What's your greatest virtue? And what's your biggest vice?

Explore your best side - and your worst - in our exhibition at Hardwick Hall.

Perched high on a Derbyshire hillside, Hardwick Hall feels like a world apart. Yet the Hall, like its builder, Elizabeth Shrewsbury (better known as Bess of Hardwick), was caught up in the whirl of religious, political and cultural change that transformed Elizabethan and Jacobean England.

Visit the 'Virtue and Vice' exhibition to learn how England was shaped by the political, religious, and social upheaval known as the Reformation, and by encounters with new ideas, societies and beliefs. All of these threads twine together in the rich history of Hardwick Hall and the colourful life of its builder, Bess.

The exhibition was curated by Dr Helen Smith and the Conversion Narratives project team, in collaboration with staff and volunteers at Hardwick Hall. Find out about the inspiration for the exhibition, or discover the unique challenges of working in a remarkable Elizabethan house.

Image Gallery

Explore our illustrated introduction to some of the key themes of the exhibition.

Virtue and vice

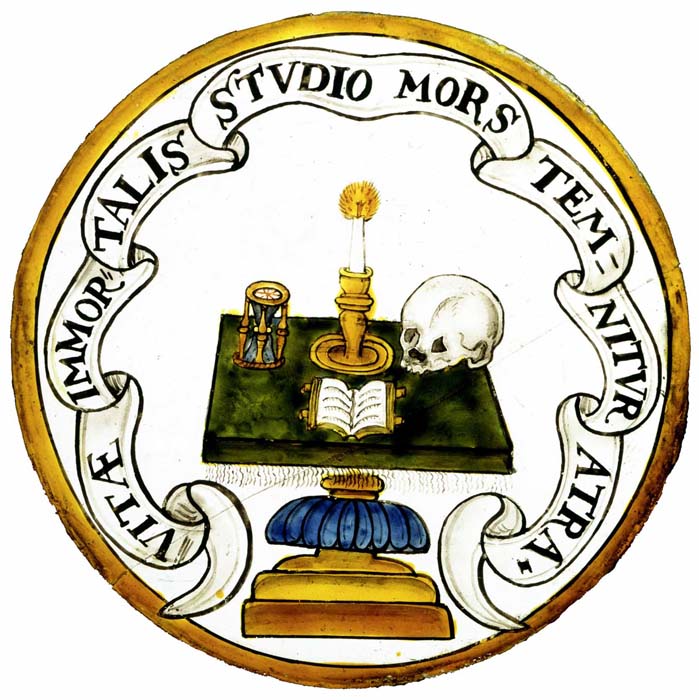

The exhibition picks up on a popular Elizabethan theme: the contrast between virtue and vice. We explore how ideals of virtue were used to proclaim and enforce cultural and personal values, and how stereotypes of vice and corruption attached to other faiths, nations, and practices. Drawing on the rich collections at Hardwick, we show how stories, objects, and actions came together in the pursuit of the good life - and the good death. And we reveal that the material histories of these objects - their own stories of making and use - are frequently at odds with the messages they are supposed to convey.

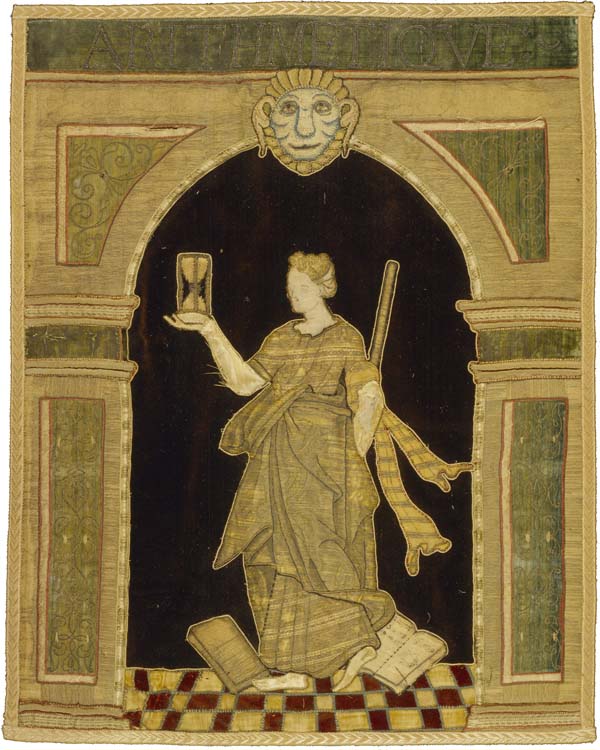

This hanging is one of three, comissioned by Bess and made by her household staff. They depict the theological virtues - faith, hope, and temperance - and their opposing vices. They are linked to hangings of the cardinal virtues - justice, prudence, fortitude, and temperance - now displayed on the Chapel Landing at Hardwick.

The tradition of personifying moral qualities stretches back to Ancient Greece and Rome. After the Reformation, the saints that featured in medieval images were replaced by Old Testament or classical figures. Bess's theological virtues are unusal in looking like elite Elizabethan women: Temperance looks suspiciously like Bess, and Faith bears a striking resemblance to Elizabeth I. Only a fragment of Hope and Judas remains.

In the middle ages, Faith was contrasted with idolatry or with the Egyptian priest and arch-heretic Arius. By the Renaissance, the military might of the Ottoman Empire meant that Islam was seen as the greatest threat to the Christian faith. Rumours and stereotypes about Islam and the East circulated widely. In the seventeenth-century, it was even believed that drinking coffee might change your religion!

This is not the only fabric representation of this theme: the tapestry series known as Los Honores (The Honours) was woven for Charles of Habsburg when he became Holy Roman Emperor in 1519. In that version, Faith crushes the figure of Mahomet underfoot. In the Hardwick hanging, rather than crushing Mahomet, Faith offers him the cup of true religion, reflecting English fantasies that the trading treaty Elizabeth signed with Sultan Murad III in 1580 might lead to the conversion of 'the Turk'.

In 1588, the writer Anthony Munday translated a French romance in which the hero, exploring a city under Turkish rule, enters a hall 'hanged round about with rich Tapistrie, wherein, the Historie of great Mahomet was curiously wrought'. This intriguing description suggests both French and English readers were aware of Muslim textile traditions which celebrated the prophet.

A sixteenth-century flash mob

See what happened when we took 'Les Canards Chantants' to Hardwick Hall to celebrate the launch of our exhibition...

The group are singing from the famous Eglantine table, which features inlaid wooden sheet music. The song, 'Lamentation' was first printed at the end of the 1562 edition of The whole booke of Psalms, translated into English verse by Thomas Sternhold and John Hopkins. According to the book's authors, psalms and devotional songs were 'very mete to be used of all sortes of people privately for their solace & comfort, laying apart all ungodly songes and ballades, which tende only to the nourishing of vyce, and corrupting of youth'.

Download our app

We've created an app for mobile and handheld devices to accompany the exhibition. Use the app to navigate Hardwick when you visit, explore the exhibition themes before you arrive, or revisit favourite objects and moments from the comfort of your own home. There's even an estate walk, if you're feeling adventurous! Download the app for Android or iOS devices. If you enjoy the app please do rate it, and share your feedback with us!