Surround sound

New system aids hearing test

Leading UK hospitals are using pioneering technology developed by psychology researchers at York.

The Crescent of Sound allows clinicians to test patients’ spatial hearing in a clinic rather than in a laboratory setting. The apparatus adapts its tests to the ability of the patient – so it can be used for both children and adults, to participants with normal hearing, to users of acoustic hearing aids, and to users of the cochlear implants which are now provided to young deaf children.

Most importantly, the state-of-the-art software produces a report written in plain English, meaning clinicians no longer need to revert to the laboratory to interpret test results.

These implants have proven successful in helping young children to learn language – which is crucial so that they can attend mainstream schools

Professor Quentin Summerfield

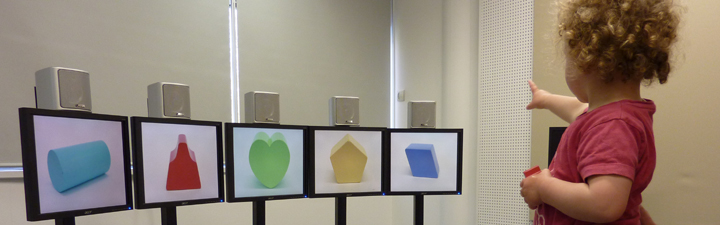

“One of the challenges of testing hearing in children so young is to keep their attention on the task,” explains Professor Quentin Summerfield, one of the lead researchers on the Crescent project. “To solve this problem, we added display screens to the system which present videos and three-dimensional images. These engage children’s attention and provide rewards when they respond accurately to the challenges presented by the system.”

The Crescent of Sound consists of a semi-circular arc of nine loudspeakers, seven of which have an associated computer-controlled video display. The speakers deliver sounds from different directions to measure the patient’s localisation skills, and can present speech from one direction together with noise from a different direction to create signals of different clarity at the two ears.

One of the main drivers for developing the Crescent has been a recent change in British healthcare policy. “Until recently, NHS guidance recommended that deaf children be given a single cochlear implant,” says Professor Summerfield.

“But these implants have proven so successful in helping young children to learn language – which is crucial so that children can attend mainstream schools, for instance – that newly updated guidance recommends two implants for each child, one in each ear.”

The research at York was commissioned by Advanced Bionics, a leading manufacturer of cochlear implants for hearing-impaired children. As well as maximising the impact of research by working directly with industry, the development of the Crescent and locating it in hospitals is now providing an infrastructure for further clinical research using Advanced Bionics’s implants.

Unlike acoustic hearing aids, which work simply by amplifying sound levels, cochlear implants actually bypass parts of the ear that are absent or damaged and instead stimulate the hearing nerve directly with electrical signals. Children who have been provided with two such implants, one in each ear, can essentially learn to ‘hear in three dimensions’ – so they know where to look to see who is talking, where to move to avoid hazards and how to understand what’s said to them in noisy environments such as schools.

This change in policy means that clinicians who provide implants to children must measure emerging skills in spatial listening in young deaf children. Until the Crescent was developed, such tests often had to be administered or interpreted in specialist laboratories, rather than in clinical settings.

Production versions of the Crescent of Sound are now being installed at the Royal National Throat Nose and Ear Hospital, the Bradford Royal Infirmary, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Crosshouse Hospital and St Thomas’ Hospital.

Further information