Performing Lola Montez

Posted on 15 December 2022

Esther Wilson as Lola Montez (right), Emily Brighty as Mary Isabella Gascoigne (left) (credit: Stephanie Davies, Community Curator, Lotherton Hall, Leeds Museums & Galleries Trust)

Esther Wilson, WRoCAH-funded PhD student, History department

I had known Community Curator Stephanie Davies for a few months when she approached me about getting involved in her upcoming community project, ‘The Homes of the Gascoignes’. Based at Lotherton Hall (Aberford, Leeds), the exhibition is designed to showcase the country estates owned by the Gascoigne family, who presented the Lotherton estate to the city of Leeds in 1968. The exhibition not only aimed to broaden visitors’ understandings of the Gascoigne family and their ancestry, but sought to use community volunteers in order to share the stories of the ‘real people’ behind the grand facades of Parlington, Castle Oliver and Craignish. This is where I came into Stephanie’s schemes.

Lola Montez, born Eliza Roseanna Gilbert, is most well known for her reputation as a 19th Century international dancer and courtesan. Her escapades of mysterious missing men, evocative dances and involvement in European revolution are the key legacies left behind within public general knowledge. Lesser known is that this dazzling ‘Spanish dancer’ was actually a young Irish gentlewoman from the estate of Castle Oliver in County Limerick, Ireland, who would finish her life a penniless charity worker and penitent protestant. Her life story itself is somewhat astounding; Montez was ousted by polite society, never went to Spain and never took ballet training, but managed to tour the stages of the world, become Ludwig I of Bavaria’s revolutionary Countess of Landsfeld and develop an international voice in women’s etiquette and toilette. My task, as a public history researcher and dancer, was to tell these stories and, I personally hoped, change some perceptions as part of a 2-hour heritage event which ran in October 2022.

The afternoon had several components – an exhibition tour featuring my interpretation of Lola’s infamous ‘Spider Dance,’ an afternoon tea and a workshop on 19th-Century health and wellbeing led by myself. I was supported in these by friend and fellow volunteer Emily Brighty who played Montez’ ‘cousin’ Mary Isabella, though as Emily took the mantle of the exhibition tour, the rest became largely my responsibility. I had few immediate qualms about the workshop component – I have experience in working in heritage settings and an interest in 19th-Century history, Lola’s own publication The Art of Beauty was on-hand and my experience in teaching adult ballet classes made the ‘activity’ component (teaching visitors a few bars of ‘Spider Dance’ choreography) fairly natural. The rest of the afternoon, however, felt less certain. Various challenges quickly presented themselves; not only was I bursting onto the acting scene as a real historical individual, but in creating an event which aimed to effectively communicate the past to an unknown visiting public, I had to negotiate between my largely non-performative previous heritage industry experience and my normative academic forms of research and communication. I would need to identify and call into question any personal assumptions of how to do heritage in practice. The task of character development and script-writing posed big questions about how to appropriately develop a sense of historic persona and navigate notions of authenticity within the context of the required work. Importantly, I also had to face up to the ‘Spider Dance’ itself; how was I to re-create a historic dance with minimal and conflicting source material and just how does one communicate ideas about the past through dance, anyway?

One thing that was generally made easy for me was the costuming. Fantastically designed and created by Northern Ballet costumier Julia Anderson, the costume was designed to echo the attire worn by Lola in a contemporary portrait currently held in the New York Public Library collections. I say costume, but the garment really teased the line between understanding of ‘dress’ and ‘costume’. With extensive experience in creating costumes which evoked a sense of period feel, Julia recreated the 1840’s silhouette beautifully without the requirement of corseted underpinnings, while retaining the practicality required for movement in the costume. Having worn various forms of authentic 1840’s daywear as an ‘extra’ for film and television, I marvelled at the way the dress made me feel as a performer and a character, particularly in contrast to the restrictions of the formal corsetry and various volumes of petticoats that I’ve worn on film sets. It would have been wonderful to have known just how Lola herself negotiated the balance of appearance, costume, theatrics and movement.

