Place and Journey in Cultures and Faiths Worldwide

'Pilgrimage' as a universal practice

The English words 'pilgrim' and 'pilgrimage' are derived from Latin via French, while their initial meanings have clearly Christian undertones (see The Origins of the Terms 'Pilgrim' and 'Pilgrimage'). There are those who therefore think that the terms should really be limited to Christianity. However, the types of phenomena referred to - such as people travelling to and returning home from places deemed to be sacred and engaging in acts of worship and faith associated with those places and the routes to them - can be found widely, if not universally, across cultures and religious traditions. Indeed, they appear applicable also (especially, in the modern day) in contexts that are not specifically or directly 'religious' or related to particular religious traditions, to the extent that it is reasonable to view the English terms 'pilgrimage' and 'pilgrims' as more or less universal.

Pilgrimage is not only a widespread and important practice in Christianity but also in other major religious traditions, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism and Sikhism. In each of these traditions, numerous important sacred centres have developed into important focal points to which the faithful are drawn, making journeys that reinvigorate their faith, visiting places associated with the spiritual presence of holy figures at the hearts of their traditions, and demonstrating their piety and faith while taking in the inspirational sights associated with their traditions. It is not, however, only in major world religious traditions that pilgrimage is a key theme; it is as prevalent in religious traditions that are specifically connected to one culture or ethnic community (for example, Shinto in Japan), and in newly formed and developed religious movements that have come into being and flourished in the modern day.

'New Age' pilgrimage

Places associated with 'New Age' spiritual movements have become focal points for the travels and practices of those seeking alternatives to traditional religion. Often such sites were associated with pilgrimage in pre-modern times, and have been co-opted by New Agers because their historical past as pilgrimage centres is thought to have imbued them with a sense of spiritual power. One example of such a site is Sedona in the USA, once a spiritual centre for Native Amerindians and now (due to its striking physical geography) a burgeoning New Age pilgrimage site. Another is Glastonbury in England, a medieval Christian pilgrimage site that in recent times has been overlaid by a variety of legends connecting it to Celtic mythology, along with New Age ideas that interpret its striking geographical setting as an indication that it is a centre of spiritual power and healing.

'Secular' pilgrimage

Sites that are of no specific religious orientation may form the focus on journeys of spiritual significance for their participants, to the extent that they may be seen as 'non-denominational' or even non-religious (or secular) pilgrimages. Memorials commemorating the dead are a prime example of this phenomenon; the war graves of Flanders and northern France have been the focus of organised pilgrimages run by bodies such as the British Legion through the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, while the Vietnam War Memorial Wall in Washington, DC, USA, which bears the names of all the Americans killed in the Vietnam War, forms the focus of both organised and individual journeys by those who lost kin or comrades in the war, and by those who wish to remember and/or commemorate the nation's loss. Among other contemporary pilgrimage events are the visits of fans (often coming more as devotees than as merely fans) to the home and grave of Elvis Presley at Graceland, Memphis, USA, especially during Elvis Presley Memorial Week around the anniversary of his death (in August 1977), a period which includes candlelit vigils and prayers. Such events are described by many participants as 'pilgrimages', indicating the universality of the activity of being drawn to places of special significance and participating in rituals, including acts of commemoration. Pilgrimage can thus be described not just as universal in religious terms but as a practice which also goes beyond the boundaries of the formally religious into secular contexts.

Extraordinary places

Pilgrimages are clearly associated with the extraordinary; it has often been argued that a key element in pilgrimage locales is that they exude a 'spiritual magnetism' that draws people to them. Sites of pilgrimage can therefore be seen as places where something extraordinary has happened or (since legends and tales of the miraculous so often are present in the frameworks of pilgrimage) places at which something extraordinary is said to have happened. Consequently, aspects of the spiritual realm are believed to become manifest in and hence accessible at a particular physical location.

