons of Rhetoric (2004) discusses the ‘mirror neurons’ idea). For this, the singer needs good taste (I strongly declare that there is such a thing!), rhetorical and creative skills, appropriate technique, and, above all, to feel the music.2 As for delivery, Shakespeare’s Hamlet offers the best guide. Singers should, like actors, ‘use all gently; for in the very torrent, tempest, and... whirlwind of passion, you must acquire and beget a temperance that may give it smoothness’. Pierfrancesco Tosi was of like mind. Noting ‘how great a Master is the Heart’, he urges on singers ‘noble simplicity’ in the aim to ‘preserve music in its chastity’. He praises Giovanni Grossi’s ‘divine mellifluousness’, Luigino’s ‘sweet and amorous style’ and Santa Stella Lotti’s ‘penetrating sweetness of voice’. He affirms that sweetness, softness and tenderness are needed to express the ‘delightful soothing cantabile’: ‘Ask all the Musicians in general, what their Thoughts are of the Pathetick, they all agree in the same Opinion, (a thing that seldom happens) and answer, that the Pathetick is what is most delicious to the Ear, what most sweetly affects the Soul, and is the strongest Basis of Harmony’ (Observations on the Florid Song, Tosi 1720, translated by Foreman 1986, or, translated by Galliard 1747). Judged by Tosi’s standards, today’s classical opera singers are strenuous, loud, obtrusive and overbearing. As Hamlet says, they ‘strut and bellow... tear a passion to tatters, to very rags, to split the ears of the groundlings’.

So much for the rationale. I outline below the structure of this chronologically organised paper:

Section 2 summarises contemporary evidence on vocal vibrato from the Renaissance, Baroque, Early Classical and Early Romantic periods. Musicologists’ conclusions based on this evidence are quoted.

Section 3 covers the 19th century. The main sources are opera and concert reviews from newspapers and journals held on online text databases. So far, I have identified over 4,000 sources, mostly of named singers, on the use or non use of vibrato. The results throw fresh light on the growth of vibrato through the century, which singers introduced vibrato when and on public reactions to the phenomenon.

Section 4 considers briefly pop and jazz singers. The best of these have innate good taste and have rediscovered lost techniques – in an entirely unselfconscious way – providing useful models for early music singing. I analyse a song by Kelly Sweet.

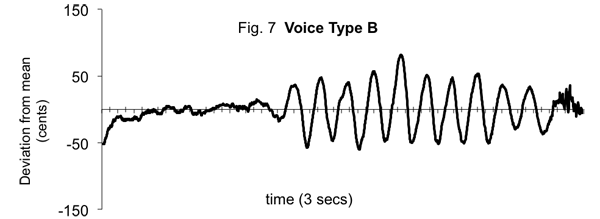

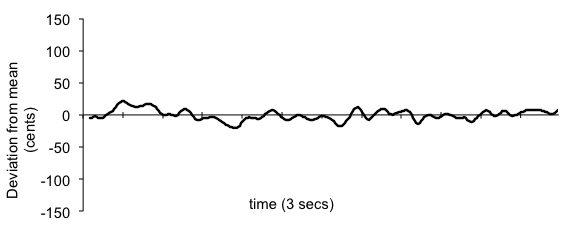

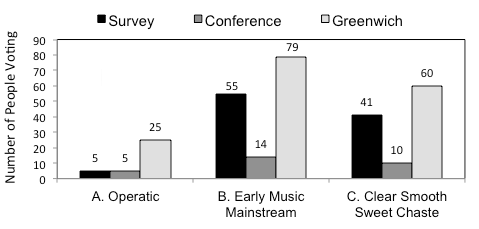

Section 5. This takes us up to the present. The conference prospectus promised an experiment. In fact, we did three. First, I conducted a survey of early music fans for NEMA, which included a question on vocal preferences. Second, recordings were played at the conference of Peyee Chen, University of York post graduate student, singing Handel’s Lascia ch’io pianga in 3 styles. Delegates then voted on their preferences. Third, NEMA carried out a follow-up survey at the Greenwich Early Music Festival. The results of all surveys are included.

Section 6. By way of conclusion, some ideas on where we should go from here are offered. These views and all other opinions expressed in this paper are mine alone, and should not be attributed to other NEMA Council members.

2. Vocal vibrato in the Renaissance, Baroque, early Classical and early Romantic periods

This section is a whistle stop tour of the 16th, 17th, 18th centuries and the first few decades of the 19th century. I refer to some key sources, and musicologists’ conclusions. This evidence suggests that a non-vibrato sound was the norm during the whole period, with very few exceptions.

I have two references for the Renaissance. The first is from Francino Gaffurio’s Practica Musicae of 1496.

[Gaffurio said that singers] should avoid tones having a wide and ringing vibrato, since these tones do not maintain a true pitch and because of the continuous wobble cannot form a balanced concord with other voices. (Gaffurio 1496) (New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 2001)

The next quotes are from Hermann Finck’s Practica Musica of 1556, translated by F.E. Kirby:

The tone should not be too soft or too loud, but rather like a properly built organ, the ensemble should remain unaltered and constant. [Kirby then quotes Finck’s satirical comments on performances he has heard:] Fine compositions were monstrously distorted and deformed, with mouths twisted and wide open, heads thrown back and shaking, and wild vociferations, the singers suffering from the delusion that shouting is the same thing as singing. The bases make a rumbling noise like a hornet trapped in a boot, or else expel their breath like a solar eruption, [thus depriving the composition of its elegance, sweetness and grace. Instead of this, one should employ a quality of voice as sweet, as pleasing, as smooth, as polished as can be produced. Equal attention should be paid to all the parts.] The higher a voice rises, the quieter and more gentle should be the tone; the lower it goes, the richer should be the sound, just as in an organ with various sizes of pipes, both large and small, the larger ones do not overpower the smaller, nor do the smaller ones with their bright tone swamp the larger, with the result that the polyphony and harmony make their way evenly into the ear, in such a way that each voice plainly sounds just as clear, as gentle and as smooth as any other and the listeners enjoy the performance to the full and experience the appropriate emotion. (Kirby 1961) (Finck 1556)

Two conclusions must be drawn from these sources. First, absolute clarity in contrapuntal music is mandatory. Second, vocal vibrato is incompatible both with tonal clarity and with this evidence. But Finck’s essential attributes are not always found today. Vocal balance is often soprano heavy, and the texture infected by vibrato in one or more parts. This ideal renaissance sound was still around in the late 19th century, at least in UK Anglican cathedrals, according to a booklet Advice to singers by A Singer, in Warne’s Useful Books series.

[After discussing the Cathedral Style, and noting that this style] for solo work is detestable [the author goes on to define cathedral singing:] Its chief characteristics are a sort of Passionless ‘statuesqueness’, a steadiness of tone akin to the notes of the organ, which is only fit for accompaniment, an absence of all attempt at personal display on the part of the singer. (Anon 1870).

Gaffurio and Finck would have concurred, but without the underlying slighting tone.

It can’t be denied that vibrato has always been around, at least as an ornament. The existence of the Vox Humana stop is proof of that. Vibrato can be viewed as a kind of ‘Forbidden Fruit’, which was normally disapproved of, but which singers occasionally resorted to. I accept that there may have been some continuous vocal vibrato around 1600, as suggested by Greta Haenen in her conference contribution on Zacconi’s treatise. (Zacconi 1592)

Conference delegates will recall Phillip Thorby’s brilliant workshops. He injected his own asides into the vibrato debate, noting Gerolamo Cardano’s fascination with recorder vibrato. Cardano described how you can use a slightly opened finger hole to produce a vibrato, which was probably similar to the ‘flattement’ technique used in French 18th-century flute playing. He says:

A vox tremula that continues uninterruptedly on individual tones creates an unbelievably sweet effect. [But, elsewhere, discussing the tone to be used in instrumental consort playing, Cardano writes:] Therefore, evenness, accuracy, and smoothness produce a tone that is not only more pleasant but also clear, sustained, and of the proper volume. The opposite characteristics produce a tone that is harsh, uneven, fluctuating, and lacking proper volume. (Cardano Active 1546 to 1576)

So, perhaps selective vibrato is acceptable for solo instrumental playing, but not in concerted performance. While Cardano doesn’t comment specifically on vocal vibrato, his 5th and 6th precepts for singing (quoted below) suggest that he might not have approved of it.

