Evidence summary

Reducing lifestyle risk behaviours in disadvantaged groups

Scoping review of systematic reviews with interactive evidence maps

- Overall and healthy life expectancy differs between the most and least disadvantaged areas of England. Much of this gap is attributable to differences in rates of heart disease, respiratory diseases and lung cancer, conditions all related to lifestyle risk behaviours.

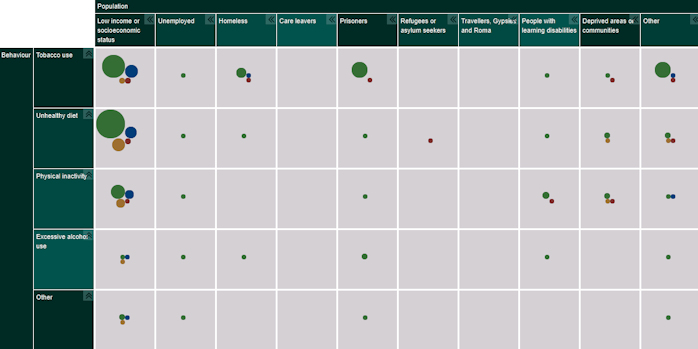

- We mapped the systematic review evidence on reducing lifestyle risk behaviours among disadvantaged groups or in disadvantaged communities.

- We included reviews of empirical evidence published from 2009 to October 2020 that focused on one or more of four common lifestyle risk behaviours (tobacco use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol use) among disadvantaged groups.

- We found 92 relevant reviews. Interactive evidence maps of this evidence can be explored here.

- We found no review evidence on interventions targeting refugees/asylum seekers, Travellers/Gypsies/Roma, or care leavers.

- Reviews of alcohol interventions were scarce across all disadvantaged groups.

- We make research recommendations about how existing evidence might be brought together and how the observed gaps in the evidence base might be filled.

Background

The gap in life expectancy between the most and least disadvantaged areas of England is 9.4 years for males and 7.4 years for females, and there is a 19-year difference in healthy life expectancy. Much of this is attributable to differences between areas in rates of heart disease, respiratory diseases and lung cancer, all conditions related to lifestyle risk behaviours such as tobacco use.(1)

Socio-economic inequalities exist in smoking, physical inactivity and dietary risks (2-4) and risk behaviours are particularly prevalent in certain groups. For example, high levels of smoking have been reported among UK prisoners(5) and US homeless people.(6) Evidence indicates low levels of physical activity in UK prisoners, and high sodium and fat intake in prisons worldwide.(7) There is evidence of high levels of tobacco use in Gypsy and Traveller communities in England(8) and high prevalence of smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity and alcohol consumption among Roma communities.(9) Alcohol use and smoking are reportedly more common in unemployed people,(10) and a study of almost 8,000 job-seekers in Germany additionally found high prevalence of physical inactivity and very low consumption of fresh fruit or vegetables.(11) People with learning disabilities have been found to have low levels of physical activity, with just 9% of almost 3000 participants in one systematic review achieving at least 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity a week.(12)

Health promoting environments which support healthy lifestyles in disadvantaged groups are essential if improvements in their health are to match and outstrip those in the wider population.

Aims

We aimed to map the systematic review evidence on interventions to reduce lifestyle risk behaviours among disadvantaged groups or communities. This map could then be used to identify:

- Which interventions have been evaluated and implemented with which disadvantaged groups

- The potential barriers and facilitators to adopting healthy behaviours for specific groups

- Gaps in the evidence base where new or updated evidence syntheses are needed or where new primary research is required

What did we do?

We included reviews of empirical evidence published from 2009 to October 2020 that focused on one or more of four common risk behaviours (tobacco use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol use) in the following disadvantaged groups:

- People with low income or socio-economic status (SES)

- Unemployed people

- Homeless people

- Care leavers

- Prisoners

- Refugees or asylum seekers

- Travellers, Gypsies and Roma

- People with learning disabilities

- People living in disadvantaged areas or communities

Two reviewers independently screened the results of electronic database searches to identify relevant reviews.

Full details of the methods and results are available elsewhere.(16)

What did we find?

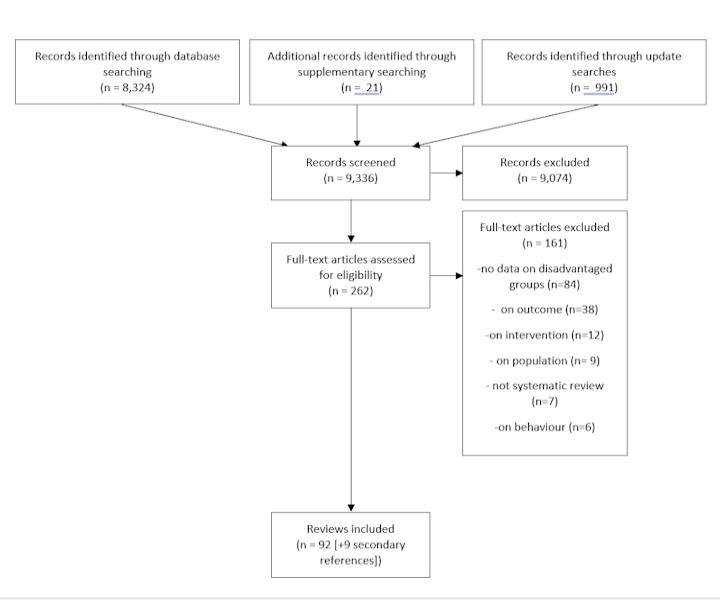

We identified a total of 9,336 records from the literature searches. Ninety-two reviews were included. See below for the flow of records through the selection process.

