Formal Syntax and Deep History

Posted on 18 February 2021

Prof. Giuseppe Longobardi (Dept. Language and Linguistic Science), in collaboration with a team of researchers including Prof. Cristina Guardiano (University of Modena and University of Reggio Emilia, Italy), and two former members of Professor Longobardi’s ERC grant group at York, Dr Monica Irimia and Dr Andrea Ceolin (University of Reggio Emilia, Italy), has recently published a new article ‘Formal Syntax and Deep History’ in the journal Frontiers in Psychology. The paper focuses on the reconstruction of prehistoric language families from the syntax of their modern descendants.

‘Formal Syntax and Deep History’ shows that syntactic traits provide insights into deep-time language history.

Philologists and historians have long tried to use languages to cross the boundaries between recorded history and prehistory; they compared similar words from different languages to assemble these into families, which point to common ancestors, so-called protolanguages (e.g. proto-Indo-European) spoken in the far past. This has unearthed unsuspected relations between distant peoples/cultures: Western Europe with, for example, the ancient Buddhist culture of Chinese Turkestan.

However, beyond a period variously estimated between 5 and 10 thousand years, common ancestry among vocabularies becomes irretrievable. This has been frustrating for linguists, increasingly so since 20th-century genetics came to complement linguistics and archaeology in reconstructing populations’ migrations and contacts. Genetics has produced time-deeper hypotheses about the origin and movements of modern humans, raising new questions for linguistics itself. But how can you investigate issues on the dispersal of mankind that go back 30 millennia if words change much more quickly?

We took the model of population biology very seriously and transferred it not to the study of visible words but of syntactic rules, modelled as ‘invisible’ computations of our mind in modern cognitive science. This trend, inspired by biologist Eric Lenneberg and linguists Noam Chomsky and Morris Halle in the 1960s, has only later turned to study how languages differ in syntactic rules. Even until now, linguists have neglected the potential of syntax for historically comparing different language families.

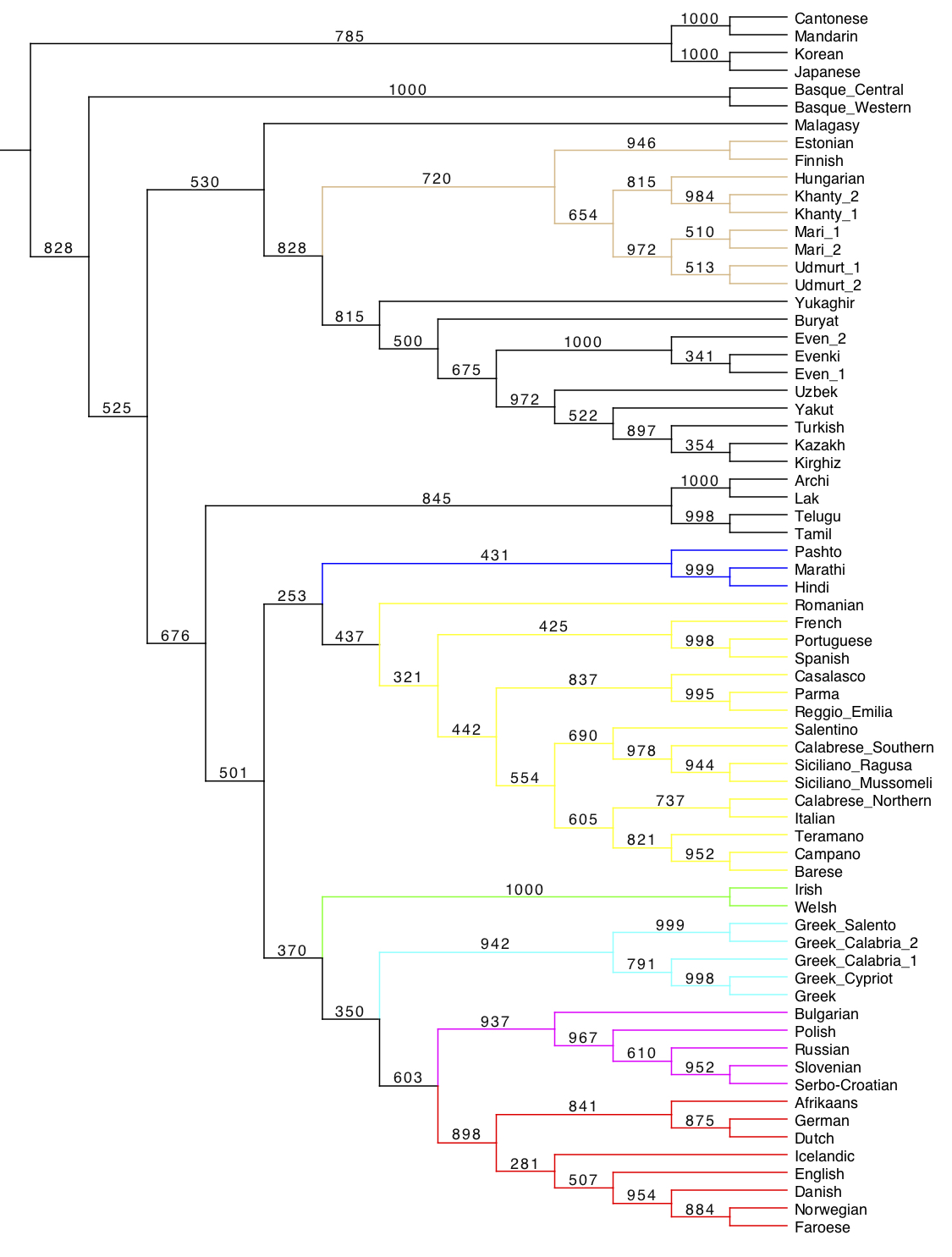

We show that a cognitive science of language can break through the time barriers of classical prehistory studies: comparison of vocabularies or sounds becomes uninformative beyond hinting at the existence of 13 separate families of languages, which (along with a few more) have contributed to peopling Eurasia. We found that mathematically modelling syntactic diversity can reduce these languages into less than 13 families: this needs further on-going investigation, but is already much more compatible with the genetic and palaeo-anthropological evidence of few, even just two, main events of prehistoric peopling of the Eurasian continent.

Genetic markers in biology have surprisingly opened the possibility of re-addressing some old questions: where do we humans come from? How different are we? Discoveries like those of this article pave the way to the use of cognitive science in the new exciting field of deep human history.

“Recently a lot of talk about the origin of human language has become fashionable again, after the topic had been banned as non-scientific for 150 years. Unfortunately, though, most of this new meritory discussion is based on very indirect inference from the current properties of the general human language capacity, and there is little, if any, archaeological or palaeogenetic evidence for prehistoric languages and their structure. At York and Reggio Emilia we are beginning to address such issues from the bottom: what kind of reconstruction of the prehistory of languages can we attain by comparing present-day languages in their diversity? Can we establish relations among ancient populations through their grammars? It’s all new and exciting, we don’t know how far back in the past we can eventually reach…” - Prof. Giuseppe Longobardi, Dept. Language and Linguistic Science

To read the article in Frontiers in Psychology: Formal Syntax and Deep History