[5] Let him take the greatest care to sing exactly on pitch and not let the note rise or drop a diesis [semitone]; [6] also, let him produce a tone that is clear but not violent, for in this way many singers suffer a ruptured blood vessel or a hernia. (Cardano)

We now move on to the Baroque period. Here are some conclusions of musicologists who have studied the sources:

The evidence leads to the conclusion that any extraneous element in the vocal sound, be it simply vibrato or perhaps other acoustical complexes which the modern ear might describe simply as vocal timbre or ‘grain’, would have been regarded as undesirable. (Wistreich 2000)

Also associated with the new singing was a distinctive use of vibrato. In the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century treatises vibrato is rarely discussed, but by the second half of the nineteenth century the term appears in musical dictionaries and is clearly an issue. As with all aspects of the voice in the pre-gramophone era the subject is problematic because of the difficulty of knowing just what the sources meant. (Potter 1998)

Most writers and singers today agree that vibrato is a natural part of healthy singing. The controversy surrounding its use in Baroque music is usually a question of degree. It is clear from the above quotes [from Zacconi, Praetorius, Bernhard, Bacilly, Roger North and Tosi] that some vibrato was used with cautious moderation, probably more as an ornament than as an ongoing presence. (Elliott 2006)

Several speakers at the York conference discussed the careers and performances of castrati singers. Regrettably, descriptions of castrati sound are rare. Here is the best, by the English translator of Traité des eunuques, by Charles d’Ancillon:

There can be no finer voices in the World, and more delicate, than of some Eunucks, such as Pasqualini, Pauluccio and Jeronimo and were esteemed so when I was in Rome, which was in the Years 1705 and 1706, and I believe are all living at this very Day... yet neither of them had the least semblance with each other... But if Pasqualini was allowed to be the greatest Master, Pauluccio was allowed to have the finest voice. This eunuch who was then about 19 Years of Age (and now about 30) was indeed the Wonder of the World – all the Warblings and Turns of a nightingale, but with only this difference, that it was much finer... [Jeronimo was then described as having] a voice so soft, and ravishingly mellow, that nothing can better represent it than the Flute-stops of some Organs. (d'Ancillon 1718)

Handel was Rome by 1707 and probably heard these artists. This description must surely be our benchmark for any historically informed singing of castrati parts in Baroque operas and oratorios, which are often taken by falsettists. What is required from them in this repertoire is a delicate, soft, ravishingly mellow, nightingale-like, flute stop organ sound. Unfortunately, what we invariably get is from the other end of spectrum - strident, piercing, vibratory and generally loud. Charles Burney would certainly have disapproved of the modern falsettists’ sound, judging from his review of a Dutch synagogue cantor he heard in 1773.

One of these voices was a falset more like the upper part of a bad vox humana stop in an organ, than a natural voice... though the tone of the falset was very disagreeable, and he forced his voice very disagreeably in an outrageous manner.... (Burney, 1775)

Giulia Frasi is one good model for natural, non-castrati sopranos. After noting in his Memoirs that she came to England in 1743, Charles Burney commented on her abilities:

Frasi at this time was young and interesting in her person, had a clear and sweet voice, free from defects, and a smooth and chaste style of singing; which, though cold and unimpassioned, pleased natural ears, and escaped the censure of critics... and her style being plain and simple, with a well-toned voice, a good shake, and perfect intonation, without great taste and refinement, she delighted the ignorant, and never displeased the learned. [Handel hired Burney to give Frasi some elementary training:] Handel used to bring an Air, or Duet, in his pocket, as soon as composed, hot from the brain, in order to give me the time and style, that I might communicate them to my scholar by repetition, for her knowledge of musical characters was very slight. [Burney concludes that Frasi] was the principal singer in Handel’s oratorios during the last ten years of his life. (Klima, Bowers and Grant 1988) (Rees 1819-1820)

Consider briefly what Handel did. Although Frasi was accomplished in some respects (unlike her, very few of today’s sopranos can perform a proper trill), she would be assessed today as little more than a promising amateur, and certainly incapable of being entrusted with major roles in professionally performed oratorio. Why did Handel take such a big risk in employing her? Surely, it was because he wanted her beautifully in tune and coolly expressive sound, which couldn’t have been more different than today’s ‘one size fits all’ mezzo soprano voice.

My last source is Greta Haenen’s Das Vibrato in der Musik des Barock, published in 1988. This 300 page work is widely viewed as the most authoritative guide on the use and non use of vibrato in the Baroque. There are two difficulties with it. First, although the book is known to scholars, most musicians and general readers outside Germany have not heard of it. Fortunately, Fred Gable translated the conclusions chapter of the book, especially for the York conference. This can be downloaded from the proceedings website. I quote below some observations from the translator’s introduction and Greta Haenen’s conclusions.

In my opinion, the use of vocal and instrumental vibrato, both solo and ensemble, is the most controversial and also at the same time the most important aspect of sound production in the whole field of early music. The extent to which vibrato is used and its size and speed can so obscure other elements of a performance that our whole perception of a work can change simply on the basis of vibrato. Thus, this exhaustive study of original sources on vibrato by Greta Moens-Haenen should be greeted with sighs of relief and cheers of congratulations. Finally, the issue of vibrato can be ‘straightened out’. (Gable, Translator's Introduction, Das Vibrato in der Musik des Barock by Greta Haenen 1992, revised 2009)

[In her conclusions, Haenen notes:] Nowhere is a noticeable continuous vibrato approved of. The fact that from time to time warnings are made about it, of course, proves that such a thing existed, but it was at least theoretically not tolerated, and I believe that the better performers tried to avoid it. [Elsewhere, she says:] Other reports of excessive use of vibrato are almost without exception related to a frequent ornamental vibrato, and a mostly constant vibrato is nearly always rejected, if it is mentioned at all. Almost all the sources which argue against a conscious, continuous vibrato come from the second half of the eighteenth century; previously the problem did not exist—with a few exceptions which are directly related directly to singing, all found in Italian sources from around 1600. (Haenen, Summary Chapter from Das Vibrato in der Music des Barock, translated by Frederick K. Gable 1992, revised 2009)

The second difficulty with Haenen’s book is that her findings have been ignored by vocalists in the 22 years since publication. Fred Gable’s hope that vocal vibrato in Baroque music can be ‘straightened out’ remains unfulfilled. If anything, the timbre of today’s vibrato singers (subsequently referred to in this paper as vibratoists) remains as corkscrewed as ever. Why is this? In the first place, the adoption of Haenen’s findings has, so far, been thought far too radical a step for to-day’s singers to entertain, given that they have been trained in a completely different style. Some vocal students I talked to at the University of York pointed out that, if they sang authentically, they might upset audience expectations and get type cast as ‘white voiced’ specialists, afflicted with the ‘cathedral hoot’. Their reluctance is understandable, if regrettable. Also, the widespread opinion remains: ‘Surely there must have been at least some vibrato, at all times!’. James Stark (Stark 1999), Frederick Neumann (Neumann 1989) and Robert Donington all believed this to be the case, and it was my impression that their views are still shared by a number of speakers and delegates at the University of York Conference. Donington thought that the recorded work of singers like Melba and Patti embodied the true bel canto style which originated in the 18th century, or even earlier. He said in Music and its Instruments:

It should perhaps be added that with the voice, as with the strings, vibrato is a natural and historical, not an artificial or recent resource. – Vibrato should not always be present, particularly in early music, but requires excellent technique and very great discretion. At no period, however, does the pure and uncoloured voice, without vibrato, and sometimes called voce bianca, white voice, appear to have been recommended or tolerated except for rare and special effect. (Donington 1982)

Fred Gable has effectively rebutted the pro-vibrato views of Donington and Neumann in an article in Performance Practice Review (Gable, Some Observations Concerning Baroque and Modern Vibrato 1992).3 I contribute in Section 3 below additional evidence from the 19th century confirming that they were wrong. But, before moving onto my recent research, we will look briefly at the Early Classical and Early Romantic Periods.

