Harewood West Indian Archive

Browse the Harewood West Indian Archive

About the Project

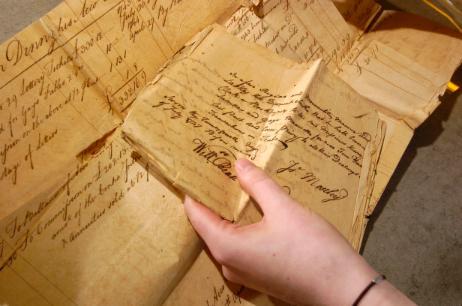

In summer 2005 we took delivery of seven boxes of archives relating to the activities of the Lascelles family in the West Indies, dating from between 1677 and the 19th century. The collection had originally been held at Harewood House, West Yorkshire, the home of the Lascelles family, and was transferred to us from the Harewood House Trust. The archive documents the Lascelles’ ownership of plantations and enslaved people in the Caribbean in the 18th and early 19th centuries. It also documents the first years of the apprenticeship systems which replaced enslavement in British colonies in 1834. A project to conserve and box list the archive, which ran from 2005 to 2007, was carried out with funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund (now National Lottery Heritage Fund).

The archive appears to be a part of the business archive of Lascelles and Maxwell, the London commission house through which much of the Lascelles business was conducted. Most of the documents in the archive relate to business transactions - foreclosures on mortgages, acquisitions of property - and supporting papers associated with these activities. These supporting papers include wills, bonds, orders for the sale of enslaved people as a result of the debt or bankruptcy of the owners, and correspondence from debtors begging for more time to pay a debt, or advancing reasons why their debts should be treated more leniently than the law would suggest (for example in the case of widowhood). There are also accounts detailing expenditure on other associated business activities, including the shipping of sugar and other cargoes, and the running of plantations. Unfortunately, whilst documents do survive naming particular enslaved people, there are no records of their voices or individual stories within the collection.

There is also a significant number of documents in the collection relating to the Yorkshire parliamentary election of 1807, including many printed election posters, some designs for banners, and manuscript versions of scurrilous or satirical verses used as part of the campaign. The campaign has been extensively studied, see, for example The British Slave Trade: Abolition, Parliament and People edited by Stephen Farrell, Melanie Unwin and James Walvin (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press for The Parliamentary History Yearbook Trust, c.2007).

Some of the documents in the archive were created in London, and others in the Caribbean; obvious differences between them are the use of paper for deeds, when the normal English practice was to use parchment.

In 2017, we added to the existing collection when we received a further five boxes of related archives from the Harewood House Trust, which had previously been held at West Yorkshire Archives Service in Leeds. These archives cover the period 1745 to 1891, and are now included in the same list as the original material received in 2005.

In 2023, we added images of the documents we received in 2005 to JSTOR Open Community Collections. The images can either be browsed directly on the JSTOR website, or you can find links to relevant digital images in the individual entries on our online catalogue, Borthcat.

The Lascelles Family and the Caribbean

The Lascelles family, now earls of Harewood, had interests in the Caribbean from 1648 until 1975, when the family sold its last plantation. The fullest account of their activities is Simon Smith's study Slavery, family and gentry capitalism in the British Atlantic: the world of the Lascelles, 1648-1834 (Cambridge Studies in Economic History, Cambridge University Press 2006).

The information in this section is heavily reliant on Smith's work for much of the information it contains about the Lascelles' activities.

Smith hypothesises that

... a new framework for business association was established by mercantile communities based in London, Barbados, and North America between the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries ... a key element of this framework lay in the control of complex credit networks, crucial for the success (or failure) of Atlantic commercial ventures. Merchant's strategies were shaped by the working of the credit market, ultimately obliging the Lascelles to become large-scale plantation owners ... by the mid-eighteenth century Caribbean colonies and transatlantic trade were subject to fiscal-military control through the medium of naval power and metropolitan credit ... the instruments of control [were located] in gentry capitalist networks of kinship and regional affiliation, matrimonial alliance, mercantile expertise, and public service.

