Patterns of Pilgrimage in England c.1100-c.1500

'Moral' Pilgrimage: The Daily Christian Life

Pilgrims en route to heaven

In the later Middle Ages, as in earlier centuries, 'Moral' Pilgrimage (a daily life of obedient service to God and others in the place of one's calling) was the one form of pilgrimage essential for all Christian believers, in contrast to the voluntary devotion represented by journeys to holy places (see Place Pilgrimage) or through the religious life (see Interior Pilgrimage). Since the exile of humankind from the Garden of Eden was believed to result from the disobedience of Adam and Eve (see The Bible), those who wished to reach the heavenly homeland had to be prepared to seek forgiveness for sin and commit themselves to a life of obedience, serving God and others.

1 Peter 2:11

Dearly beloved, I beseech you, as strangers and pilgrims, to refrain yourselves from carnal desires which war against the soul.

1 Peter 2:11

Journeying to heaven was, in essence, journeying back to God, overcoming the spiritual separation caused by sin. The Christian pilgrim through life was, however, still trapped in a fallen world, confronted by sin, exposed to temptation and often unable to clearly discern the will of God. Progress therefore was frequently erratic, with individuals demonstrating lack of understanding and falls from grace, a pattern illustrated in the late fourteenth-century poem Piers Plowman. The pilgrim's great enemies were the Seven Deadly Sins, ready to waylay travellers on the road to heaven, yet there was also the hope of forgiveness, ministered in the Middle Ages through the sacrament of Penance. Christians needed to be alert and to make use of the resources for the journey offered by the Church.

While some elements of the Christian life remained relatively constant, perspectives on others changed and developed radically during the Middle Ages. To some extent, each generation had to wrestle afresh with how to respond to the challenge of living life as a pilgrimage. Changes in understanding exercised a profound effect on the structures and practices of the Church and religious art and literature.

Life as Journey

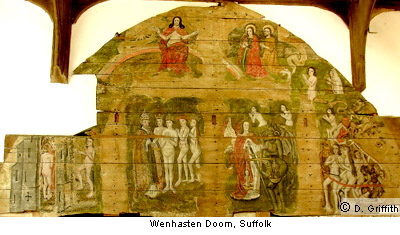

Late medieval society was pervaded by a strong sense of life on earth as a journey with eternal significance. The late fourteenth-century poem, Piers Plowman, opens with a vision of the universe which provides a vivid and challenging perspective on daily life. Heaven is imagined on high, reserved for the redeemed; Hell's dungeon is below, ready for those whose sins weigh heavy upon them. In between lies the world of human experience, full of trials and temptations, where men and women must constantly make choices which will decide their eternal destinies. The teaching of the Church through sermons, sacraments, art and literature, constantly reiterated that life was short and transitory: ahead lay death, God's judgement on the life of each individual, and an eternity spent in Heaven - or Hell.

In the New Testament Jesus Christ is shown describing himself as 'The Way, the Truth and the Life' (John 14:6). The core requirement for the would-be pilgrim wishing to reach the Heavenly Jerusalem, was to imitate Christ, obeying God, resisting temptation and using their talents and resources to serve others, whether as humble labourer, lady of the manor, monk, craftsperson, merchant or priest. Stability (commitment to one's calling) was fundamental; both orthodox Christians, such as Chaucer and William Langland, and the Lollard followers of John Wyclif were deeply critical of those who wandered away from their callings for whatever reason.

The Church constantly emphasied the dangers of sin, the need to resist temptation and the distractions of earthly possessions. It stressed too the love shown by Christ in dying for humankind and the forgiveness which his death on the Cross made available to all. The reality of sin and the hope of forgiveness were the pilgrim's constant companions on the road as they made their way through the spiritual hazards of this world.

Resources for the Journey

Medieval Christians were not expected to pursue the pilgrimage of life alone or unaided. Both the structures and the culture of the Church offered a great variety of resources to sustain them on their journey. At the same time, every individual was ultimately accountable and responsible for the fate of their soul.

The Christian Community

The Christian community provided the context in which individuals could learn and support each other. It incorporated both 'religious' - whether monks, nuns, priests or friars - and lay people. It had a specific local expression in the form of the local parish but also embraced all of Christendom. It included not only every age, background and level of education, but also had a special place for the departed, whether local loved ones, or the heroic saints.

The Teaching of the Church

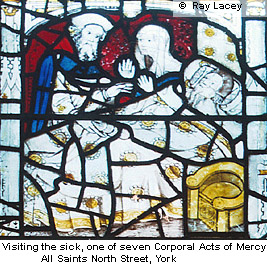

This diverse community was held together by a body of teaching and shared beliefs and values. The later medieval church deliberately promoted a culture of religious education, not limited to instruction in the catechism, but present in preaching, drama, religious literature and art. This emphasis came in part from the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) which required annual confession for adult members of the church and therefore made it necessary for all to be taught about sin, forgiveness and daily obedience to God.

Personal Spiritual Life

We have very few 'accounts' of personal experience and those which do survive tend to be composed by exceptional figures. Moreover such experiences were often expressed in highly conventional language and imagery. At the same time sermons and literature and affective art testify to a widespread desire to evoke a heartfelt response in individuals. Alongside the attempt to promote moral behaviour, the church provided the means for individuals to develop personal devotional lives. This 'private' aspect of the pilgrimage of life is often glimpsed only through the paraphernalia of devotion, such as prayer beads, indulgences, Books of Hours and images.

Miriam Gill and Dee Dyas