In his Heart to Heart, Expressive Singing in England 1780-1830, Robert Toft concludes:

The basic sound of the voice appears to have contained little or no vibrato. Singers were expected to be able to sing without any hint of trembling or wavering, and those who could not were subjected to ridicule in the musical press. (Toft 2000)

Bruce Haynes in The End of Early Music comments:

Period style is not totally at odds with Romantic style. Some eighteenth-century practices4 were carried over until somewhere around 1850, and a few even longer. (Haynes 2007)

Clive Brown observes in Classical and Romantic Performing Practice 1750-1900:

The modern concept of continuous vibrato as a fundamental element of tone production began to evolve, under Franco-Belgian influence, only towards the end of the nineteenth century, but it was not until the early decades of the twentieth century that this new aesthetic began to be firmly established and widely accepted. (Brown 2004)

This is also the place to mention that my tremolo searches of 17th- and 18th-century newspaper and magazine sources generated only a single hit, viz. Robert Bremner’s essay Some Thoughts on the Performance of Concert Music, published in Edinburgh Amusement and (in a slightly abridged form) in The Westminster Magazine (Bremner 1777).5

Pierfrancesco Tosi’s warnings that singers must avoid trembling or become ‘subject to a Flutt’ring in the Manner of all those that sing in a very bad Taste’ (Tosi, Observations on the Florid Song or, Sentiments on the Ancient and Modern Singers, transl. by Galliard 1747) were sometimes plagiarised by other writers later in the century. Certainly, these indicate that some vibrato singing occurred. Commentators have argued that Tosi’s ‘bad taste’ observation was just his opinion and that others in Tosi’s time might have deemed it good taste. But the extreme rarity of any 18th-century reviews or descriptions on vocal tremolo or tremulousness in the UK could indicate that, if such vibratoists existed, they seldom trod the boards of Drury Lane Theatre or anywhere else in a professional capacity. I suggest that 18th-century vocal vibrato in the UK was the work either of amateurs or of ageing / retired professionals.

Finally, Burney reported two cases where vocal vibrato could not have been used.

[The singing of Cecilia Davies, a prima donna soprano, was a hit at the Austrian imperial court. Her duet singing was described in a letter from Metastasio:] when accompanied by her sister [Mary] on the Armonica, she has the power of uniting her voice with the instrument, and of imitating its tones, so exactly, that it is sometimes impossible to distinguish one from the other. (Burney, 1772)

[When soprano Franziska Lebrun sang with her husband Ludwig’s oboe (c.1879–81), she] copied the tone of his [her husband’s] instrument so exactly, that when he accompanied her in divisions of thirds and sixths, it was impossible to discover who was uppermost. (Burney, A General History of Music 1789)

To sum up, there is overwhelming evidence that continuous vocal vibrato was very rare in the Renaissance, Baroque (except c.1600), early Classical or early Romantic periods. We know from recordings c.1900 that vibrato singing was almost universal, albeit somewhat narrower than today’s accepted norm. So when did the change take place? If Robert Toft and Clive Brown are right, this must have occurred some time between 1830 and 1900. I think I have some answers to this question and will continue the story in the next section.

3. Vibrato singing in the 19th century; a forgotten controversy

The main issue addressed here is: When did vibrato come in during the century? Or, was it actually there all the time, as Robert Donington asserted?

Before starting work on the topic, I mentioned to Conference Chairman John Potter that, before tackling the vast library of 19th-century treatises and biographical material, I would pluck some ‘low hanging fruit’ from the full text databases. What I encountered was a fruit forest. So far, after computer searches though thousands of acres of newsprint, over 4,000 notices and other references to vibrato and its synonyms have come to light, mostly featuring named singers.

This contribution to the conference proceedings is my progress report. I hope to publish a fuller account in due course. I’ll come clean now on a couple of limitations. The first relates to the scope of the exercise, which is limited to English language sources. Clearly, Italian, French and German sources are equally important. However, many of my sources include performances by the best singers from mainland Europe working in the UK and the US, which could afford the highest fees. Second, by definition, surveys of this sort can’t be comprehensive. Some important sources have not yet been scanned. It couldn’t have been done properly 5 years ago and it will need to be updated in a few years time. If you take the important British Periodicals Collection I and II (this can be accessed in major national libraries), some sources only appear to have been acquired in the last year or two.

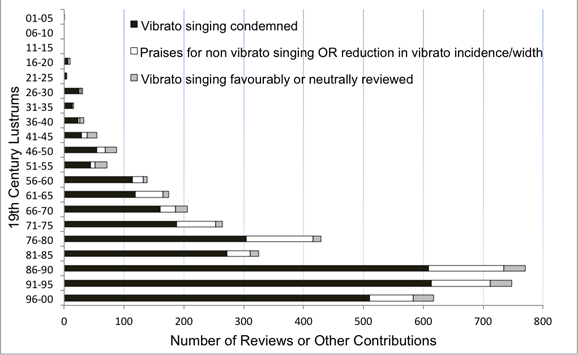

Fig. 1: Views of 19th-century reviewers (English language)

But full text databases have huge advantages as research sources. First, their immediacy. Opera and concert reviews describe how music was actually sung – live – earlier this evening or last night. They are not normally concerned with vocal theory or with how teachers or authors thought it should be sung. Another problem with tutors or methods, generally written by retired singers or musicians, is that they do not necessarily reflect actual performance practice. If they do, they could promote outdated styles from 20 years earlier when the author was singing professionally. Second, the quality (and quantity) of the reviews was high. Only highly qualified writers, generally accomplished amateur musicians themselves, were appointed as critics by national newspapers or reputable magazines. Some are still respected authorities today, including Henry Chorley (UK), Eduard Hanslick (Vienna) and W. J. Henderson (USA).6 As opera and concert going was one of the main leisure pursuits of their educated middle class readership, editors were happy to allocate lots of space to critics’ notices. Generally, concert and opera singing attracted most of the coverage, as critics had little new to say about the music, given that the repertoire consisted mainly of enduring favourites like La Traviata.

Now for the big question: when did vibrato start to emerge? A top down view of the results is shown at Fig. 1 above. This shows the number of sources identified in each 5 year period, broken down into 3 categories. Note the preponderance of uncomplimentary notices (black bars), which account for 75% of the 19th-century total. 18% of the sources (white bars) praise non or reduced vibrato singing. Only 7% (grey) report on vibrato in favourable or neutral terms.

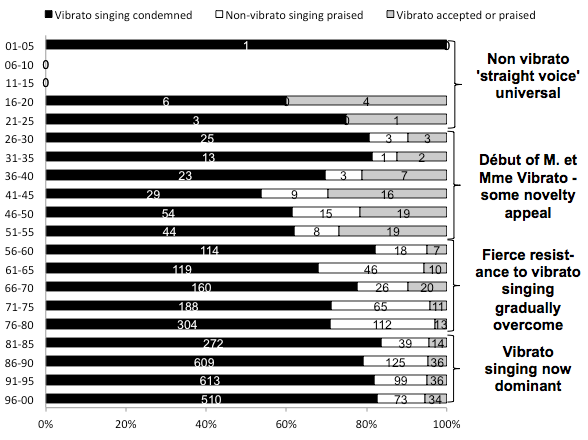

It’s instructive to look at the numbers in percentage terms, over four different periods (see Fig. 2). I have presented my analysis and examples in four separate sections, corresponding to this classification. However, the division into periods should not be interpreted as hard and fast, given that the growth of vibrato was a gradual phenomenon from 1825 or so onwards.

Fig. 2: Stages of vibrato introduction (mainly UK, N. America, Australasia)

Universal straight voice (1800 to 1825)

As you can see from Fig. 2, only a single, slightly critical, vibrato notice (quoted in the next paragraph) appeared in the first 15 years of the century. In the next 10 years to 1825, only one report was picked up each year, on average. Clearly, any vibrato singing which occurred just wasn’t registering with the musical public as a performance practice trend.

There were occasional reports of initial nervousness causing tremulousness in the first few decades of the century. For example, a notice on Mrs Elizabeth Billington in The Times says:

Some of her lower notes were rather tremulous at the commencement of the Opera; but this circumstance must be attributed to her emotions on again coming forward as a candidate for public favour after so long an interval. (Reviewer, Times, Mrs Billington as Mandane in Ataxerxes, at Covent Garden 1801)

But this is not proof of intentional or habitual use.

