Meet your tutors

Congratulations on your offer! If you join us, you’ll learn from academics with expertise in a whole world of interconnected literary cultures. Your modules will cover a huge range of periods, regions, languages and disciplines.

George Younge is one of our many inspiring staff members. His expertise is in the transition from Old English to Middle English, after the Norman invasion.

Contact us

For any support or guidance on completing your journey to York, we're always close at hand.

It was curiosity, really

I grew up in Norfolk, and there are deep layers of history there. It was one of the most densely populated parts of the country in the medieval period. You walk around now, and you see churches and ruined monasteries, and you think, ‘why has no one ever studied that?’

I completely failed when I was an A level student. I had no promise whatsoever. And then I just became interested. To go from that, to university, to doing a PhD at Cambridge, to lecturing in one of the top universities in the country - I’m pretty proud of turning it around.

There was literally a gap in the bookshelf

At university, I worked on Anglo-Saxon literature. In the library there was a series of books from the Early English Text Society. They covered Old English, which is the earliest form of the written language, and Middle English, which is a bit more like everyday speech.

I wanted to know what came in between. How did the very earliest form of English - the bit that we share with the Germanic and Scandinavian countries - morph into the language that we know today?

Everyone thought that Old English stopped in 1066

That was the common consensus: the French-speaking invaders stamped out the English language. My PhD thesis pushed against that idea. I looked at the books that were written in the century after William the Conqueror came, and lots were written in English.

I showed that English was in quite common use, and not just by a small group trying to resist French cultural dominance. In fact, French speakers who came over were very interested in English, and it inspired the Normans to write in their own language.

King's Manor Library

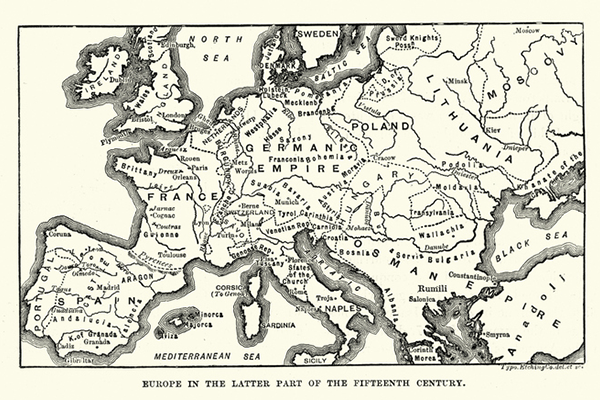

A map of Europe in the latter part of the 15th Century

It’s a common pattern across Europe

Conquests and colonisation lead to languages coming into contact, then inspiring each other or creating new fusions, and new forms of literature. At York, we’re very interested in this idea. English doesn’t exist in a vacuum: languages have to have influences.

The debate surrounding Brexit has been electric. Are we local? Are we regional? Are we national? Are we international? It’s all channelled through literary studies.

We're incredibly international, but English literature has historically been a touchstone for English national identity. It puts you right in the epicentre of a debate about what our place in the world is.

The first year can be a bit of a shock

I mean that in a good way. You’ll suddenly encounter all these new dimensions of literature and literary study. Our 'A World of Literature' modules open up cutting-edge questions about the development of English Literature and its place in the world. 'Approaches to Literature' gives you the skills you need to get to grips with literature, right through from the Medieval and Renaissance periods to the present. There are so many different regions and literary approaches we study - it really sets York apart.

For example, we’ve recently been joined by Dr Shazia Jagot, who’s working on Medieval Arabic. So, we’ve got coverage of the Middle East and Byzantium, China, African and South African literature - it’s so diverse. I think that’s pretty unique.