Bauhaus and Weimar Culture

Overview

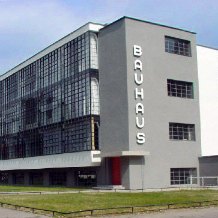

The Bauhaus is the most famous design school of the modern era based on modernist aesthetics and a dramatic reform of art education. Although it only had a limited lifespan from 1919 to 1933, its influence on the look of the modern world has been enormous.

The concept of a basic or foundation course developed there is now the staple of art education in many countries worldwide. While Bauhaus design is now familiar to us (as Tom Wolfe suggested in the title of his book, From Bauhaus to our House), the context that gave rise to the institution is now quite remote. Founded in the aftermath of the First World War in a country on its knees economically, the school dedicated to building (Bauen) was unable to put up a single structure for the first half of its existence. Forced to leave its first home in Weimar in 1924, the school moved to Dessau until forcibly closed again in 1932 and finally shut down by the Nazis at its last site in Berlin in 1933. That so much could have been achieved in its brief existence, lurching from one crisis to the next, is testimony to the strength of the utopian aspirations that drove it.

This module aims to explore the Bauhaus from a range of perspectives to unravel its legacy by looking at its interaction with contemporary art, industry, popular culture and politics. The question to be posed is how the Bauhaus could accommodate the esoteric abstract paintings of Wassily Kandinsky with the mass-produced furniture of Marcel Breuer or the Bauhaus jazz band with the austerity of prefabricated housing. To answer this question we will try to understand the culture of the inter-war period in Germany as a whole, looking at themes such as responses to the war, modernism and mass culture, design and mass production, film and photography, and architecture and urbanism. As well as Kandinsky and Breuer, some of the major figures included may include Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Walter Gropius, Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, Johannes Itten, Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Preliminary Reading

- Anja Baumhoff, The Gendered World of the Bauhaus (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2001)

- Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickerman eds., Bauhaus, 1919-1933: Workshops for Modernity (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2009)

- Magdalena Droste, Bauhaus 1919-1933 (Cologne & London: Taschen, 1998)

- Eva Forgács, The Bauhaus Idea and Bauhaus Politics (Budapest and London: Central European University Press, 1995)

- Eleanor Hight, Picturing Modernism: Moholy-Nagy and Photography in Weimar Germany (Cambridge MA: MIT, 1995)

- Elaine Hochman, Architects of Fortune: Mies van der Rohe and the Third Reich (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1989)

- Kathleen James-Chakraborty ed., Bauhaus Culture: From Weimar to the Cold War (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006)

- Jeffrey Saletnik and Robin Schuldenfrei, Bauhaus Construct: Fashioning Identity, Discourse and Modernism (London & New York: Routledge, 2009)

- Rainer Wick, Teaching at the Bauhaus (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2000)

Module information

- Module title

Bauhaus and Weimar Culture- Module number

HOA00029M- Convenor

Michael White

For postgraduates