Apart from a few references to Paganini’s left hand vibrato, used as a comic turn, one of the earliest references to vibrato was included in a review of John Braham, although it is clear that his ‘tremulous fervour’ only occurs as an occasional, expressive effect:

But the Italian refinement seems to puzzle him; and the feeling and tremulous fervour which occasionally delight us in his voice, are apt to be followed by such a heap of common-place quavers and ornaments, such a scatter of base coin to create a scramble among the galleries, as becomes the more offensive from the true wealth that precedes it. (Reviewer, Examiner, Reason for omitting John Braham from the singers who "shine at Oratorios" 1820)

Braham’s re-appearance much later, at the age of 70, was reported thus:

His organ has none of the tremulousness of RUBINI, nor is its declamatory power impaired. (Reviewer, British Minstrel, Braham's Re-appearance at St. James' Theatre 1844)

The sources suggest that Miss Anna Maria Tree was the first professional vibratoist working in the UK. She arrived on the London scene in 1819, and had a short professional career of about 5 years, before retiring on marriage (New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 2001). The London Magazine of July 7th 1820 reported:

Miss Tree thrills through florid notation, like the soaring lark, which has just now, by its song of extacy [sic], while trembling, circling, poising herself in her ascent, courted the regard of the writer, —filled him with some of her own delights, and furnished him with a similitude. (Reviewer, London Magazine, Review of Anna Maria Tree 1820)

I was inclined to disregard the foregoing as poetic fancy. But two other notices suggest that trembling probably means tremulous:

The more we see of this lady [Mademoiselle Bonini], the more we like her... This effect, moreover, is greatly heightened by the fascinating quality (timbre) of her voice, in which there are some beautiful notes of the sweetest tremulousness that vibrate to the heart of the hearer. It was a similar quality of tone which proved irresistibly sweet in Miss Tree’s voice, and rendered her singing more effective than that of a rival of greater professional skill. (Reviewer, New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal, Bonini as Agia in Pictro l'Eremita (version of Moses) 1826)

[Miss Tree’s voice] is not at all powerful; but it is perfectly clear and sweet in the upper notes, and some of the lower ones have a fine, rich glowing tone—like the musical murmur of the honey-bee. (Reviewer, Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Miss Tree and Mr Phillips 1819)

The last reference suggests a fast narrow amplitude vibrato, occurring frequently but not necessarily continuously in her lower notes.

Innovating vibratoists (1825 to 1855)

Histories invariably name tenor Rubini as the singer who invented vibrato, in about 1834. He was followed his pupil Pantaleoni (1836), the bass Fornasari (1844) and the tenor Tamberlik (1850). But, it seems that wiggle-voiced7 ladies were there first, by a decade or so! Tree (1819) was followed by female vibratoists Bonini in 1826, Feron (1827), Schutz and Meric-Lalande (both in 1830). Awareness of vibrato singing grew steadily amongst the musical public. The proportion of favourable or neutral reviews was relatively high, at 20% to 25%. The sheer novelty of vibrato timbre had some appeal, which was occasionally recognised at the time. It was obviously quite new to the music critic of The Caledonian Mercury, besides others in the audience. He commented as follows:

The long shake and undulation of the voice at the end of the line, ‘We hail her with three cheers’, is quite a new feature, and produced a startling effect. (Reviewer, Caledonian Mercury, Review of Mr. Templeton in the musical farce, The Waterman 1938)

But the singers involved were too few in number to be a threat to the established order.

Here are two further examples of innovating vibratoists. First, a scathing account of the contribution by Meric-Lalande to Bellini’s Il Pirata. It is taken from a letter by Maria Malibran, daughter of Manuel Garcia, a famous but rather jealous rival. It was probably performed in May 1830. Maria was a drama queen herself and she brings the scene to life.

I went to the opera with Lady Flint, her husband, and her daughter; and having taken my seat and adjusted my lorgnette, I impatiently awaited the entrance of the Pirato, who was represented by Donzelli. The overture commenced. Humph! very so so. It is not effective. The curtain rose. The opening scene was pretty, and was loudly applauded. Dramatic authors and composers know how much they owe to the scene-painter. Enter Il Pirato. He blustered, and strutted about, sang loudly, enchanted the audience, and was clapped. In acknowledgement of the applause, Donzelli bowed at least thirty times, and continued bowing until he was actually behind the side-scenes. The first air was tolerable. Change of scene. Venga la belle Itáliana, said I to my little self. I was all impatience, and as she appeared I stretched over the box to catch a glimpse of her. Alas! what a disappointment! Picture to yourself a woman of about forty, with light hair and a vulgar broad face, with an unfavourable expression, a bad figure, as clumsy a foot as my own, and most unbecomingly dressed. The recitative commenced. Her voice trembled so, that none could find out whether it was sweet or harsh. I therefore waited patiently for the cavatina. It commenced, and the prima donna opened her mouth with a long tremulous note. Concluding that this arose from timidity, I could not help pitying her. But alas! the undulating tones of her voice continued throughout, and utterly spoiled the pretty cavatina. At its conclusion she was vociferously applauded, and made a thousand curtsies, which is the custom in London. Next came the beautiful duet. In this she was just as cold and tremulous as before. In a word, not to weary you with a long account of each morçeau, she finished her part in the same bad style in which she began it. [She concludes:] I have discovered that this tremulous style is Madame Lalande’s constant habit of singing. It is her fashion—immovable, fixed, eternal! You may therefore guess how well our voices are likely to blend together—two and two, like three goats. Her middle notes are wiry, and have a harsh and shrill effect. (Reviewer, Monthly Review, Memoirs of Madame Malibran, by the Countess de Merlin and Other Intimate Friends 1840)

I include excerpts from two reviews on one of the most famous early vibratoists, Enrico Tamberlik. Critics approved of his performances on the whole.

But Tamberlik—the glorious Tamberlik!.... I don’t like the constant tremulousness of his voice; it is a defect in him as in Rubini; but what singers they are in spite of their defects! Tamberlik is not perfection—he is not equal to Mario—but, all deductions made, he is the second tenor in Europe, and one who really does transport his audience. (Reviewer, Leader, The Arts, Masaniello 1851)

[The Times] The romance in the first scene, ‘Quando il cor’, at once showed that Signor Tamberlik’s voice was in excellent condition, while the richness of his tones, accompanied by that peculiar ‘vibrato’, which, after some discussion, has been accepted not merely as a peculiarity, but (when under entire control, as now) a beauty, gave additional effect to his large and finished style of phrasing, leaving the ear and judgment equally satisfied. (Reviewer, Times, Royal Italian Opera, Donizetti's Maria di Rohan 1852)

Fierce resistance to vibrato singing gradually overcome (1855 to 1880)

In this phase the innovators were followed by numerous imitators. Around the mid-1850s, reviewers reported that continuous vibrato was becoming common, as per examples below. The proportion of favourable or neutral reviews on vibrato fell to about 5%. From 1860, critical notices on vibratoists come thick and fast, and there’s no space to list all the singers in this paper.

Madame Doria made much too frequent use of the tremolo, which appears at present to be so fearfully in fashion. (Reviewer, Manchester Guardian, Review of duet from Spohr's Jessonda 1853)

For some time past it has been my fate to hear no sopranos but those third rate singers, who endeavour to conceal their incapacity to utter a full, clear tone, by a constant tremolo, like a whistle with a pea in it. This as an ornament, or rather as expressive of deep emotion, is at times very effective; constantly heard however it becomes unbearable. (Dwight’s Journal of Music, Thayer 1854)

[The critic condemns Maria Spezia-Aldighieri for her perpetual vibrato, referring to it as] that besetting sin of a large proportion of singers of every clime. (Reviewer, Musical Gazette, Review of Maria Spezia-Aldighieri as Leonora in La Favorita 1957)

We... express the hope that this distinguished singer (Constance Didiée), will not fall into the error, becoming too common now, as a genre, of indulging in the tremolo. (Reviewer, Evening Star, Review of Constance Didiée in Donizetti's Maria di Rohan (London) 1957)

[After taking to task Angiolina Bosio, Maria Spezia-Aldighieri and Angiolina Ortolani for their vibrato, the critic concludes:] putting a ‘tremulant’ on the voice would appear to be quite a fashion. (Reviewer, Musical Gazette, Review of Angelina Bosio in La Traviata 1857)

The voice of Madlle. Titiens is of full and telling quality, of unimpaired freshness, and free from any unpleasant peculiarity, and above all from the tremulousness, involuntary or affected, so common among singers of the day. (Reviewer, Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science, Notice on Thérèse Tietjens in Les Huguenots 1858)

As we move into the second-half of the century, the critics became increasingly hostile to vibrato. They heartily detested it with a bitter loathing. Reviewers frequently couple tremolo or vibrato with derogatory adjectives such as aggressive, detestable, hideous, horrible, vicious, abominable, evil, odious, etc. Nor is this hostility confined to the critics, who were clearly echoing their readers’ views, besides expressing their own. Composers, singing teachers, competition adjudicators and singers themselves all joined the chorus of opposition, as did knowledgeable opera fans, from Grand Old Man William Gladstone downwards.

