From food history and 'hippocras' to early modern Christmas at Fairfax House

Posted on 23 December 2021

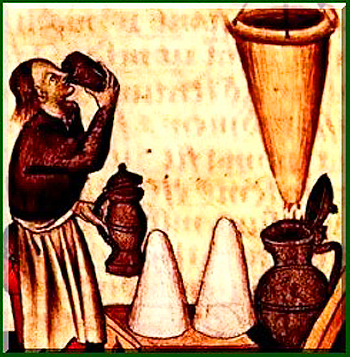

Hippocrates's sleeve being used to make hippocras wine

Tabitha Kaye, BA English Literature and History 2019-2022

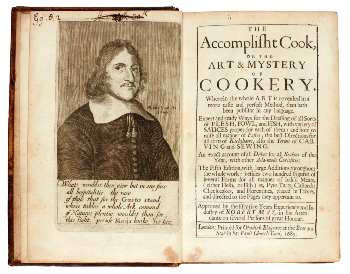

In the penultimate week of our autumn term module, Objects and Ownership in Early Modern England, our seminar took an interesting turn. Armed with an extract from Robert May’s 1660 guide, The Art and Mystery of Cooking, we were tasked with recreating a popular spiced wine: hippocras - or ‘Ipocras Otherwayes’ as it appeared in the recipe. May’s guidance was sparse and relied upon common culinary knowledge (something us students are infamously lacking), so we could only speculate as to what the method truly entailed. Nevertheless, we surveyed the extravagant amount of sugar and spices before us and came to a unanimous conclusion: hippocras must be a festive tipple akin to mulled wine.

We were, of course, far from correct: generally, hippocras was used for medicinal purposes all-year round. Regardless, we had emerged on the other side with a few interesting questions (if not a bottle of non-alcoholic wine textured by two pounds of un-dissolved sugar). The first of which was the issue of whose history we were engaging with. In jumping to the conclusion that hippocras was a Christmas treat, our first thought of an early modern Christmas was luxury and splendour based upon the ability to consume sugar and expensive spices. Although, while May’s recipe would have set the average skilled labourer back a few days wages in 1660, the consumption and production of hippocras was not exclusive to wealthy households. Thus, the question of luxury intrigued me: was this just a case of imposing modern understanding of Christmas - spiced flavours and indulgence - onto a seventeenth-century recipe, or was there something to be said about how the history of Christmas was represented and reinforced in the public domain?

A raucous Georgian Christmas dinner party showcasing the magnificent collection of Georgian silverware donated by Arthur Smallwood. Credit: Fairfax House, York.

Naturally, Fairfax House was my first thought: York’s very own archetype of Georgian grandeur. At the time of our seminar, festivities in York were in full swing and two rooms in the house had been dressed beautifully in lavish eighteenth-century inspired decorations. This year, the stars of the show were two curator-led ‘Candlelit Tours’ as part of their A Season of Giving. The augmentation of the candle light set the stage for an ‘authentic’ and immersive experience. From the feedback, the latter was highlighted frequently, with visitors commenting on how the lack of artificial lighting ‘brought the house to life’. The exclusivity of the tours guaranteed that demand for this year did not wane. However, I couldn’t help but speculate as to whether the toll of COVID-19 restrictions had helped increase interest. After the uncertainty and social constraints of the past year, an eighteenth-century, upper-class Christmas punctuated by a busy social calendar and hearty dining was the perfect place for visitors to take refuge and find comfort.

Robert May, The Accomplisht Cook, or The Art & Mystery of Cookery, 1685. Credit: Sotheby's.

The positive response to Fairfax House’s display inspired me to write a Christmas article for the 'Food and Drink' section of the University of York's student-run newspaper, Nouse. I loved the idea of an immersive experience and attempted to create a guide to an early modern Christmas so that readers could attempt to ‘perform’ history from the comfort of their own home. My impulse was to make the article as historically accurate as possible in terms of recipes - something that was easily achievable with a wealth of sources akin to May's guidebook, such as the works of Hannah Woolley. However, we had enjoyed our hippocras-making session so much that I was keen not to lose an element of fun. This worked particularly well for our broad target readership as the content had to strike a balance between recognisable ‘festive’ tastes for a modern palette and offering some insight into what would have realistically appeared at a 'Twelfth Night' feast. As such, my structure tended towards introducing a source, such as Woolley’s minc’d pies, and suggesting a ‘modern’ twist - even if this twist was the less exciting fact that such pies had little association with past Christmas celebrations. In addition to a plum pudding dessert, I even suggested heating up some chocolate sponge by the fire to encapsulate the spirit of lighting the yule log - I’ll admit that this one was a bit far-fetched, but perfectly matched the cosy nature of the article.

Georgian glassware gifted by John Butler, part of a 400-piece collection to be displayed in the Saloon. Credit: Fairfax House, York.

In writing this article, it dawned upon me that I had manipulated history in a manner that reinforced our perceived connection between the history of Christmas and luxury. Even in the case of wassailing I had prioritised recipes which conjured a warm and secure image of Christmas. Alternatively, I could have considered recipes which reflected the importance of community rather than higher class gatherings, as re-creating a middling-class Christmas would have encapsulated festive cheer in this sense. However, I doubt a guide on re-creating a pauper’s Christmas (aside from the fact that sources would be hard to find in terms of food content) would have featured the creature comforts we are searching for in 2021.

In terms of Fairfax House, the building has a duty to be faithful to the narrative of the Fairfax family and, subsequently, how the northern gentry would have celebrated the festive season. Visitors typically approach the museum with this knowledge, but I wonder to what extent this is overshadowed, if at all, by this expectation of splendour, and how much they are prepared to negotiate these preconceptions. Along these lines, I would love to see how an immersive experience of a lower class or pauper eighteenth-century Christmas would be received. Granted, a place such as the York Dungeons attraction wouldn’t radiate the same warmth as Fairfax House, but the promise of a hearty glass of hippocras afterwards - provided our seminar group has no hand in making it - may just seal the deal.

Fairfax House's 2021/22 A Season for Giving runs from 20th November to 9th January.

The admission charge is £7.50 (children under 16 go free).

Walk-ins are available throughout the day, and pre-booking is also available: https://fairfax-house.arttickets.org.uk

For any booking queries, please call 01904 655543 or email events@fairfaxhouse.co.uk

For a full list of our safety measures in place, visit: http://www.fairfaxhouse.co.uk/visit/visit-safely-with-us/

General access information can be found here: http://www.fairfaxhouse.co.uk/visit/access/

Follow Tabitha on Twitter @tab_kaye