Chemist on Kirkgate

Posted on 8 June 2015

Sabine Waasdorp

Visiting student, 2014/5

In my placement, I worked together with the York Castle Museum and descendants of the chemist John Saville (1834-1926). The replica of John Saville & Sons pharmacy on Kirkgate, originally located on Goodramgate No. 4, needed a bit of attention. Although the pharmacy itself is a popular location for the visitors – its popularity mainly caused by the beautiful interior of the pharmacy with the mysterious medicine glass jars at the back of the store – the information provided was too impersonal. The guides, dressed in Victorian clothing, usually talked about general medicine in the nineteenth century (the use of poison, leeches, the art of physiognomy and the differences between doctors, chemists and apothecaries). Stories about John Saville and his patients were, however, missing.

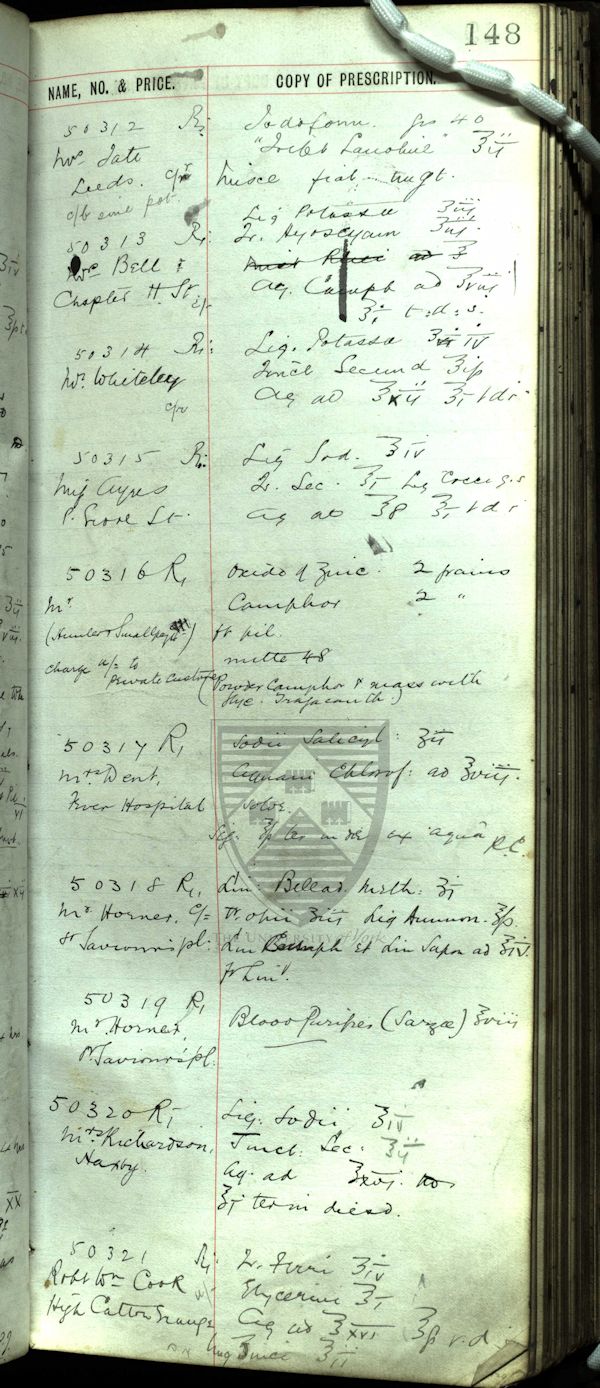

Luckily, there was personal information available, in the shape of eleven prescription books covering the years of 1895 to 1901. These books, in the care of the Borthwick Institute for Archives, hold the information of all Saville’s patients, coming from the lower and higher classes of York and its surroundings. The York Castle Museum, and the Saville family itself, who are heavily involved with the pharmacy on Kirkgate, had asked me to research these prescriptions books and add a social layer to the current exhibition of the pharmacy.

This request proved to be a huge and difficult task, especially for a student of Dutch early modern literature who isn’t familiar with the English medical world of the late nineteenth century. The material itself was first of all very extensive: each book contained between 3,000 and 10,000 entries, all written in a sometimes very scribbly hand. I therefore chose to focus on one book, Volume 7 (1895-1901) and on the families which came back the most for a prescription. After this selection, the real ‘trouble’ started: all prescriptions were written in Latin and were abbreviated! So what did ‘Syr. Zingiberis’ (Syrup of Ginger), ‘Mist Diarr Fort’ (Strong Diarrhoea Mixture) or ‘Aq Camph’ (Camphor Water) mean? With the help of nineteenth century medical dictionaries, Google and some information in the York Castle Museum, I could figure out most of the prescriptions, but some of remained a mystery.

In the end, I created an encyclopaedia. This contained each abbreviation I encountered, with its English equivalent and a short entry with all the properties of that specific ingredient. The encyclopaedia can be used by the intern next year, for whom the prescriptions books hopefully won’t be such a puzzle as they were for me at the start. I also wrote short narratives, based on the medical histories of the families I focused on, which will be used by the guides. These stories will hopefully make the pharmacy a lot more real and lively!

I truly enjoyed this experience. The York Castle Museum staff were very friendly and were always enthusiastic about my ideas. I had the chance to look in the catalogue of the museum and help choose new items for the exhibition, as well as spending a day in the pharmacy to investigate all the items it had in store. Truly significant was the fact that I spoke on BBC Radio York about my project. This short moment of fame has made this internship one of the great projects I conducted in my brief time in York.

Image acknowledgements

Permission to reproduce documents in the custody of the Borthwick Institute has been granted (YMS 5, Volume 7. John Saville prescription books. Page 148.)