Vibrato singing dominant (1880 to 1900)

It is clear from the sources that most opera performers, if not concert singers, were using some vibrato during this period. There were fewer notices on non vibrato singing, as is apparent from the chart at Fig.2 above. While actual statistics are hard to come by, the following claim by the famous tenor Sims Reeves carries some weight:

According to Mr Sims Reeves, writing in ‘The Idler’, it is scarcely necessary to describe the tremolo. He might have added that, if one is to be polite, it is also impossible to describe it. The veteran tenor goes on to point out that five out of every six modern singers are afflicted with this wobble, ‘and consequently there is a great deal of make-believe that the tremolo is a splendid vehicle for the expression of sentiment and passion. But experience soon proves that an audience never mistakes affectation—and tremolo is nothing else in effect—for sincerity; and the singer finds, when it is too late, that the tremolo has literally got him by the throat and he cannot get rid of it....’ (Reviewer, Weekly Standard and Express: Our Musical Column, by ‘Musicus’, on Mr Sims Reeves 1900)

But, somewhat surprisingly, there are a number of reports from this time claiming that the vibratoists were on the retreat, in both the UK and the US.

The characteristic feature of the Italian style is the tremolo, and that is no longer popular. Instead of it, the round, full, clear tone is demanded. (Reviewer, Boston Daily Globe, How to Sing Without Hurting the Mucous Membrane of the Throat 1886)

[Following a notice on a Signor Lorrain who was ‘not altogether free from the tremolo’, the reviewer concludes:] The day is possibly not far distant when the vexed question of the tremolo must be settled one way or the other. It is no longer held to be mere evidence of fatigue, and it is now generally admitted that this most vicious of all vocal mannerisms is actually cultivated as a grace in some of the Continental singing schools. Thirty years ago or more a similar craze was in full force, particularly in Italy, but English audiences have always refused to tolerate it, and, with one or two notable exceptions, the great vocalists of our own time have all escaped the taint. (Reviewer, Daily News, Review of Faust 1887)

She ... has either been ill-advised or unadvised, or she would not impair her natural gifts by such a profuse use of the vibrato, which happily seems to be dying out; not, however, before it has buried the reputation of some who would otherwise have been fine singers. (Reviewer, Sheffield & Rotherham Independent, Miss Effie Thomas in St John the Baptist 1888)

This style of singing came into vogue about 40 years ago, but, happily, it is now beginning to disappear. (Reviewer, Musical Herald, Questions and Answers, Vibrato and Tremolo 1892)

[It, continuous tremolo,] has gone out of fashion in the cultivated musical world for a long time, and those singers who imagine they are up-to-date in continuing it, really show that they are among the has-beens. (Reviewer, Deseret Evening News, The "Gargling" Style 1906)

There could be an element of wishful thinking here. But, a counter-reformation of sorts was certainly taking place. There are reports of singers being sacked for their vibrato, or even run out of town. Critical hostility certainly intensified towards the end of the century. The sources are sprinkled with anti-vibrato diatribes, anti-tremolo jokes, reports of vocal sketches caricaturing vibrato singing, satirical poems and letters to the editor from Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells. Editors even allowed vibratoists to be mocked by gratuitous ad hominem jibes. For example, two critics or correspondents for the New York Times were unsparing of the unfortunate Émil Cossira:

The tenor was M. Cossira, a gentleman who disported himself as a Romeo of 200 pounds avoirdupois and possessed a small tremulant voice like the patter of rain on a tin roof. In the expressive language of the American boys, he made me tired. The rest of the singers are absolutely not worth mentioning. They would be considered bad in comic opera in New-York. They all possessed small wooden voices and displayed the French vibrato in all its iniquity. I never heard worse singing, not even in the American Opera Company (Reviewer, New York Times, Roméo et Juliette, Paris Grand Opéra 1889)

There is, or has been, trouble in the French opera company at New-Orleans, owing to a disagreement between Mme. Martini, soprano, and Mme. Cossira, wife of the tenor. Cossira received some flowers intended for Mme. Martini. She delicately called his attention to the fact, and he delivered them to their rightful owner, with a courteous apology for his mistake. But the incident annoyed Mme. Cossira. So one night when the tenor was handed some flowers intended for Mme. Martini, Mme. Cossira carried them to the soprano, and, saying ‘You took the others, now take these!’ threw them at her. Such are the gentle amenities of life among the song birds. It may be mentioned that Mr. Cossira is a large, fat tenor with a small, lean voice. The little voice and the large body wobble in unison with an obese French tremolo when the tenor is at work. The writer had the misfortune to see and hear this gelatinous shaker in Gounod’s ‘Romeo et Juliette’ at the Paris Grand Opera. Physically he was the greatest Romeo we ever saw. Otherwise he wasn’t. (Reviewer, New York Times, Trouble in the French opera company at New-Orleans 1890)

Attacks on both vibrato and tremolo continued. It sometimes seems as if, once it was clear that vibrato singing was well entrenched, protests against it became even more vehement. Nor were these limited to opera and concert singing. A heartfelt rant by an Eisteddfod adjudicator, Dr. Varley Roberts, was widely reported in the provincial press. Interestingly, his proportion of ‘defiled’ vibratoists is close to Sims Reeves’s estimate quoted earlier.

Were I a Welshman I might wax enthusiastic about the National Eisteddfod held last week. As there is no Taffy blood in my veins I will content myself by commending to the careful perusal of all vocalists—teachers and students alike—who read these lines a few sentences uttered by one of the adjudicators, Dr. Varley Roberts, perhaps best known as the composer of the anthem ‘Seek ye the Lord’. As a friend to Wales, he said he must again assert that the great failing in his opinion, in the Welsh singing was the abominable tremolo. If their singing was to be worthy of the voices that Wales possessed, this defect must be utterly and entirely obliterated. In nearly all the candidates that had presented themselves this eternal tremolo was to be found—certainly twenty-two out of the twenty-seven in one particular solo competition were defiled—he could use no other term—by this abominable tremolo. It needed some one to speak out, and he did not care what the press said, what Wales said, or what all the musical critics in the country said. It was the curse of the principality, and it must be stamped out. If he himself were able to do something towards that end, he would have done a great work for Wales. Not only Wales, but Sheffield may take these words to heart. (Reviewer, Sheffield & Rotherham Independent, Music & The Drama, Dr. Varley Roberts on Vibrato 1900)

What were are the arguments of the pro-vibrato school? I searched for notices and articles defending vibrato singing, but these were not forthcoming until around 1870. Indeed, contemporary reviewers sometimes noted the complete absence of any sort of counsel for the defence. However, I did find a comment from the Graphic on the tenor Nicolini, Patti’s husband, who was often criticised for his vibrato, as follows:

Signor Nicolini has rare advantages, both of person and talent. His appearance and bearing are more than commonly agreeable, and he is not without admirable qualities, both as actor and singer. True, the modern French vibrato is a drawback to English ears; but we are getting accustomed to it, and the fault is less noticed than ever before. (Reviewer, Graphic, Review of Nicolini 1872)

This is not so much a defence of vibrato, as a reluctant concession to actual events.

The evolving views of Francesco Lamperti, an important Milan based vocal coach, are significant. In his treatise, translated by J. C. Griffith and published in 1877, Lamperti says:

In conclusion, I would put the pupil on his guard once more against the trembling of the voice, a defect which in the beginning of this century was sufficient to exclude any singer from the stage. I would not have him however confound this with the oscillation produced by the expression of an impassioned sentiment. (Lamperti, A Treatise on the Art of Singing 1877)

However, in the updated 1884 edition of Lamperti’s book, translated by Walter Jekyll, the last sentence has been changed to:

I should remark that tremulousness must not be confounded with oscillation, which is a good effect produced by a strong, vibrating, sonorous voice. (Lamperti, The Art of Singing according to ancient tradition and personal experience. 1884)

This is a major change of emphasis. In effect Lamperti is moving away from Garcia’s directive, that vibrato may only be deployed selectively to express powerful emotions, and implying instead that it should be used continuously. This conclusion is backed up by a Question and Answer type article, in which the anonymous writer says:

In Italy my master was Lamperti, who deservedly has the reputation of being the greatest teacher in Europe. Among his pupils who have gained fame are Albani and Campanini. Lamperti teaches the old Italian system.... When I was in Milan over 300 Americans were there studying music. [In reply to the following question] What have you to say of the tremolo so often noticed in singers? [the writer says] That comes from the explosive use of the breath. It is a defect, but the vibrato, often confounded with the tremolo, is a natural effect. The natural mode of breathing is the only one by which the larynx is left wholly unconstrained—the sine qua non of the good singer. (Reviewer, Boston Daily Globe, About the Old Italian System of Tone Production-Many Hints to Singers and Teachers 1886)

