Patterns of Pilgrimage in England c.1100-c.1500

Interior Pilgrimage: Anchorites, Mystics and the Monastic Orders

Pilgrims en route to heaven

Scale of Perfection

There is no need to run to Rome or Jerusalem to look for [Jesus] there, but turn your thought into your own soul where he is hidden.

Walter Hilton, Scale of Perfection, Book I.49, 5

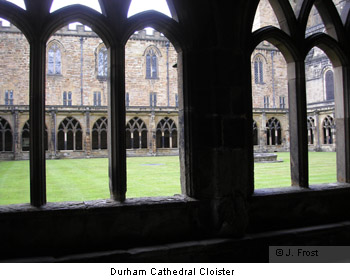

From the fourth century onwards Christians who left homes and families, either to live as solitary hermits and anchorites or as part of monastic communities, were regarded as embarking upon a highly specialised expression of the pilgrimage of life, in which inner journeying took priority (see Early Christian Tradition). They entered into a life of prayer and discipline, experiencing exile on earth in order to win citizenship in heaven. Their spiritual 'journey' required that they remained still physically in order to journey inwardly and stability formed an essential part of the calling of monks, nuns and anchorites. In many monastic texts commitment to remaining within the cloister is equated with obedience, though in practice the authorities often found this hard to enforce.

The period 1100-1500 saw significant developments in monastic and anchoritic practice in England as elsewhere. Monastic orders multiplied, though not without controversy and challenge, and women increasingly adopted the anchoritic life, often enclosed in cells constructed alongside churches. Texts written for their guidance show that they were encouraged to adopt a regular pattern of prayer, to contemplate Christ's life and suffering and to imitate role models such as the Desert Fathers and Mothers and the Virgin Martyrs such as St Katherine, St Margaret and St Juliana.

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the writings of the English Mystics explored the possibility of anticipating the joys of heaven through intimate inner encounter with God. The forms taken by such inner journeys were many, including contemplative prayer, dreams, visions and the sanctified use of the imagination through meditation on the scriptures.

Towards the end of the fourteenth century, lay Christians were also seeking ways to add contemplative prayer to their life of active service in the world. Meditation on the scriptures of the kind recommended in the pseudo-Bonaventuran Meditations on the Life of Christ offered pilgrimages of the imagination in which they could enter into the events of the Nativity and the Passion. For them too inner journeying through prayer and meditation increasingly offered the hope of direct experience of God.

Dee Dyas