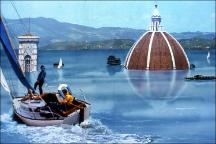

Art, Nature & the Environment in Italy

Overview

This trans-historical module explores the complex and shifting relationships between art, nature and the environment in Italy during the Renaissance (c.1350-1550) and throughout the twentieth century (c.1900-2000).

Although apparently so unconnected, there are deep similarities between twentieth-century attitudes to nature and the environment and those of late Medieval and Early Modern societies. This module draws from the intellectual approach of the visionary scholar Eugenio Battisti, who simultaneously looked back to the Renaissance at the same time responding to contemporary artistic trends, mutually informing his reading of both. The stark differences and strange echoes that emerge from this approach will help to illuminate the preoccupations of each period. Throughout, we will ask how aesthetic concerns have shaped definitions of nature and in turn how the material and social transformation of the landscape has informed artistic practice.

Art historians have long argued that landscape was of little interest to artists before the sixteenth century, but we will challenge this view and examine the ways in which concepts of nature, landscape and the elements permeated late medieval and renaissance texts, images, and architectural designs. We will consider the modern-day relevance of these past forms and debates as they have been contested in the twentieth century, exploring a rich and diverse tradition of artists who have engaged with Italy’s changing natural landscape throughout the twentieth century, integrating these concerns into a broader political discourse and drawing attention to the social conditions that shape the landscape.

Aims

By the end of the module students should have acquired the following:

- a critical understanding of the concept of ‘environment’ and its significance in art and culture in Italy

- knowledge of some of the main theoretical and historical approaches to the subject

- familiarity with a range of art works and the way in which the meanings of such works have been contested.

- the ability to look critically at a range of works made in a number of different media in relation to the themes discussed each week.

- high level skills in the visual analysis of works of art in the period under examination

- an ability to write critically and to develop a sophisticated written argument

- excellent verbal presentation skills and the ability to argue persuasively

The seminars of this jointly-taught module will explore a range of concepts and themes including:

- Biology as philosophy: thinking about nature with Lucretius and Piero di Cosimo

- Landscapes of sin and virtue: Paradise, Eden, and penitential deserts

- Otium: Escaping from the city: from Virgil to Radical Architecture

- Communing with nature: from Saint Francis to the hippies

- Personifying nature/ Anthropomorphic nature: from the Ancients to the new theorists

- The Nature-Artifice dichotomy

- Constructing, destroying and conserving nature: exploitation and productivity

- Mutability and cyclical patterns

Preliminary Reading

- Marco Armiero, Marcus Hall, Nature and History in Modern Italy (2010)

- Jay Appleton, The experience of landscape, Chichester, New York, Wiley 1996

- Veronica della Dora, Mountain: Nature and Culture, London, Reaktion Books, 2016

- Veronica della Dora, Landscape, Nature and the Sacred in Byzantium, CUP, 2016

- Ernst Gombrich, ‘The Renaissance Theory of Art and the Rise of Landscape’, Norm and Form, London 1966, pp. 107-21

- Wilko Graf von Hardenberg, Matthew Kelly, Claudia Leal, The Nature State: Rethinking the History of Conservation (2017)

- Tim Ingold, ‘The Temporality of the Landscape’, World Archaeology, 25 no. 2, October 1993, pp. 152-174

- Serenella Iovino, Ecocriticism and Italy: Ecology, resistance and Liberation (Bloomsbury, 2016)

- D Medina Lasansky, The Renaissance perfected: architecture, spectacle, and tourism in Fascist Italy (University Park, Penn.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004)

- Katharine Lochnan, Roald Nasgaard, and Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov ed., Mystical Landscapes: From Vincent Van Gogh to Emily Carr, Toronto: Prestel, 2016

- Mauro Lucco, Tiziano e la nascita del paesaggio moderno, Catalogue of exhibition in Milan Palazzo Reale 2012.

- Henry Martin, ‘Technological Arcadia’, Art and Artists, 2, 8 (1967), pp.22–5

- Filiberto Menna, ‘Una mise en scène per la natura’ [English text], Cartabianca, March (1968), pp.2–5. reprinted in Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Arte Povera (London: Phaidon, 1999), p.196

- W.J. Thomas Mitchell, Landscape and Power, University of Chicago Press, 2002

- Max Oelschlaeger, The Idea of Wilderness: From Prehistory to the Age of Ecology, New Haven: Yale U P, 1993

- Otto Pächt, ‘Early Italian Nature Studies and the Early Calendar Landscape’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 13, 1950, pp. 13-47

- K. Park and L. Daston, Wonders and the Order of Nature, c. 1150-1750

- Catharine Rossi, ‘From East to West and Back Again: Utopianism in Italian Radical Design’ in Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia, Andrew Blauvelt (ed.) (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2016), pp.58–67.

- James Sievert, The Origins of Nature Conservation in Italy (Bern and New York: Peter Lang, 2000)

- Hadas Steiner, ‘Life at the Threshold’, October, 136: 2011, pp.133–155

- Derk Jan Stobbelaar and Bas Pedroli, Perspectives on Landscape Identity: A Conceptual Challenge, 2011

- Simon Pugh ed., Reading Landscape: Country, City, Capital, Manchester University Press, 1990

- D.S. Wallace-Hadrill, The Greek Patristic View of Nature, Manchester University Press, 1968

- Mark Woods, Rethinking Wilderness, Peterborough, Canada: Broadview Press Ltd, 2017

- Christopher Wood, Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape, Reaktion Books, London, 1st ed. 1993, 2nd ed 2014

Module information

- Module title

Art, Nature & the Environment in Italy- Module number

HOA00090M- Convenors

Amanda Lillie and Teresa Kittler

For postgraduates

- Handbooks

- MA Modules 2023-2024

- Assessment

- Postgraduate funding

- PhD/MPhil supervision and training

- Resources

- Student activities