There is little question that tremolo and vibrato levels were becoming more noticeable, that is, oscillating more widely, as the end of the century drew near. A Times reviewer commented on a performance by Victor Maurel in Rigoletto:

Some years ago the French baritone was considered to be one of the worst victims of the vibrato on the stage; this is so no longer, not on account of any remarkable improvement in his method, but for the reason that the epidemic has worked such fearful ravages of late years as to make him appear, by comparison, to sing almost steadily. (Reviewer, Times, Victor Maurel in Rigoletto at the Royal Italian Opera 1890)

Now is the time to discuss definitions. First, we look at this question: When reviewers discuss tremolo or vibrato singing, do they mean variations in intensity or pitch? While pitch oscillations are much more common, there are a few references to apparent intensity vibratos. For example:

Signor Gayarré, the chief tenor, has neither sympathetic tone in his voice nor artistic warmth in his style, and when, added to this it is said that, by his use of the vibrato, his delivery degenerates into a piteous bleat, almost as sad as that uttered by M. Capoul (another of the tenors), but of a more vigorous character, it will be gathered that there is not much to be gained by listening to such vocalists. (Reviewer, Monthly Musical Record, General review of Opera at Covent Garden 1878)

Definitions were changing rapidly. In the first half of the century, any sort of vocal unsteadiness, whether oscillation or bleating, was nearly always described as ‘tremulousness’. It was followed shortly after by ‘tremolo’ and then ‘vibrato’. All three terms are synonymous through most of the century. But in the last two decades, commentators start to discriminate between oscillation levels. If narrow, it was called vibrato and the singer was sometimes praised. If wider, it was dubbed tremolo and the singer censured. Worst of all, very wide oscillation was described as wobbling8 (UK), or wabbling (US), and condemned as unacceptable.

The distinction between acceptable and unacceptable degrees of oscillation was made clear in the following notice, published in Longman’s Magazine.9 It ‘hit the spot’ and was widely published elsewhere. The author somewhat reluctantly accepts vibrato, because it is a fait accompli and it (supposedly) allows the singer to obtain much greater power. But, he reaffirms his disapproval of the more extreme tremolo.

Many singers, especially young singers, fall into the habit of using the ‘tremolo’ or ‘vibrato’. The former is, as the word implies, a trembling of the voice, and may be dismissed as simply vulgar and offensive. The ‘vibrato’ stands on a different footing. It is impossible to pass a sweeping condemnation upon it, seeing that it is adopted by nearly the whole Italian school— that school to which we are accustomed to look for the proper production of the voice. (Murray’s Magazine, Ingleby 1888)

There are many review comments from the last decade of the 19th century implying that some vibrato was just about acceptable or even desirable, certainly in opera if not in concert singing. Here are some typical review extracts:

Signor Rawner is a robust tenor of the school now popular in Italy. He has a powerful voice, which he uses unsparingly; and although not free from the vibrato, the defect is not so pronounced as to become unpleasant. (Reviewer, Daily News, Il Trovatore at Covent Garden 1890)

... his voice might have been steadier with an advantage; an amount of tremolo which is scarcely noticed on the stage at the present day is most obtrusive in the concert-room. (Reviewer, Times, Mr William Ludwig at Crystal Palace Concert 1891)

... the vibrato is used effectively and not indiscriminately. (Reviewer, Boston Daily Globe, Mme. Eames' Recital, Fashionable and Critical Audience Enjoy the Concert, Chickering Hall 1893)

[Denis] O’Sullivan was an ideal Shamus O’Brien... In Concert he is afflicted with a vibrato that borders on a tremolo, but in opera this defect is scarcely apparent, and otherwise his singing leaves nothing to be desired. (Reviewer, San Francisco Call, Shamus O'Brian at the Tivoli 1897)

...he needs to guard against his tendency to indulge in the tremolo, to the extent of almost wabbling on some of his notes. (Reviewer, San Francisco Call, William Keith's Fine Singing, Concert at Columbia Theatre 1896)

Mr. Hedmondt’s Tannhaüser was a most powerful and impressive performance. ... in place of the sentimental lyrical lilt which seems to be the ideal of so many he brought out a voice vibrating in every note with strenuous masculine passion. This is just what is wanted for a Tannhaüser. We heard his slight tremolo criticised, but it cannot be said that it spoilt or even noticeably detracted from his performance. (Reviewer, Sheffield & Rotherham Independent, Tannhaüser at the Theatre Royal, Moody-Manners Opera Company 1900)

The best magazine around today for early music concert and CD reviews is the Early Music Review. EMR reviewers evidently enjoy vibrato in moderation. But, if it is excessive, the singers concerned are often censured10 using similar language to their counterparts in the 1890s. The point I’m making is that today’s reviewers, in setting standards for historically informed singing, are only prepared to take the clock back 120 years to 1890, but not an additional 60 years to 1830. So far, that is.

But, returning to the 19th century, the general disapproval of any kind of unsteadiness in singing continued towards the end of the century and beyond. Here are extracts from a diatribe in the Magazine of Music, of 1890, headed ‘Vocalists and Wobblers’, which was reprinted by other newspapers and magazines in the US and the UK. This contains interesting historical perspective, which is consistent with my sources and gives a good impression of the ding-dong battle which was going on. The reference to Truth in the first line is not to its meaning as a good but to the title of a magazine, unfortunately not yet acquired in full text form:

We are glad to see a certain class of singers fitted by (and with) Truth with the title of ‘Wobblers’; and we hope that the nickname will stick, and that a wholesome dose of derision may prove a more effectual remedy than argument. Truth considers that operatic singers cannot succeed in England if affected with this vocal vice, and we are unfeignedly glad to hear it... Fifty years ago a singer would have been hissed as incompetent whose voice quavered in this preposterous fashion. / The chief difficulty now presented to any impresario is to discover a competent operatic vocalist free from the tremolo. The story is an old one, and it continually repeats itself. Rubini possessed this, the ugliest of vocal vices, and, in his day, he set the fashion to a crowd of imitators, who were finally all snuffed out by Mario. The disease broke out again on the Continent about thirty-five years since, but it was stopped here by the success of Clara Novello, Giuglini, Jenny Lind, and Titiens, all of whom were free from it. The defect slumbered among the dii minores of the Continent for a lengthened period, until the success achieved by Gayarré once more made the acquisition of the tremolo a glorious achievement. (Reviewer, Magazine of Music, Vocalists and Wobblers 1890)

The author goes on to mention other singers supposedly free from the tremolo. There is a problem with this list, which I will come to shortly. As we’ve seen, reviewers quite often distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable degrees of vocal wavering. However, for some, ‘vibrato’ remained just as much a term of abuse as ‘tremolo’. Singers in particular found euphemisms to replace the word. Take the soprano Emma Calvé. She had a fairly assertive vibrato around 1907, albeit narrower than those common today, as we can clearly hear from a recording made at that time (Calvé, The Era of Adelina Patti, Disc 1, Prima Voce Nimbus Records, Carmen, Habenera 1907). But she avoided the word, as we can see from her article You can Learn to Sing at home:

Avoid the tremolo as you would the plague. Some very young singers do not understand the difference between the tremolo, which is all that is meretricious and destructive, and the thrill [emphasis added] which is beautiful and belongs to our art. (The Times, of Richmond, Virginia, Calvé, You Can Learn to Sing at Home 1900)

Certainly by 1905, perhaps earlier, another new term defining the permissible level of wavering was introduced: resonance. It’s still in use, although mainly as a technical term used by singers and vocal coaches. Here are two quotes using this new word.

The coming of Melba, it is to be hoped, will have a lasting impression upon the musical circles of Cedar Rapids. The young vocalists who heard her last night can now appreciate the difference between resonance and that ‘tremolo stop’ effect that so many are acquiring, to the irreparable injury of their voices and the disappointment of their friends. (Reviewer, Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, Cedar Rapids gets first Real Musical Treat 1905)

Referring to the notice of a vocal recital your always interesting and careful critic will forgive my pointing out that he for once sinned in making ‘tremolo’ and ‘vibrato’ synonyms. The best Italian and French schools of singing thoroughly and emphatically deprecate the ‘tremolo’ as a proof of diaphragm instability, or other fault of vocal production, and hold the ‘vibrato’ to be the true ringing resonance of the well-trained voice, heard in every good singer from Melba and Caruso downwards. (Daily Mail, Moncrief 1906)

The second part of the last sentence in the Daily Mail quote was by now the received wisdom, and it remains so today.