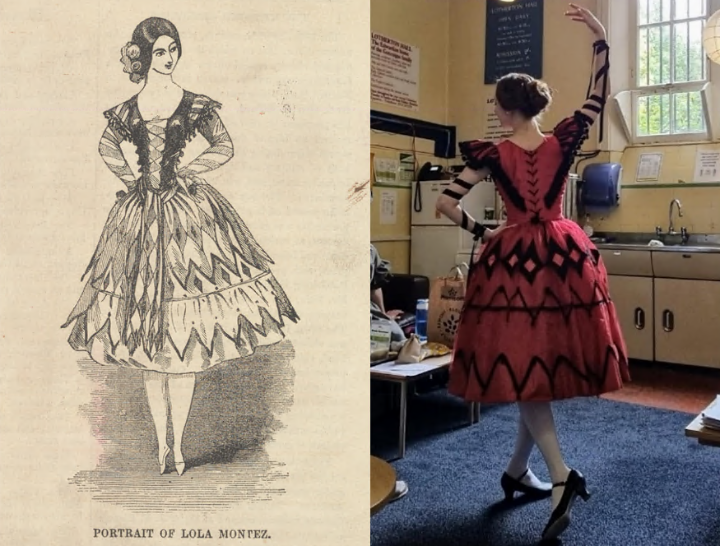

Portrait of Lola Montez (New York Public Library) (left) and Esther Wilson as Lola Montez (credit: Stephanie Davies) (right).

One wardrobe decision that I did make myself was a last-minute opt towards ‘character shoes’ for the performance. You can see these on the picture on the right, rather than the sort of slippers depicted within the portrait. This decision was partly centred around practicality, but has also encouraged me to think more critically about ‘authenticity’. We don’t know exactly what Lola wore for her performances of the ‘Spider Dance’ when it debuted. The shoes depicted in the portrait on the left may or may not have been representative of that particular performance costume, but they also don’t accurately represent any shoes from the 19th-century that I would be able to recreate today. They depict Lola as being ‘en-pointe’. Aesthetically, the portrait fits with many early to mid-19th Century dancer images, a fitting decision given the wild recent success of romantic ballets such as Giselle and La Sylphide, which had begun to use early forms of what we now understand as ‘pointe work’. However, modern pointe shoes are extremely different to their predecessors of 200 years ago, having adapted into supportive and more practical shoes which enable ever-more challenging choreographic demands. It would therefore be impossible for me to imitate this look with one of my 21st-Century pairs. We also don’t believe that Lola had access to ballet training, or was seen as sufficiently capable if she did. Given the strength and technique required (particularly without the more robust, modern shoes), I think it’s highly unlikely that Lola ever danced en-pointe. Although the portrait was used for costume inspiration, the footwear shown is thus highly likely to be inaccurate or misrepresentative - perhaps comparable to depictions of ballet dancers at the time, but probably not to Montez’ shoes.

Cost restraints aside, this means that the likeliness of my ability to replicate appropriate, authentic 19th-Century dance slippers of any style was minimal. Inspired to some extent by the portrait, the initial pair of modern ‘flat’ white ballet slippers chosen felt too out of place with their crossed elastic and form-fitting shape. Anachronistically clashing with the historical style of the rest of my appearance, they didn’t ‘feel’ the best option. However, as Lola was known to style herself as the ‘Spanish Dancer,’ I took artistic licence and chose to wear my ‘character shoes,’ worn by myself for ‘The Spanish Dance’ from The Nutcracker, a ballet which is generally understood to be set in early 19th-Century Germany. The character shoes, with their low heel and striking black appearance in contrast to the white tights, are also not particularly fitting for the 1840’s in terms of accurate historical footwear. However, as the performer and public historian in charge of the choice, it surprisingly felt that I’d made the right decision to rely upon period hair and dress silhouette as the key indicators of period, and that somehow, the shoes could add to this in their own way.

In spite of the inauthenticity, the appearance and action of the shoes within the piece seemed to function well as an indicator of ‘tone’ within the dance. Afterall, the imagery that could be conjured in the minds of 21st-Century visitors by Lola’s portrait as a type of ballet dancer is rather at odds with the sort of movements and attitude reportedly involved in the ‘Spider Dance.’ On the other hand, the character shoes seemed to facilitate a more accessible, contemporary performance tone which could be subtly sexualised while retaining practicality and acceptability within a 21st-Century dance context. Although I willingly opened the can of worms of historical authenticity, I do defend my position to have settled on footwear which better matched the performance context of the piece and hope for opportunities for future research into these sorts of problematic conversations. We cannot always represent the past literally and indeed it is not always quite what we want to do; instead, we want to translate and tell these stories in a way that makes sense to the modern audience. Sometimes, this seems to require compromises.

