Patterns of Pilgrimage in England c.600-c.1100

Place Pilgrimage in the Anglo-Saxon Church

Introduction

St Jerome, eager to encourage friends to visit the 'holy' land of Palestine, claimed that 'the Briton ... no sooner makes progress in religion than he leaves the setting sun in search of a spot of which he knows only through Scripture and common report' (Jerome, Letters, XLVI). We cannot be certain how adventurous Christian Britons may have been but it is clear that Anglo-Saxon Christians showed a remarkable commitment to visiting the holy places of Christendom. Indeed in 889 the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle found it necessary to note: 'In this year no journey was made to Rome'.

Since the Anglo-Saxon Church owed its foundation to both Celtic and Roman missionaries, it is not surprising that it inherited a complex range of attitudes towards geographical or 'place' pilgrimage. Both the Celtic and Roman churches honoured the relics of saints and regarded particular places as holy because they were associated with particular people or events; both used pilgrimage as a form of penance. There were, however, also significant differences between them. Pilgrim-journeys therefore took three main forms during this period:

Strangers: 'Peregrinatio pro amore Dei'

The New Testament describes Christians as being 'strangers and pilgrims' on the earth, exiles en route to heaven. Like the Desert Fathers who retreated into the deserts of Egypt and Judea in the fourth century (see Early Christian Tradition), monks of the Celtic Church saw willingness to undertake literal exile, leaving family, home or homeland as a permanent act of renunciation, as having spiritual value in and of itself. It was peregrinatio pro amore Dei (pilgrimage for the love of God). Following the example of the people of Israel, who travelled through the wilderness towards the Promised Land (see Pilgrimage in the Bible) Celtic monks sought out their own 'desert' places in which to pray and do battle against the forces of evil. Sometimes these were on land, at other times they were islands - 'deserts in the ocean'. They demonstrated their willingness to journey with God into the unknown, as the patriarch Abraham had done, by literally placing themselves in small boats to be carried wherever the waves would take them.

Pilgrims: the cult of the saints

The Roman Church stressed the importance of journeying to specific places for specific reasons including learning more about the setting and content of the Bible or the life and worship of the Church, visiting the shrines of saints in search of healing or forgiveness for sin.

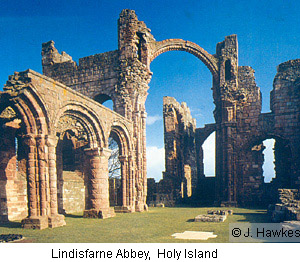

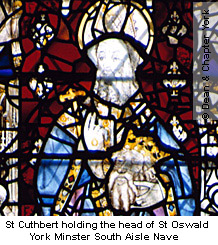

In addition to the saints' cults introduced from Rome, Anglo-Saxon England soon provided its own heroes and heroines of the faith. Over time shrines were established in honour of St Oswald, St Cuthbert (first at Lindisfarne and later at Durham), St Chad (Lastingham), St Aethelthryth (Ely), St Swithun (Winchester) and St Edmund (Bury). All drew pilgrims, seeking spiritual benefits and miracles of healing.

Anglo-Saxon pilgrims also travelled abroad. Within a century of the arrival of missionaries from Rome to convert the pagan Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon pilgrimage to Rome was already well established. Not only monks and nuns, but kings and other lay people travelled to Rome. Some, like King Ine of Wessex and King Coenred of Mercia, remained there to die close to the shrines of the apostles Peter and Paul; others, such as Benedict Biscop (d. 689) and St Wilfrid (d. 709), returned with relics, books and increased understanding of the history, teaching and liturgy of the Church. A hostel (schola) was established close to St Peter's for English pilgrims and other visitors to Rome. Women pilgrims also made the arduous and dangerous journey. In the mid-eighth century St Boniface (d. 751) wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury asking him to forbid 'matrons and nuns' to travel to Rome because many of them perished and few kept their virtue. Some English pilgrims travelled even further afield. St Willibald left an account of a visit to the Holy Land and Constantinople, recorded by an English nun, Huneberc or Hugeberc.

Exiles: the practice of penance

Although all pilgrimage was in some sense penitential, in that it was a response to a sense of sinfulness and the need to seek God's forgiveness, some voyages and journeys into exile were imposed on individuals by their communities as punishment for serious sin. Like Cain, the first murderer in the Bible, some were banished from their communities, either until they had fulfilled their sentence or permanently. In his Life of Columba, Adomnan tells of a murderer and oath-breaker who visited the saint, declaring that he had made the long journey in order to expiate his sins. A set of Irish Canons from a Worcester Collection (c.1000) states that the killing of a member of a bishop's entourage will incur a sentence of 'perpetual pilgrimage' or, at the least, a pilgrimage of thirty years.

Dee Dyas