The key members of the family were the three sons of Daniel Lascelles. The eldest, George, is known to have been in Bridgetown, Barbados before 1706. Henry joined him in 1711 or 1712 and their brother Edward (by Daniel's second wife, Mary) travelled to Bridgetown in 1715 (at which point George departed to handle the family's business at the London end).

Sugar was the main reason for their being there, and their initial activities were as sugar merchants. Enslavement and the use of enslaved people in the production of sugar was an early interest, post-dating Henry Lascelles' marriage to Mary Carter, daughter of a Barbadian slave trader. Henry's first documented involvement in the trade came in 1713, when he and two fellow traders shipped 100 enslaved people from Barbados on the Carracoe Merchant. The remaining foundation stone of the family's fortunes in the Caribbean was laid in 1714 or 1715, when Henry became Collector of Customs for the port of Bridgetown. Edward succeeded him in this position around 1730. The post was lucrative in its own right, and provided further opportunities for raising additional capital, which led to allegations of corruption and his temporary suspension from the post.

Success in trading, and the revenues resulting from the customs post, allowed the Lascelles to build up sufficient capital to be able to lend money. Between 1723 and 1753 Henry (in London) lent £226,772, of which £95,000 was in the form of mortgages, the vast majority of the latter being dated between 1730-1734 and 1745-1753. The significance of this activity lies not only in the return on capital that successful repayment of mortgages envisaged, but also in the failure to repay; for failure meant foreclosure, and the transfer of the mortgaged property to Henry. Much of the surviving documentation in the archive relates to money lending and mortgaging and their consequences.

Once a plantation owner defaulted on a mortgage, then the plantation, with all chattels belonging to it - including the enslaved people - became the property of those who had advanced the mortgage loan. This was the major mechanism by which the Lascelles became plantation owners, together with attendant enslaved workers. As Smith points out, however, this activity was not primarily devised as a way to acquire plantations. Although Henry and Edward Lascelles acquired some plantations during the course of their intricate business transactions, all these were sold when they died, leaving the family with no land holdings in the Caribbean in 1759. Harewood House was actually planned in 1759 and completed for occupation in 1771, but neither Edwin nor Daniel Lascelles had any land or enslaved people in the West Indies by the time of its completion.

The acquisition of estates began in 1773 - by 1787 the family held more than 27,000 acres in Barbados, Jamaica, Grenada and Tobago. In changing their strategy the family were responding to changed economic and political conditions, brought about by a credit crisis in the Caribbean in 1772-1773 and the American Revolutionary War between 1776 and 1783.

Having become owners of plantations and enslaved workers, the Lascelles continued to protect their rights over their human property, firstly from those who wanted to abolish the trade in enslaved people (who succeeded in 1807) and secondly from those who wanted to abolish slavery itself (who succeeded in 1833). The family did not sell their final plantation in the Caribbean until 1975.

Further Information

Information on the 2005 project, the archive and the conservation techniques employed can be found in Conserving and Making Available the Records of Slavery: Harewood House (.pdf file)

All of the documents in this collection are available to research in our searchroom. We advise making appointments in advance, and more information about visiting us can be found on our website: https://www.york.ac.uk/borthwick/visiting-us/. You can also view our online digital images of parts of the collection at JSTOR Open Community Collections, and through the links in the individual entries on our online catalogue Borthcat.

Please be aware that parts of this collection contain distressing material and language that is offensive or harmful. Please see our harmful language statement for information as to why such language may appear and learn more about work we are undertaking to remediate oppressive language. This statement will also appear in the catalogue entries concerned, in the Scope and Content field. If you have concerns about language used in the records, please contact us at borthwick-institute@york.ac.uk.

Acknowledgements

The images showing documents under conservation on this web page were taken by Bruce Rollinson of the Yorkshire Post.