Patterns of Pilgrimage in England c.1100-c.1500

Pilgrimage in Medieval English Literature

Introduction

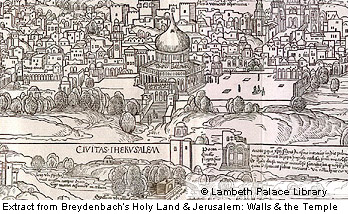

Pilgrimage is an important motif in a wide range of medieval texts. It occurs in three principal ways, which are not necessarily exclusive and which frequently overlap: as an image of the Christian journey through life, an actual, physical journey to a sacred location, and an internal, spiritual experience. A text may describe a pilgrim - or group of pilgrims - travelling to Rome, or Jerusalem, or any of a number of shrines, in England or abroad, for a mixture of motives, some pious, some less so (see Place Pilgrimage). Another may chart the life of a Christian from birth to death as a pilgrimage towards salvation (see Moral Pilgrimage) or offer an inner exploration of the progress of the soul (see Interior Pilgrimage). In some of the greatest works of this period, such as Guillaume de Deguileville's Pilgrimage of the Lyfe of the Manhode, Piers Plowman and Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, external and internal journeys are intertwined. There are recurrent characteristics of the topic which help us identify texts as 'pilgrim texts' even while they also belong to other genres, for the subject of pilgrimage overlaps with categories as various as drama, satire, romance, anchoritic writings and mysticism, the literature of dream visions and of courtly love.

The Pilgrimage of the Lyfe of the Manhode, Piers Plowman and the Canterbury Tales

The Pilgrimage of the Lyfe of the Manhode

De Deguileville presents an allegorical pilgrimage, in which the dreamer, having seen the heavenly city, the celestial Jerusalem, in a dream, conceives a desire to reach it. The poem describes the whole of a soul's life on earth. He is born, experiences the sacraments in baptism, and sets out with a pilgrim's scrip and staff. He encounters friends and foes - especially the fearsomely armed Seven Deadly Sins, and later both Satan and Heresy. Early on he is dressed in armour as a knight - as if the journey is to be a chivalric quest with battles, but he finds these too heavy and awkward, so Grace allows him to remove them and set out as a simple pilgrim. There is a shift here from military symbolism, with the soul setting out armed by the symbolic armour of God replaced by a more passive concept: the soul can do little for itself but needs the help of Grace and the Virgin Mary on its journey. Tossed on the sea of life, the Dreamer finds safety by entering the Ship of the Church. At the end of his dream the soul, at death, leaves the body and flies up towards heaven. The Dreamer then wakes up and finds that he is at his monastery in Chalons.

The Canterbury Tales

The most important aspect of real-life pilgrimage used by Chaucer in the Canterbury Tales is the fact that a wide variety of people, of different classes and different places might be found together on a pilgrimage. He has many story-tellers of differing class and character, and diversity, in many different forms, is the keynote of his collection. The way he exploits this fact creates a text in which he not only represents the diversity of contemporary society but also has the opportunity to depict conflict and rivalry between different trades. Famously, too, in imitating the real-life fact that pilgrims amused themselves en route by songs, musical instruments and story-telling, Chaucer offers a variety of genres and levels of seriousness and elegance. Some stories are bawdy fabliaux, some saints' lives or serious treatises.

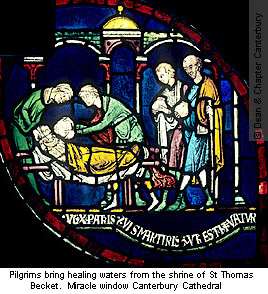

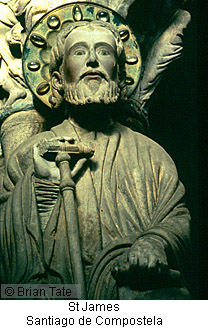

Chaucer introduces his pilgrimage by saying that people want to travel in spring on pilgrimages, especially to the shrine of St Thomas Becket in Canterbury - who has helped them when they were sick (I 18). Although this introduction, the General Prologue, mentions St Thomas, the 'hooly, blissful martyr', it makes few other allusions to the spiritual side of pilgrimage, though the narrator describes himself as setting out 'with ful devout corage' (I 21). Some of his portraits of the pilgrims mention contemporary practices of pilgrimage: the Knight's decision, for example, immediately upon returning from campaigning (against the Muslims, 'for oure feith'), to go immediately on his pilgrimage; the Wife of Bath is described as an experienced pilgrim: she has visited shrines at Rome (the apostles Peter and Paul), Boulogne (Our Lady), Compostela (St James), and Cologne (the Three Kings). Chaucer announces that his plan is for his pilgrims to tell tales both going to Canterbury and coming back to London and the Tabard Inn. But, when he died, he left his work in a set of fragments, which do not join up into a coherent depiction of journey to Canterbury.

Chaucer seems for the most part to exploit primarily the social side of pilgrimage. But he appears to have written the Parson's Tale, a treatise about sin, virtue and penitence, as a religious text to knit up the actually extremely diverse groups of tales he had already completed. In most manuscripts it appears as the last of the series. It also includes the metaphor of human life itself as a spiritual journey towards the Heavenly city of Jerusalem. There is thus a shift in tone between most of the Tales, as they have been left to us, and the Parson's Tale, which is not only religious itself but includes two passages that make the earthly pilgrimage into a symbol of the soul's journey on:

...thilke parfit glorious pilgrimage

That highte Jerusalem celestial. X 50-1.

Piers Plowman

'pilgrymes are we alle.'

[Piers Plowman, XI.240]

Pilgrimage motifs play a significant role in William Langland's Piers Plowman, a complex text which survives in several versions. The poem draws extensively on the concept of human life as a (sometimes confused and erratic) journey through the 'wildernesse' of this world, during which each individual's eternal destiny will be decided. The Prologue introduces a narrator, Will, who dreams of a field full of folk, many of whom are not pilgrims focused on reaching Heaven but wanderers who abandon their responsibilities and fail to live according to God's laws. Anchorites and hermits who stay in their cells are praised, but beggars, wanton hermits, neglectful priests and bishops, and so-called 'pilgrims' who lie about their travels are condemned. Will's quest for salvation, urged upon him by Lady Church, is a far from straightforward business, as the poem explores (and questions) the various modes of being a pilgrim available within medieval spirituality.

Much of the fascination (and frustration) of Piers Plowman arises from the multiple patterns of pilgrimage which are laid one on top of the other within the poem. The life pilgrimage of a representative human being, seeking to combine physical journeying, inner journey and moral growth, is interwoven with the journey through history of the Pilgrim Church and the contemporary Church through the annual calendar of liturgical seasons.

The poem contains fierce criticism of the majority of those who visit 'holy places.' In the Prologue the poet characterises those who travel to Rome and Compostela (two of the greatest shrines of Christendom) as liars and hypocrites (Prol. 46-9). Later, a 'palmer', festooned with relics and pilgrim badges, is encountered but, for all his 'pilgrim' credentials, he is ignorant of a saint called 'Truth'. Instead of affirming the value of 'place' pilgrimage, the poet emphasises the centrality of 'life' pilgrimage, providing a reminder of the power of the Seven Deadly Sins, the great enemies of the would-be pilgrim to the heavenly Jerusalem, and focussing on the life of daily obedience and service to the community exemplified by Piers Plowman himself.

Helen Phillips, Dee Dyas, Judith Weiss