Non-vibrato singing in the 19th century

Fig. 2 shows there were 600 reviews praising non-vibrato singing in the second-half of the 19th century. Of course, just because a critic reports that Mario has no vibrato, that in itself does not constitute incontestable proof that he sang with a totally straight voice. However, some reports suggest that straight, non-vibrato singing was a reality, even later in the century.

William Gardiner, in The Music of Nature, 1832, comments:

Madame Ronzi de Begnis appeared in the year 1821. With an arch and beautiful face, and slender voice, she executed everything with all the neatness and ready precision of the oboe. This instrument she could imitate exactly, by rather closing her mouth... (in) duettos written purposely for her and her husband, by Rossini. (Gardner 1832)

Clara Novello was a famous concert and oratorio singer. Born in 1818, she was active on and off from 1833 to 1860. The following notices leave little doubt that she sang in straight voice.

At the early age of eleven she became a pupil at the ‘Institution Royale de Musique classique et religieuse’ in Paris... on the trial day, the French examiners found that the English child was a very exceptional student, and abnormally gifted with a silvery, bell-like, clear and ringing voice, which, after studious cultivation, became a fixture and a lifelong possession. (Gigliucci 1910)

[The Hull Packet noted in September 1835:] Miss Clara Novello sang ‘Agnus Dei’ most sweetly; her voice was soft as the tones of musical glasses, yet full of expression. [Note that Benjamin Franklin’s Glass Harmonica couldn’t produce a vibrato.] (Reviewer, Hull Packet, Messiah at York Musical Festival 1835)

[An earlier issue of the same journal praises her] purity of tone and chasteness of style, which have so frequently called forth our eulogiums. (Reviewer, Hull Packet, Yorkshire Musical Festival Concert 1835)

[She is quoted in Clara Novello’s Reminiscences on being chosen by Rossini in 1842 to sing his Stabat Mater at Bologna, with Ivanoff, Belgiojoso and Antoni.] Afterwards Rossini used to rehearse us, the quartet especially, in ‘Quando corpus’, which soon went as smoothly as an accordion. (Gigliucci 1910)

[Schumann, in his Music and Musicians of 1854, described Novello’s voice:] For years I have heard nothing that has pleased me more than this voice, predominating over all other tones, yet breathing tender euphony, every tone as sharply defined as the tones of a keyed instrument. (Schumann 1854)

The voices of six other non-vibrato singers were clearly free of vibrato:

[The Times critic praised the bass Superchi in February 1847 as follows:] It is impossible for a singer to be more free than Superchi from this defect of his predecessor [this was Fornasari, who was widely faulted for his tremulousness]. His notes are as firm as possible, and his flow of song is in the highest degree smooth and even. (Reviewer, Times, La Favorita at Her Majesty's Theatre 1847)

[A Manchester Guardian review in November 1874 rated Melita Otto-Alvsleben highly.] The purity of her tone is delightfully in harmony with the luscious sequences and symmetrical form of Rossini’s later arias. Singing more absolutely perfect in tune we think we have never heard. We are not certain, however, whether, in these days of the vibrato, so much used and abused as to be almost universal, this very steady purity of tone does not give to her singing a certain coldness to ears depraved by listening to singers who indulge in the vicious practice which is so prevalent. Whether or not, we hope that we shall still be able to count upon her as representing a school of singing where purity of tone and truthfulness of intonation were of, at least, equal importance with vocal facility, and far above mere meretricious trickery of whatever kind.’ (Reviewer, Rossini’s Stabat Mater at Mr. C. Halle's Grand Concert 1874)

[The Examiner approved of Madame Robinson on her début in 1880.] There is no suspicion of tremolo in the production, the tone being as round and even as an organ diapason. (Reviewer, Examiner, Fidelio 1880)

[The New York Times welcomed the tenor Wladyslaw Mierzwinski on his début in October, 1882.] He won success in the first act by some brilliant vocal efforts which fairly excited the audience to an unusual pitch of demonstrative applause. There is no question as to his voice. It is brilliant, clear, and he can use it without resorting to any tricks. There is no vibrato in it, his tone being as steady as a mechanical instrument. (Reviewer, New York Times, William Tell at the Academy of Music 1882)

[The Pall Mall Gazette reported on Giuglini in July 1884.] That incomparable tenor sang with the firmness and smoothness of a clarinet, and always with the same striking effect. (Reviewer, Pall Mall Gazette, Traviata, Covent Garden 1884)

[The Brooklyn Daily Eagle commented in December 1890 that the high notes of Mr. Heinrich Gudehus] were as clear and true as those of an instrument. (Reviewer, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Lohengrin at the Met 1890)

The other side of the story

I’ve noted that only about 7% of notices approved of vibrato, generally when used selectively to express intense feelings. Further, continuous vibrato was occasionally praised where the oscillation was a slight shimmering. Such singers were also described as possessing ‘natural vibrato’ or as having ‘tears in the voice’. A singer whose voice comes closest to this quality is Jeni Melia, except that she is a soprano, not a contralto. Jeni specialises in lute songs and folk ballads. You can download (and pay for) her album The Last of Old England from Magnatune (Melia and Goodwin 2005). The critic Henry Chorley, writing in his Thirty Years Musical Recollections of his opera reminiscences for the year 1847, commented on the singing of contralto Marietta Alboni in the following terms.

Hers was a rich, deep, real contralto, of two octaves from G to G – as sweet as honey – but not intensely expressive; and with that tremulous quality which reminds fanciful speculators of the quiver in the air of the calm, blazing, summer’s noon.– I recollect no low Italian voice so luscious. (Chorley 1862)

Eight further notices either fault Alboni’s vibrato, or commend her for its absence:

... we must enter our protest once more against this lady’s imitation of the infirmity of age—against that tremulousness of voice which many of the Italian singers of the present day affect. This is what they call vibrazione di voce—a vice which can only be accounted for by supposing that the constant practice of singing occasionally damages the brain. (Reviewer, Examiner, Fourth Concert of Ancient Music under the Direction of the Prince Albert 1848)

The tones of her voice were meltingly soft, yet round and full, and her sustained notes were maintained with the utmost ease. There was no apparent striving—not the slightest tendency to unsteadiness, or loss of pitch... The execution was as exact and true to time as though performed by a piece of mechanism, while the intonation was as clear and ringing as a series of chimes. (Reviewer, Glasgow Herald, Mademoiselle Alboni's Concert 1848)

Alboni sang Handel’s air, from Rodelinda if our memory serve us... the style in which she sang it appeared to us cold and almost listless; and besides there was an artificial tremolo employed throughout, which struck us as inappropriate. (Reviewer, Berrow’s Worcester Journal, The Musical Festival 1848)

... It is, however, the initiated to be enabled to discover shortcomings; and to these it was evident that Alboni’s voice and style were both susceptible of amelioration. In the former, for instance, they remarked an occasional tremulousness, which might have proceeded from physical weakness, or over anxiety. (Reviewer, Morning Post, Alboni's debut as Cinderella 1851)

... ’Ah! non credea’, and ‘Ah! non giunge’ from the Sonnambula ... The introductory Andante was delivered with a melting, tremulous, and yet chaste pathos, in which there was no sentimental weakness, but a sustained purity of style, and a complete realization of that tearful quality of natural tone which we have heard ascribed to her. (Reviewer, Musical World, Alboni in America 1852)

Any voice superior in quality to it, betwixt F and F, we do not recollect; —since that octave has all Mdlle. Alboni’s luscious sweetness without her tremulousness11 , and is twice as powerful as hers [Madame Amedei’s]. (Reviewer, Athenaeum, Madame Amadei The London Orchestra concert 1854)

The clear rich tones of Madame Alboni are given with no less power, facility of execution, and purity of style than they were many years ago. Her steadiness of enunciation is an additional qualification, and contrasts favourably, in our opinion, with the tremolo characteristic which is so often associated with high cultivation. (Reviewer, Bradford Observer, Full Dress Grand Concert 1861)

[The Sun, New York, quoting from the London Daily Telegraph:] Although she is more than 60 years of age, the voice of the great songstress is practically unimpaired by time. Thanks to her perfect method of singing, her voice even now betrays none of that detestable tremolo which is the pervading defect of the modern school, and the superb tones of her incomparable contralto had the effect of the notes of an organ in Rossini’s ‘Agnus Dei’, which no artist has ever rendered so well. Mme. Alboni’s singing is a lesson in a now bygone school. (Reviewer, Sun (New York), Alboni's Voice as Good as Ever 1887)

Alboni’s vibrato must have been very narrow to have generated critiques ranging from brain damaging vibrazione di voce to a laudable absence of the detestable tremolo, suggesting that critics c.1850 were very severe on even the slightest suspicion of unsteadiness. It is of interest that, while Chorley praised Alboni and one other vibratoist, Angiolina Bosio, his Recollections convey clear disapproval of six further vibratoists, namely, Meric Lalande, Rubini, Fornasari, Tamberlik, Anna De La Grange and Maria Spezia. Perhaps, for him, it was a matter of degree – a barely detectable shimmering would have been OK, but not a detectable wavering.