Interactive maps of the included review evidence |

|---|

|

The three links below will open interactive evidence maps, where you can see the pattern of results and explore the reviews in greater detail. To view the maps, download them below. They will open in your browser as interactive pages.

Simply click the “About” tab above each map for information on how to use the interactive features. |

Characteristics of the included reviews can be explored in the interactive evidence maps (see box). These maps suggest:

- Most reviews focused on groups with low income or low socio-economic status (n=68; 74%). Diet (n=38), tobacco use (n=31), and to a lesser extent, physical activity (n=22) were explored.

- The next largest group of reviews included prisoners (n=14; 15%), most of which focused on smoking, either alone or alongside other risk behaviours (n=12).

- Similarly, most reviews on homeless people were on tobacco interventions or barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation (n=8/10).

- Reviews focusing on people with learning disabilities (n=9; 10%) were specifically concerned with barriers to physical activity or interventions to increase physical activity (n=7).

- For almost every combination of population and risk behaviour, the majority of reviews focused on interventions targeted at disadvantaged groups (as opposed to population-level interventions or barriers/facilitators).

- Reviews of interventions delivered at a population-level (e.g. fiscal measures, legislation, mass media campaigns) typically focused on the effects for low income/socio-economic groups. The effects of these interventions among other disadvantaged groups was largely overlooked.

The maps also revealed a number of gaps in the evidence:

- No reviews looked at care leavers or Traveller/Gypsy/Roma communities.

- Evidence on refugees and asylum seekers was limited to two reviews of barriers and facilitators to behaviour change both of which focused solely on diet.

- Relatively few reviews address unemployed people, with just one broad scope review(17) specifically focusing on this group.

- The review evidence on excessive alcohol use is sparse in comparison with the other three risk behaviours. For example, there were no reviews targeted at alcohol use in disadvantaged areas.

- Most reviews evaluated individual-level interventions (n=50) with few focusing on environmental change to support healthy lifestyles.

- The total number of reviews addressing barriers/facilitators to behaviour change across all disadvantaged groups is relatively small (n=16).

What are the limitations?

There is no single commonly accepted definition of ‘disadvantaged groups’ and some groups (e.g. indigenous communities, people experiencing mental illness) lay outside our scope.

As the aim of this review was to map the extent and nature of evidence available, reviews were not selected on the basis of their methodological quality. Consequently, the map includes high and low quality evidence.

What next?

This scoping review has identified several gaps in the evidence that could be explored further. This might include:

- Scoping the primary research literature on refugees/asylum seekers, Travellers/Gypsies/Roma, care leavers, and unemployed people to investigate whether these groups have been overlooked by systematic reviews, or if the lack of reviews simply reflects a lack of primary studies.

- A systematic review of alcohol interventions across all disadvantaged groups. This might be particularly informative where there is no recent review of the subject (e.g. among homeless populations).

Where specific groups and/or behaviours have been reviewed multiple times the evidence could be brought together. This might include:

- An overview of systematic reviews (for example, diet, smoking, and physical inactivity in low income/SES groups). Such an overview should emphasise higher quality evidence (through critical appraisal of reviews and possibly by excluding the poorer quality SRs identified in this mapping exercise).

- An overview of reviews addressing barriers/facilitators across all disadvantaged groups. This could potentially identify common predictors across groups and factors that are unique to specific groups. The people and organisations who try to develop appropriate interventions for disadvantaged groups can also face extraordinary challenges. Any new systematic review should therefore focus on barriers to the development and implementation of interventions as well as barriers to behaviour change among the groups being targeted.

References

1. Public Health England. Health profile for England 2019: 9 key points from our 2019 update. London: Public Health England; 2019 [Available from: https://publichealthengland.exposure.co/health-profile-for-england-2019]

2. NHS Digital. Statistics on obesity, physical activity and diet, England, 2019. Leeds: NHS Digital; 2019 [Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-obesity-physical-activity-and-diet/statistics-on-obesity-physical-activity-and-diet-england-2019]

3. Osborne B, Cooper V. Health survey for England 2017: adult health related behaviour. Leeds: NHS Digital; 2018.

4. NHS Digital. Statistics on obesity, physical activity and diet, England, 2020. Leeds: NHS Digital; 2020.

5. Public Health England. Reducing smoking in prisons: management of tobacco use and nicotine withdrawal. London: Public Health England; 2015.

6. Baggett TP, Rigotti NA. Cigarette smoking and advice to quit in a national sample of homeless adults. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:164-72.

7. Herbert K, Plugge E, Foster C, Doll H. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet 2012;379:1975-82.

8. Peters J, Parry GD, Van Cleemput P, Moore J, Cooper CL, Walters SJ. Health and use of health services: a comparison between Gypsies and Travellers and other ethnic groups. Ethn Health 2009;14:359-77.

9. Cook B, Wayne GF, Valentine A, Lessios A, Yeh E. Revisiting the evidence on health and health care disparities among the Roma: a systematic review 2003–2012. Int J Public Health. 2013;58:885-911.

10. Henkel D. Unemployment and substance use: a review of the literature (1990-2010). Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2011;4:4-27.

11. Freyer-Adam J, Gaertner B, Tobschall S, John U. Health risk factors and self-rated health among job-seekers. BMC Public Health 2011;11:659.

12. Dairo YM, Collett J, Dawes H, Oskrochi GR. Physical activity levels in adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Prev Med Rep 2016;4:209-19.