Behavioural Profiling: Making Player Data Actionable

Contact: Professor Anders Drachen

In modern game development, it is crucial that we can place our players into sets of groups, where everyone in those groups shares specific traits. Without being able to do this, our ability to understand who the players are, and how they play our games, is hampered. The ability to profile the players is important because different groups of players react differently to the same stimulus and behave differently within the confines of the same game. We need to understand these differences so we can deliver the best possible user experience to the players.

“When faced with overwhelming data about users, adopt the standpoint of condensing the data into a format where they are useful to you. Profiling is one such tool. This requires identifying the right data to work with and sacrificing detail but can be a great way to enable taking action on user behaviour.” (Drachen, 2016)

Going back a decade or more, we relied on basic segmentation as the way to try and get a handle on the diversity of player behaviours. Essentially, we would divide the user base into groups of individuals that were similar in specific ways. The player traits we looked at would be informed by the stakeholder requesting the analysis, rather than informed by the behavioural data that might be available.

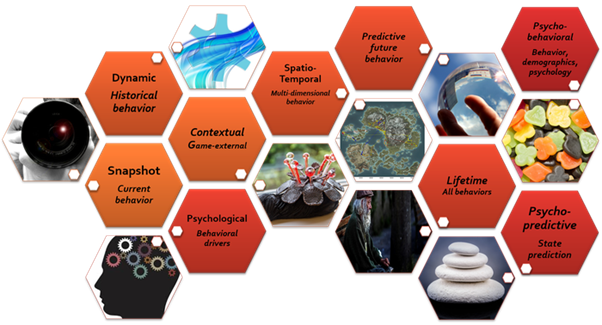

Since we introduced telemetry systems in our games, we have been able to create more accurate descriptions by investigating behaviour, usage, and habits of a population in a game. However, to a large degree, the segmentation of players is still based on aggregate information. For example, player X has killed Y opponents. Alternatively, we use average values across the whole population of players. Such numbers are from the perspective of the designers of contemporary major commercial titles almost meaningless. These statistics become actionable only if they are delivered for a specific group. For example, it could be expected that a population of risk-taking players have a high death rate. If the same happens to conservative players, it can be symptomatic of imbalances in the game. Behavioural profiling has been introduced in recent years as a means for building more accurate and actionable groups of players.

There is currently a wealth of different models being employed across academia and industry. Unfortunately, very few of these are productized to a significant degree.

Furthermore, a lot of the profiling work out there still works with aggregate data and capture only snapshots of the player behaviour. These are not always useful to design teams, but rather useful for informing strategic business decisions. While much more complex and information-rich profiling techniques exist, which include for example psychological information about the players, these are much less integrated in the industry and much less investigated in academia. That being said, behavioural profiling is attractive as a means for building a better understanding of our players and how to find out what they are interested in. This because these techniques allow us to consider them in a quantifiable way, using telemetry data.

Today, major commercial titles can track hundreds if not thousands of behavioural metrics from each player, on a continual basis as they progress in a title. Given the raw variance space such telemetry data create, we need tools to condense these behaviours into formats that showcase the patterns in the data. We also need tools that refine these patterns into a format where we can utilize them.