The fact remains that many vibratoists continued to sing their way, in the teeth of strong critical opposition. So far, I have been unable to find accounts from any commentators, whether singers or not, justifying the trend towards vibrato singing, apart from Emma Calve’s praise for ‘the thrill’, already noted. If they could speak, they might say something like: ‘I am a free, creative artist. When I sing and act, the vibrato helps me to convey my intense feelings. My way is the future. Vibrato and the new romantic music go together. These hostile anti-vibrato notices are just symptoms of conservative resistance to change’. Indeed, a few critics went so far as to concede that vibrato might have helped singers like Rubini and Tamberlik to achieve dramatic truth, possibly at the expense of vocal beauty. Also, some disapproving reviewers admitted that audiences often applauded vibrato. For example, Rosina Carandini’s singing was described thus:

The voice is perfectly under command, and is used, as a rule, with remarkably good taste. There seems to be a tendency to indulge in a tremulousness of tone, when much feeling is desired to be expressed, which is very easily, by indulgence, made a blemish on pure expression, but which, it must be admitted, is often very popular with mixed audiences. We do not believe that Miss R. Carandini needs any such aid to even popular effectiveness; and it would be regrettable if the tendency should be encouraged. (Reviewer, Otago Daily Times, The Carandini Concerts 1867)

Two case studies

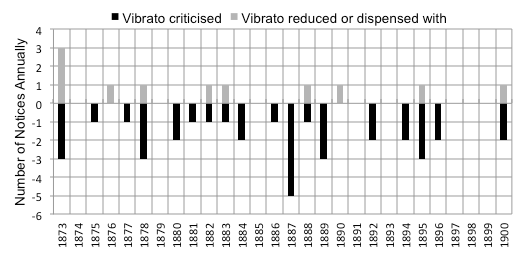

I mentioned that there is a problem with the list of supposedly non-vibrato singers in the Wobblers article I quoted from earlier. Here is a table (Fig.3) listing all the singers mentioned, in date of birth order. I’ve included the number of reviewers’ notices criticising these singers’ vibrato, or praising the lack of it, plus recording dates in some cases.

The problem is that many of these singers, certainly those in the bottom half of the list, attracted some unfavourable notices for their vibrato. We also have some of their recordings, all of which display some vibrato. The claims of the article’s author appear to be inconsistent with some reviews and with the available recordings. There might be 3 reasons for this: (1) By 1890, most singers were using at least a narrow vibrato, which I have shown was quite acceptable to many, perhaps even the author of this article, although not the wider tremolo; (2) Around 15 years elapsed from 1890 until the recordings were made, during which time the singers probably adjusted their vibrato levels to match the wider oscillations customary in the first decade of the 20th century; and (3) The recorded vibrato might in a few cases be age related.Fig. 3: Notices and Recordings of Alleged Non Tremolo Singers12

Singer d.o.b. Recording Vibrato Notices Non-vibrato Notices Giovanni Matteo Mario 1810 3 (selective) 9 Clara Novello 1818 - 0 1 + Schumann ref Jenny Lind 1820 - 1 (occasional) 3 Antonio Giuglini 1829 - 0 3 Therese Tietjens 1831 - 0 2 Giusseppe Fancelli 1833 - 0 1 Sir Charles Santley 1834 1913 3 4 Zelia Trebelli 1838 - 1 3 Christine Nilsson 1843 - 0 4 Adelina Patti 1843 1905 4 (2 selective) 15 Italo Campanini 1845 - 1 (selective) 9 Dame Emma Albani 1847 1903 37 10 Edouard de Reszké 1850 1903 1 (nearly free!) 3 Jean de Reszké 1853 1901 2 8 Marie Basta-Tavary 1856 - 3 0 Lillian Nordica 1857 1907/11 1 2 Zélie De Lussan 1861 1903 5 1 Margaret MacIntyre 1865 ? 16 1

Let’s look at two important examples from the list, both famous divas:

Adelina Patti

At the start of her career, Patti received the only really hostile reviews in her whole life, mainly from Henry Chorley of The Athenaeum and the Musical Examiner (Klein 1920). He objected to her fatigued voice and vibrato. And, right at the end of her career, a noticeable vibrato is evident from her 1905 and 1906 recordings. But I have also identified 15 reviews praising her vibrato-free voice. This is puzzling. I’m seeking additional data to throw more light on the question. Meanwhile, I leave Patti with a review dated October 5, 1883, which is consistent with the available evidence and has the ring of truth:

We have been so often disgusted by the abuse of the vibrato that we sometimes forget how effectively it may be used as an occasional ornament. Madame Patti illustrates this by frequent, but never tedious employment, and she has never permitted it so to affect the perfect control of her voice as to deprive her of the power of sustaining sounds with a steadiness and purity such as we too seldom listen to. (Reviewer, Manchester Guardian, Messrs. Harrison's Concert, Free-Trade-Hall, Manchester 1883)

Emma Albani

Dame Emma Albani was almost as famous as Patti, with a huge audience of devoted fans in four continents (MacDonald 1984). As you have seen from Fig. 3, there are four times as many negative as favourable notices on her vibrato singing. Here are three of the positive reviews.

In this scena [mad scene in last act] she was sparing of the tremolo, which so often spoils her best efforts; and showed that, without resorting to it, she can display pathos. (Reviewer, Observer, Royal Italian Opera, Lucia di lammermoor 1873)

Her beautiful voice was in the finest order; hardly any trace of tremolo was apparent. (Reviewer, Observer, Royal Italian Opera, I Puritani 1876)

The old tendency to scoop at the cadences was again made manifest, but the tremolo appeared less evident than usual. (Reviewer, Leeds Mercury, Hereford Festival, Messiah 1900)

And some unfavourable ones:

[London correspondent of the Sydney Morning Herald:] The passionate dramatic style required for the stage is utterly unsuited to the pure, noble simplicity of sacred music; and I noticed that all these opera singers, from continually declaiming in the strained accents of love or despair, have acquired a tremulous quaver in the voice. This was especially remarkable in Albani’s rendering of ‘Angels ever bright and fair’, where not one of the sweet long-drawn notes was held steadily for two seconds. (Reviewer, Sydney Morning Herald, Odds & Ends from the Old Country, triennial celebration of the Handel Festival 1880)

… she [Albani] appears unable to sing without using the vibrato to an unpleasant extent. (Reviewer, Chicago Daily Tribune, Music and Drama, Faust, Auditorium 1889)

Mdme. Albani indulged rather freely in an obnoxious vibrato. (Reviewer, Leeds Mercury, Messiah, St. George's Hall, Bradford 1892)

... very much marred her rendering of ‘O come unto Him’ by persistent and excessive vibrato. (Reviewer, Bristol Mercury and Daily Post, Messiah, Birmingham Festival 1894)

Fig.4 Reviews of Albani’s Vibrato or the Lessening of It

Albani’s reviews are displayed on a time line at Fig.4. This shows that favourable and unfavourable notices are evenly distributed throughout her career, suggesting that her vocal timbre and style may not have changed much. Such critical extremes tell us more about the varying preferences of reviewers than differences in her performance style. In any case, most favourable reviews admit some vibrato previously, or a reduction of it.

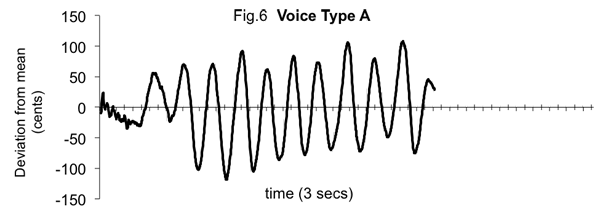

But, it so happens we have a recording of Albani’s Angels Ever Bright and Fair. This and other of her recordings have been put into the public domain. At this point, I invite the reader to download and play Angels Every Bright and Fair from an excellent, well-documented, website www.collectionscanada.gc.ca (Albani 1903)