Creating the dance itself was perhaps the biggest key challenge. Fellow volunteers were excited to see the choreography unfold, supposedly as scandalous as her reputation, and no doubt this is what any other visitors may have expected also. The piece was reportedly debuted in Australia to conflicting levels of public reception; on the one hand an audience hurling golden nuggets, and on the other shock and appal at the evocative sexual performance and the revealing of public nudity. It’s difficult to know quite what the dance consisted of, but is so-called for Lola’s skirt-swishing movements, as if shaking arachnids out of her petticoats and stomping on them, in so doing revealing what was, or wasn’t, underneath. The only footage I had to inspire me, however, was one museum-made film on YouTube, which isn’t particularly creative with its choreography to me as a dancer.

When approaching the piece, I first had to consider practical considerations in addition to my own performance capability; music availability (both choice and playing options within the workshop) and restrictions of both time (within the workshop and in my own ability to choreograph and rehearse) and space (within the historic building and workshop space). The initial thought was to choose music by Hungarian composer Franz Liszt, one of the many men that Lola was known to have had a relationship with (she reportedly served as an inspiration for Arthur Conan Doyle’s Irene Adler). Unfortunately, Liszt’s music seemed to match neither the length nor tone I was looking for. Reflecting on Lola as a whole, it seemed to me that my ‘spider dance’ ought to have a flirtatious and stereotypically Hispanic feel. The music from Kitri’s Act IV variation from the ballet Don Quixote seemed to fit the bill for both stereotypical tone, length and accessibility, further supported by the character of Kitri as a feisty young heroine in love.

There was little question that I would not be aiming at imitating the 21st-Century understandings of burlesque or cabaret, for which Lola was arguably one of many forerunners. Conveniently for the ethics of both myself and the museum environment, I settled on being unconvinced by surviving press evidence that Lola certainly revealed a lack of underwear in the piece, having been informed by Stephanie that much of this press was supposedly dominated by the Jesuit order who had publicly criticised Montez since her controversial part in Bavarian politics. With some awareness of 19th Century etiquette, I settled on choreography that blended balletic ‘Spanish’-style movements with a focus on extensions and an acting style which could have been considered evocative by contemporary standards, though tame by modern expectations. For the icing on the cake, Julia arranged for (thankfully artificial) spiders to be both sewn and loose in the netting of my skirts – as I swished the skirts, I was able to quite literally ‘stomp’ on the spiders, a movement made all the more effective by the character shoes. We may not have known quite what the dance looked like in the 1840’s, but both visitors and the Lotherton team alike seemed pleased with the result of my interpretation.

With the Lord Mayor of Leeds (credit: Stephanie Davies).

Choreography aside, the final key challenge was how to best integrate the dance within the afternoon. The Lotherton side envisaged my character entering following the exhibition tour given by my ‘cousin,’ but questions were raised about how to best introduce Lola in a way which would both adequately explain the character and suggest an arc of changing public perceptions. Drawing upon the cousins’ lack of familiarity with one another, we settled on drawing the many parallels that the women shared in music, faith, book-writing, charitable works and lack of success with men. Her showgirl days behind her, Lola turned to giving lectures on ‘The Art of Beauty,’ sharing tips on etiquette and appearance supposedly gleaned from her global tours. Supported by the publication of her book (which also included a series of comical criticisms of the male psyche), Montez became known on both sides of the Atlantic for a slightly less risqué reputation. After several divorces and countless affairs, by her mid-30’s Lola found herself in New York as an all-but penniless recipient of a charity for fallen women, run by an old school friend from her teenage years in Scotland. Seemingly unconvinced by the life she had led, venereal disease contracted decades earlier took her life aged only 39 as a sincere volunteer and penitential Christian. Mirrored by the ups-and-downs of her cousin’s story, this three-dimensional portrait of both women was settled upon as the key storytelling component following the exhibition tour. Delivering a detailed story within a short space of time was challenging from my perspective, but all seemed to be well-received. The workshop following went well after a little persuasion and the Lord Mayor kindly presented us with badges to mark his visit.

A practical experiment in negotiating truth and fiction in a blend of past and present, the experience has encouraged me in many ways in my own research - having long wanted to explore costume and choreography as part of public history, the project was a fantastic opportunity for reflection upon my own praxis as a public historian in training. I hope to talk at greater length with fellow volunteers about their experience of not only attending but performing their own historical characters in other workshop afternoons. The community exhibition programme has been designed to amplify the value of heritage volunteers and the diverse experience they can bring to sharing and changing public understandings of the past. Above all, the afternoon was seen as a great success by the Lotherton team and I look forward to future appearances as my own sort of Lola Montez.