Holy figures and founders

Such manifestations are not necessarily associated with apparitions, such as the Virgin Mary, but can also be linked to holy figures and founders, whose traces and footsteps may form the impetus for the formation and creation of sacred geographies that become the framework of pilgrimages, as with the Buddha's footsteps, in terms of his passage through life. The most important Muslim pilgrimage, the hajj, is also associated with the footsteps and activities of a holy figure, in that it replicates the farewell pilgrimage made to Mecca by the prophet Mohammed just prior to his death in 632CE. Pilgrims on the hajj follow in his footsteps and undertake activities he is said to have performed during this farewell pilgrimage.

Relics

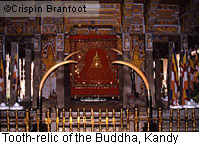

Sometimes such manifestations of the sacred are associated with relics of the holy - a common theme in Christianity, where relics of saints (whether actual or rumoured) may be the focal point of pilgrimage centres or provide the impetus that initially sanctifies a place and draws pilgrims there. Relics, too, are commonly found in and became the focal point of important Buddhist pilgrimages.

Places, landscapes and geographical features

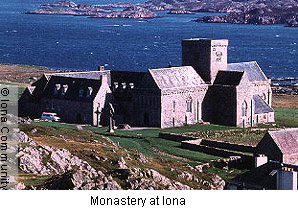

Pilgrimage places are generally marked out by the presence of striking physical constructions - temples, shrines, churches - and their accompanying objects (icons, statues, tombs of holy people) that mark out the physical presence of the sacred and that generally inspire - and are intended to inspire - a sense of awe in participants. The great cathedrals at pilgrimage centres such as Santiago de Compostela and Canterbury, prominent Buddhist temples such as the Mahabodhi temple at Bodh Gaya, and mosques at major Muslim pilgrimage sites, all speak of a grandeur that articulates in physical form the believed spiritual power of the place.

Yet, despite the visual importance and potent attraction of such physical buildings at pilgrimage sites, one should not assume that pilgrimage sites necessarily have to have large or awe-inspiring buildings at them. Nor do all pilgrimage sites necessarily focus on constructed sacred buildings or depend on legends or the acts of humans to turn them into especially holy places. The emphasis in Hindu culture on crossing places such as rivers, as pilgrimage sites, illustrates this point: natural phenomena and remarkable geographical landscape features may in and of themselves provide the impetus for the formation of a pilgrimage site, and serve as the magnet drawing people to them.

The significance of place and journey

What remains constant is the notion of people being 'drawn' to places. Factors include legends and the expectation of miracles, narratives marking places as the locus of sacred journeys by significant religious figures, signs (for example, relics and icons) manifesting the presence of a sacred being or indicating the intersection of the spiritual and the physical realm, and the capacity of sites, places and routes to provide frameworks enabling pilgrims to articulate important messages and themes.

Distance, the international, proximity and the localised

It has been often assumed that pilgrimages must to be to 'far places'. Equally, because there are a number of extremely famous pilgrimage sites of global significance (for example, Mecca, Jerusalem, Santiago de Compostela, Bodh Gaya) that draw vast international clienteles, much understanding of pilgrimage relates to it as a phenomenon that exists at international levels. Yet to assume that pilgrimage is therefore largely a practice focussed on great and distant centres would be to misrepresent its nature. Although journey and spiritually magnetic places may be key themes, pilgrimage is also very much a local practice that may draw pilgrims from places close to its centres. Those who live in Saudi Arabia and close to Mecca, for example, may also do the hajj and regard their pilgrimages in the same light as would a Muslim from the other side of the world.

Conclusion

Pilgrimage, as a process involving journeys, sacred centres and symbolic articulations of deep religious messages, along with manifestations of localised meaning, is found - and replicated - across cultures and religious traditions, old and new. It also occurs in the secular world and the world of popular culture. In terms of its component parts - the journey and the sacred place(s) to which the pilgrim travels - it has endured as a universal practice across cultures and ages. It is found at international levels at the very core of major traditions; it appears in localised contexts through which universal themes and messages can be enacted and brought down to the level of ordinary people; it is manifested within the secular contexts of the modern world, with the universal phenomenon of pilgrimage observable even at the gravesides and homes of deceased pop stars.

Ian Reader